By Richard Edwards and Kevin Tan

Two developments are transforming the social sector around the world. The first is the rise of impact investment. Today’s investors care about the good that they are doing, and philanthropies are searching for more sustainable ways to give. Second is the proliferation of data and tools to analyse it. Instead of relying on guesswork and anecdotes, it is now possible to use data to rigorously determine whether a social programme is working.

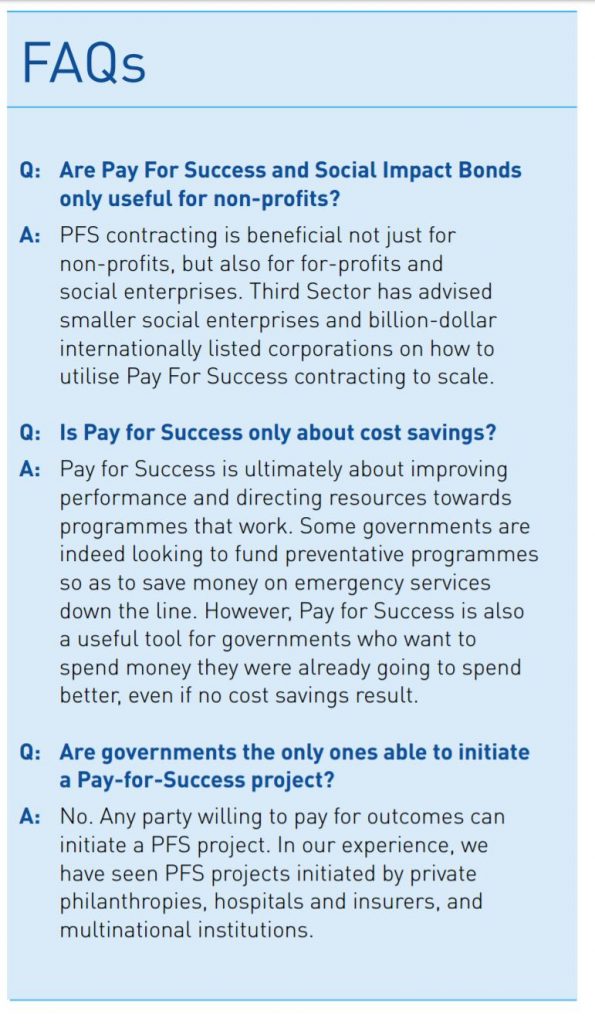

Pay for Success (PFS) and Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) are an exciting tool for governments and philanthropies to combine the use of finance and data to improve outcomes for those most in need. To see why, let us start with an example of a real PFS/SIB project that is currently operating in the US.

In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, USA, youth recidivism is a problem. That is, when juvenile prisoners aged between 18 and 24 finish their sentences, a large percentage of them re-offend. Examining the top 4,000 highest-risk individuals, you would find that 64 per cent return to prison within five years of their release. On average, each individual who goes back to prison costs the Commonwealth US$47,500 a year.

Given that each person who returns to jail does so for 2.3 years on average, this means that the government is paying a total of US$280 million in incarceration expenses just for this group of 4,000 individuals.1 This excludes the social cost, such as lost productive employment opportunities, and the harm to victims of crime. Given the size of the problem, a range of government and philanthropically funded programmes exist to tackle the issue, all of which are well intentioned and deliver innovative interventions. Yet, in spite of the millions of dollars spent a year on these programmes, the needle is not moving on the rate of youth recidivism.

Why is this so? The core problem is that funding is not directed to the programmes that work. There are many potential explanations for this state of affairs, but these three interrelated factors present in many social sectors worldwide are likely to have played a big role:

1. Lack of outcomes data: Long-term outcomes are often not tracked, and when they are, are not shared with providers. In addition, where providers can see the outcomes of the people whom they have treated, they do not know whether those outcomes were due to their work or if some other factor had caused those outcomes. As a result, each provider can only offer anecdotes about their programme’s supposed success, and it is difficult to tell which programme really works.

2. “Frozen recipe funding”: Since government and philanthropy cannot tell which programme has the best outcomes, the norm is to fund those based on some combination of inputs that resemble a recipe. Too often, these recipes are not based on current evidence—at worst, they are based on political preference, and at best, on outdated studies in very different contexts. This ends up funding providers who are focused on conforming to these “recipes” instead of incentivising new ways to improve outcomes.

