By Rashika Ranchan