3. Inability to fund data infrastructure: As funders have difficulty knowing which programmes work, they spread their funding thin between many organisations, resulting in each organisation being underfunded. In addition, one common funding “recipe” is to fund organisations with the lowest level of overheads. The result is that providers find it very difficult to build capacity and invest in infrastructure to track data. In the long run, this perpetuates the cycle of not knowing what works and therefore being unable to fund what works. If this diagnosis is accurate, then the solution is to find a way to rigorously evaluate organisations and direct funding towards the ones that work. A PFS contract is one way to do this—and SIBs can circumvent some issues inherent in PFS contracting.

Pay-for-Success Contracting

PFS refers to an outcomes-based contract. That is, instead of the current “cash-upfront” method by which most social service organisations are funded, a PFS contract is “cash-on-delivery”. Crucially, what is “delivered” in a PFS contract is an “outcome”— something that we really want—rather than inputs that may or may not lead to those outcomes.

In Massachusetts, most providers of services tackling recidivism were being reimbursed on a cost reimbursement or per-person-served basis. With Pay-for-Success contracting, the government is now able to pay only for the number of jail days that a provider actually helps a participant avoid. To accurately calculate the impact of the programme, the government would track the results of participants over four years against a similar comparison group. Doing this kind of tracking at a reasonable cost has only become possible recently, due in large part to the increasing amounts of data, new statistical techniques and cheap computation.

The Role of Social Impact Bonds

What then is the role of a Social Impact Bond? In short, PFS contracts create a cashflow and risk issue for service providers. “Cash-on-delivery” might be permissible for a billion-dollar organisation, but many smaller service providers cannot afford to provide services upfront in the hopes of getting repaid down the line, especially when multiple factors outside of their control can affect that repayment (e.g. policy changes, government transition, and so on). To solve these issues, third-party funders can play an important role in offering bridge financing while the results of a programme are being observed, and in absorbing some of the financial risk should the programme not work.

In Massachusetts, Third Sector Capital Partners, Inc. raised US$16 million from a variety of third-party funders to help an especially promising service provider called Roca expand its services. Roca has 20 years of experience providing intensive services for very high-risk youth. The terms of the project were this: for each day in jail avoided amongst individuals in the project’s treatment group versus those in a comparison group, the Commonwealth would make success payments to repay third-party funders. If Roca hit its targets to reduce recidivism, funders would get their money back plus a small return. Funders included the impact investing arms of commercial banks such as Goldman Sachs, philanthropic aggregators such as Living Cities, and national foundations that wanted their grants returned should the programme succeed. Thus, the rise of impact investors and philanthropies looking to offer loans has been another enabling factor in the creation of Social Impact Bonds.

Let us pause for a second to take stock of what happens as a result of the PFS/SIB structure. In the short run, programming improves because service providers are given the freedom to innovate. If the programmes work, funders get repaid, and can direct their capital towards another high-performing intervention, functioning like a catalyst. This means that in the long run, the nozzle of government and philanthropic funding will be focused on the highest performing organisations, allowing them to scale. With incentives and capital aligned to drive performance, we should expect greatly improved services for those in need.

Now that we have described the overall principle of PFS/SIBs, we will examine how a they actually function in more detail.

The Mechanics of PFS/SIBs

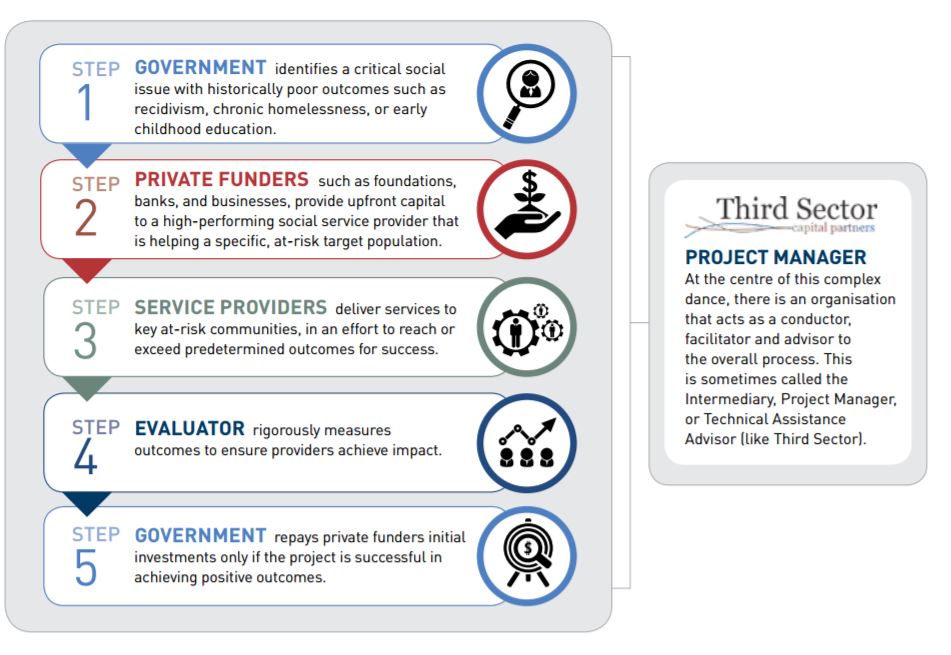

One useful analogy to describe PFS/SIBs is a “line dance”. The main dancers are: 1) an outcomes payer who decides what outcomes to pay for; 2) a set of private funders who provide upfront financing; 3) a service provider who uses the upfront financing to deliver services; and 4) an evaluator who measures results. This is how the dance looks step by step:

These stakeholders are not used to dancing together. Few other initiatives require policymakers, financiers, non-profits and academics to collaborate in such close fashion. As a result, the first time the “music” comes on, there is usually confusion. Third Sector plays the role of “dance instructor”, bringing these different stakeholders together and coaching each through the moves. In due course, everyone is synchronised and moves to the same beat. While this is complex, there are good reasons to believe that PFS and SIBs are worth doing in Singapore.

The Value of PFS/SIBs for Singapore

PFS/SIBs have been growing quickly. The first PFS/SIB was launched in the UK in 2010. By 2012, there were 12 launched projects, growing to 44 worldwide by 2015.2 PFS/SIB projects are now being explored in varied jurisdictions from the US to Australia to tackle issue areas as diverse as early childhood education, healthcare and recidivism.

The Singaporean context differs in important ways. For example, Singapore faces less immediate budgetary constraints than governments of other developed nations, and the Singapore government provides many social services in-house. However, the country’s unique status as a financial hub and its “Smart Nation” push may mean that PFS/SIBs could be particularly beneficial. Chiefly, these benefits could include:

1. Accelerating development of a performance-driven social sector: There are hundreds of social sector organisations in Singapore. The National Council of Social Service (NCSS) is the main coordinator of local Voluntary Welfare Organisations (VWOs), and had 443 VWO members in 2014.3 PFS/SIB contracting can be used to further enable the development of these organisations to deliver long-term outcomes.

2. Driving government resources to innovations that work: NCSS disbursed S$242 million to VWOs in 2014. Beyond VWOs, the Singapore government also deploys millions of dollars in delivering healthcare, prisons and other socially beneficial services. By specifying outcome targets rather than inputs, PFS/SIBs can help the government steward taxpayer resources for maximum effect by directing them to the best interventions.

3. Increasing impact of philanthropic dollars: Singapore’s philanthropic sector is growing in size. In 2014, individuals donated a total of S$1.25 billion to philanthropy, a 14 per cent rise from 2012.4 A SIB can help philanthropists maximise their impact in the short run by leveraging commercial capital to make a bigger impact: each philanthropic dollar committed in a SIB is often accompanied by capital from sources, such as commercial banks, that would not have invested otherwise. Furthermore, funders stand to get their capital back if the intervention succeeds. This allows for the same philanthropic funding to be deployed multiple times towards high-performing organisations.

4. Building Singapore as a regional hub for non-profits and impact investment: Singapore is at the centre of an exciting growth region of the world, and SIBs could position it as a leader in the social sector and impact investing field. First, SIBs could be used to enhance the capabilities of local organisations with best practices of the social sector worldwide. Given its strong regional brand, this could eventually be another “export” area for Singapore. Second, SIBs could also jumpstart the product market for impact investments and further increase the sophistication of the philanthropic ecosystem. Third, SIBs will additionally help create demand for impact evaluation and specialised legal services— both potential growth areas in Singapore’s service industry portfolio. Ultimately, PFS/SIBs are an exciting tool to stimulate innovation and the creation of a performance-based ecosystem. The key is to find the correct area to apply this tool.

Potential Issue Areas for Singaporean PFS/SIBs

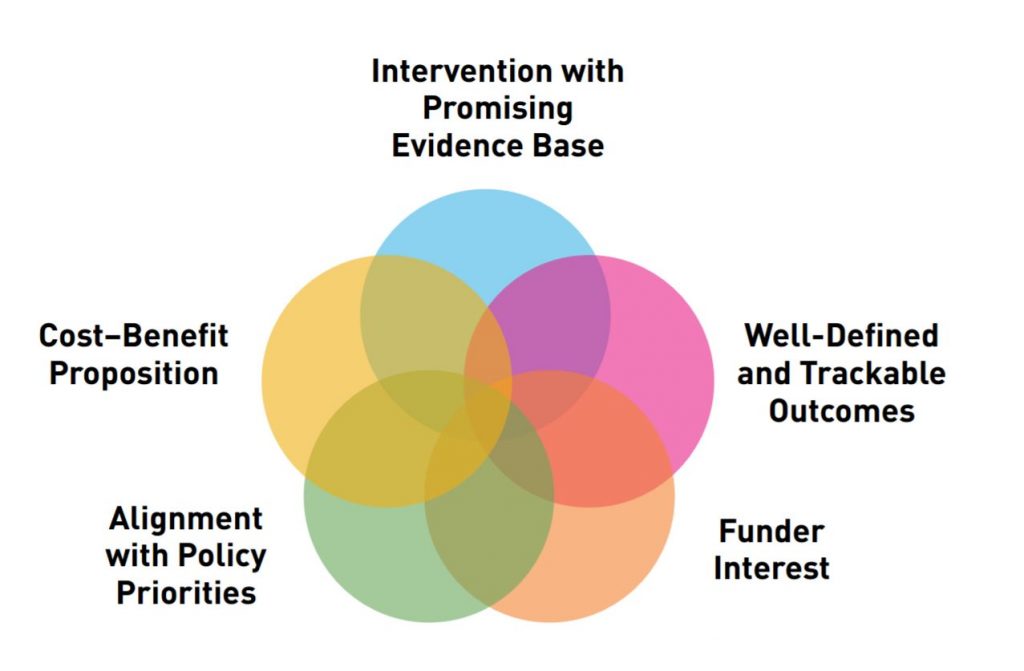

A successful SIB requires several key pieces to be in place: an intervention with a promising evidence base; a solid cost-benefit proposition; well-defined and measurable outcomes; funder interest; and coherence with the existing policy landscape.

The process of determining whether these pieces exist to a sufficient degree in any given issue area in order to construct a SIB requires intensive diligence work over several months—what we call a “Feasibility Study”. However, it is possible to quickly filter out which interventions are non-starters and to zoom in on which issue areas are worth further investigation. In this vein, Third Sector has had ongoing conversations with Singaporean stakeholders in the government, non-profit, and funder arenas. Our research indicates that the following issue areas may be worth investigating further for a SIB.

Diabetes Diagnosis and Management

The NUS School of Public Health estimates that the annual cost of diabetes in Singapore was US$787 million in 2010. By 2050, this cost will increase to US$1.8 billion and there will be one million diabetics, potentially leading to an over-burdening of the healthcare system.5 In Israel, a SIB is already underway to help individuals who are very likely to develop diabetes—“pre-diabetics”—not succumb to the disease. In Singapore, our discussions indicate that a SIB could be valuable in two related angles: diagnosing undiagnosed diabetics, and in managing the health outcomes of diagnosed diabetics. Third Sector is currently working with a promising provider in the US that helps diabetics manage their diets. The positive outcomes we hope to see from their intervention are a decrease in patients’ blood sugar levels and a reduction in emergency hospitalisation events. What would make this or a similar programme promising for a SIB in Singapore is that the outcomes are objective and can be measured in a reasonable timeframe. The intervention is also cheap relative to the high cost of hospitalisation. With the recent launch of the “War on Diabetes” and the Diabetes Prevention and Care Taskforce, this is clearly a priority issue area for the Singapore government.

Exercising to Prevent Elderly Falls

International trials have shown that resistance and balance training for the elderly has a significant positive effect on health outcomes, in particular a reduction in the rate of dangerous falls. A SIB would be an effective way of taking this promising intervention to scale, improving the health of the elderly, and reducing healthcare costs resulting from falls.

A key advantage of this programme is the presence of a clear outcome metric (elderly falls) that can be rigorously measured and on which there is an evidence base. The prevention of elderly falls can lead to significant benefits. Elderly falls often lead to serious injury, hospitalisation, the need for a caretaker, and the cost/lost productivity related to that caretaker. The Lien Foundation is currently implementing a multi-site pilot of Gym Tonic, a specialised gym programme for seniors.6 Should this show promising results, the track record could be built upon to attract funders for a SIB.

Reducing Youth Recidivism

An average of 1,600 juveniles (aged between 7 and 16 years) were arrested each year from 2008 to 2014.7 A SIB could deploy several proven evidence-based therapies that could break this cycle, thereby helping youth turn their lives around, reduce incarceration costs, and increase the number of productively employed members of society. While local service delivery organisations may not be currently delivering these evidence-based therapies (e.g. Moral Reconation Therapy), training and certification to do so can be obtained for a reasonable cost abroad. A SIB could hence be a capacity-building opportunity for local organisations.

Many jurisdictions have started with SIBs targeting recidivism (e.g. Massachusetts in the US). This is because involving recidivism is extremely high (involving the police, courts, jail, lost productivity, harm to victims), and the effects of a successful programme can be measured in a very short timeframe. Helping Abused Children and Youth Graduate from the Residential Care System There are presently 22 Children and Young Persons Homes providing residential care programmes for children and youth in Singapore who suffer from family violence, abuse or neglect.8 A SIB could help these abused children and youth graduate from the residential care system by providing them with foster homes. It could even help these children leave the foster system altogether by providing the necessary services to reunite them with their families.

In Cuyahoha County, Ohio, USA, Third Sector is implementing a SIB that reunites children in foster care with their mothers. The programme concentrates on stabilising the family’s home environment using a mixture of trauma reduction therapy and transition therapy, with the aim to significantly reduce the number of days a child spends away from his or her family. Research has shown that this leads to better outcomes for the child, and it also helps the government free up scarce foster care slots for other children who may be unable to reunite with their families.

Helping to Improve the Skills of the Unemployed/ Underemployed

Skills are a big concern of the Singapore government, with the Committee on the Future Economy underway. A SIB could help spur innovation in the types of programmes, and direct government funding towards the best programmes. What is most intriguing about this particular area is the ability to help funding—that was already going to be spent—be deployed for the greatest possible impact. In the US, Third Sector is helping the federal government conduct five different Feasibility Studies to better direct existing spending on their US$870 million per year youth workforce programming.9 A Singapore SIB in this area could focus on a different age group if more appropriate.

This list is by no means exhaustive. Many areas where significant social benefits can be captured might be amenable to a SIB: the US has looked at providing pre-natal care; Israel is looking into SIBs to tackle highly unique areas such as ultra-orthodox employment; and some African countries are looking at malaria. The key is to conduct a rigorous study to ensure that the success factors for a SIB are in place before constructing a project.

Challenges to PFS/SIBs

SIBs are a promising means to the end of outcomesoriented service contracting. In our experience, there are several challenges that stakeholders must tackle when creating a SIB.

SIBs Are Complex: A SIB has many moving parts, and requires the cooperation of a range of stakeholders from very different fields. Project stakeholders must understand risks such as operations, payment and referrals. However, as more projects are implemented, we are seeing more opportunities for “templatisation” around common issue areas, as well as a shortening of project development timing as project parties become more sophisticated. At Third Sector, our first project (Commonwealth of Massachusetts) took three years to turn from idea to reality. We consciously created a learning community around this major Pay-for-Success project and ensured that all project parties shared lessons learned. We have managed to reduce that time with each one of our projects since, through a combination of prior experience, tight project management, and simplifying the essential components of a SIB.

Transaction Costs Are High: The SIB mechanism can require a substantial amount of ancillary expertise. An intermediary is needed to put the project together: a lawyer to draft the contracts; an independent evaluator to measure the results; and a programme manager to ensure that the project is on track. These add costs beyond those of service delivery. The key question that the outcomes funder should ask is whether these additional transaction costs are worth the benefits—in the short run of only spending money if the programme works; and in the long run to create a performance-driven ecosystem. In most cases, the answer is yes. After one catalyst SIB project imbeds valuable knowledge and process, governments are able to continue outcomes-oriented innovation without the need for the SIB architecture. Third Sector has put together full projects much smaller than Massachusetts, of about a US$4–5 million upfront raise size. Elsewhere in the world, upfront raises of "pilot SIBs" have been even smaller: in Canada, a SIB was launched with US$900,000; US$320,000 in Belgium; and US$150,000 in Portugal.

The Need for a Committed Champion

SIBs can represent a profound change from business as usual. Many SIBs also face a “wrong-pocket problem”—that is, benefits accrue across many different government agencies or other parties, resulting in no single party being willing to sponsor a SIB. In the many jurisdictions where we have worked, the number one differentiator between a successful and unsuccessful SIB is the presence of a forward-thinking champion who can unify the success payers and drive the project forward. The internal skill of working across departments, thinking early about the need for resources, research and funding are critical for a champion.

Given these challenges, one should always honestly ask if the use of SIBs in financing is necessary to achieve PFS contracting. SIBs are not always the right choice for a jurisdiction. The distinction between a Pay-for-Success contract and the type of upfront financing used to achieve it is critical—it is possible to have a PFS contract without a SIB.

PFS Beyond SIBs

Having spent some time delving into SIBs, let us regoup and remember the objective of PFS contracting and of SIB financing. The end goal of PFS is to direct resources towards what works for those in need. SIBs are one way to enable PFS contracting by overcoming cashflow and risk issues for the service provider. But it is not the only way. There is yet other example of an innovative financing mechanism, which can help achieve the goals of PFS.

PFS contracting generates cashflow and risk issues for the service provider if the payer withholds payment until outcomes are seen. From a payer’s perspective, the advantage of withholding payment is twofold: first, it only spends money if the programme works; and second, it can reap the benefits of the programme now while only paying later. In short, it is similar to a two-in-one package of a “money-back guarantee” and a “layaway” plan.

However, not all governments need the two-in-one package. For payers who would like to have a money-back guarantee but who do not need the layaway plan, a Social Impact Guarantee (SIG) may be more suitable than a SIB. =

Social Impact Guarantee

Here’s an overview of how a SIG works:

• The government/philanthropic payer funds a given social programme upfront, just like it currently does

• At the same time, it purchases a “money-back guarantee” insurance policy from willing insurers

• The programme is delivered and its outcomes are evaluated

• If the programme is successful, no payout occurs from insurers to the government/philanthropy

• If the programme is unsuccessful, however, insurers repay the government/philanthropy for the cost of services

• At the end of the day, the government/philanthropy will have only paid out if a programme works, thus accomplishing the aim of PFS contracting

The great advantage of the SIG is that it can be easily applied to existing spending. A government or philanthropy can take out this kind of “money-back guarantee” on any of its current spending. Third Sector is currently working to implement SIGs in several jurisdictions in the US.10

There are many other ways to achieve the goals of PFS, but an initial study is important to help figure out whether a SIB, SIG, or some other tool works best in each particular context. There is much innovation left to do in this area that can help address the pressing problems of those in need.

Next Steps

Taking PFS from idea to launch requires commitment from multiple stakeholders and considerable process expertise. Our initial exploration has led us to believe that many critical ingredients for a SIB in Singapore are already in place. Two concrete “next steps” are needed to bring this exciting innovation to fruition in Singapore.

Commission a PFS Feasibility Study: To launch a PFS project, it is necessary to find a capable service provider, define outcomes, build data systems and structure upfront finances. We have seen in other jurisdictions that a PFS Feasibility Study can be an important jumpstart in refining how a PFS project should be executed, and in bringing the right parties to the table. We often find the process of doing this study helpful in and of itself, whether or not it leads to a project—ultimately, outcome payers, investors and service providers learn to coordinate the outcomes they are trying to achieve, gain a better understanding of the population they are trying to serve, and learn more about best practices in delivering services.

Sponsor Successful Outcomes in a PFS Project: Both the government and private philanthropy can play the role of outcome payer for a PFS project. By only paying for successful outcomes, sponsoring a PFS project allows for every dollar to achieve a clear “bangfor-buck” in impact and innovation. Our experience has taught us that identifying a committed and innovative outcomes sponsor is indispensable for project success. Private philanthropy can take the lead in sponsoring a pilot PFS project to convince the government that this type of innovative structure is feasible. For example, in the State of Utah, USA, a group of private philanthropic donors promised to pay for the outcomes of one year of a PFS project for a high-quality kindergarten. The government subsequently sponsored three more years.

Notes

1 A case study of the project with more details can be found here: “Preparing for a Pay For Success Opportunity”. http://www.thirdsectorcap.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/ Third-Sector_Roca_Preparing-for-Pay-for-Success-in-MA1.pdf

2 Brookings Institute, “The Potential and Limitations of Impact Bonds”. http://www. brookings.edu/~/media/Research/Files/Reports/2015/07/social-impact-bonds-potentiallimitations/Impact-Bondsweb.pdf?la=en

3 National Council of Social Services, NCSS Annual Report 2014. https://www.ncss.gov.sg/NCSS/ media/NCSS-Publications/NationalCouncilofSocialServiceAnnualReportFY2014(1).pdf

4 National Volunteer and Philanthropy Center Individual Giving Survey 2014. http://knowledge.nvpc.org.sg/individual-giving-survey-2014-2

5 For estimated costs of diabetics, see May Ee Png, Joanne Yoong, Thao Phuong Phan and Hwee Lin Wee, “Current and Future Economic Burden of Diabetes among Working-Age Adults in Asia: Conservative Estimates for Singapore from 2010–2050”, BMC Public Health 16, 1 (2016). doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2827-1

6 Gym Tonic’s website and press release contain more details of the pilot and evidence base. http://www.gymtonic.sg; http://lienfoundation.org/sites/default/files/Gym%20 Tonic%20Press%20Kit%20Complete.pdf

7 Ministry of Social and Family Development, “Juvenile Delinquents: Juveniles Arrested”, 2015. http://app.msf.gov.sg/Research-Room/Research-Statistics/JuvenileDelinquents-Juveniles-Arrested

8 Ministry of Social and Family Development, “Children and Young Persons Homes”, 2014. http://app.msf.gov.sg/Policies/Strong-and-Stable-Families/Nurturing-Protectingthe-Young/Child-Protection-Welfare/Children-and-Young-Persons-Homes

9 Third Sector is conducting these services as part of a federal Social Innovation Fund grant. http://www.thirdsectorcap.org/sifcohort2

10 George Overholser, “An Alternative to the Social Impact Bond?”. http://www. thirdsectorcap.org/blog/social-impact-guarantee written by Richard Edwards, Kevin Tan

Richard Edwards is Partner, Capital Markets, at Third Sector. He has led project and business development efforts for investment banking, insurance brokerage and entrepreneurial businesses for over 20 years. As the former Global Head of Project Finance and Advisory for JP Morgan Chase based out of Singapore, he has extensive global experience in structuring and syndicating funding for projects in the private and public sectors. Rick has a particular passion for working on child abuse prevention. He has been President and/or board member of numerous civic organisations, including the Exchange Club Foundation, Pilgrim Towers Housing, and the Parenting Skills Center. He can be reached at redwards@thirdsectorcap.org

Kevin Tan is a Singaporean based at Third Sector’s Boston office. He is the project lead for several Pay for Success strategic advisory, feasibility assessment, and project construction engagements across the US. Prior to Third Sector, he spent time working on Social Impact Bonds in Israel and did his graduate work with the National Council of Social Service on implementing Social Impact Bonds in Singapore. Kevin graduated with an MPP from the Harvard Kennedy School and from the University of Oxford with FirstClass Honours in Philosophy, Politics and Economics. He can be reached at ktan@thirdsectorcap.org

Third Sector Capital Partners Third Sector leads governments, high-performing non-profits, and private funders in building evidencebased initiatives that address society’s most persistent challenges. As experts in innovative public–private contracting and financing strategies, Third Sector is an architect and builder of the United States’ most promising Pay-for-Success projects, including those in Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and Santa Clara County, California. These projects are rewriting the book on how governments contract for social services: funding programmes that work to measurably improve the lives of people most in need while saving taxpayer dollars. A 501(c)(3) non-profit based in Boston, San Francisco, and Washington DC, Third Sector is supported through philanthropic and government sources, including a grant from the Corporation for National and Community Service’s Social Innovation Fund.

Comments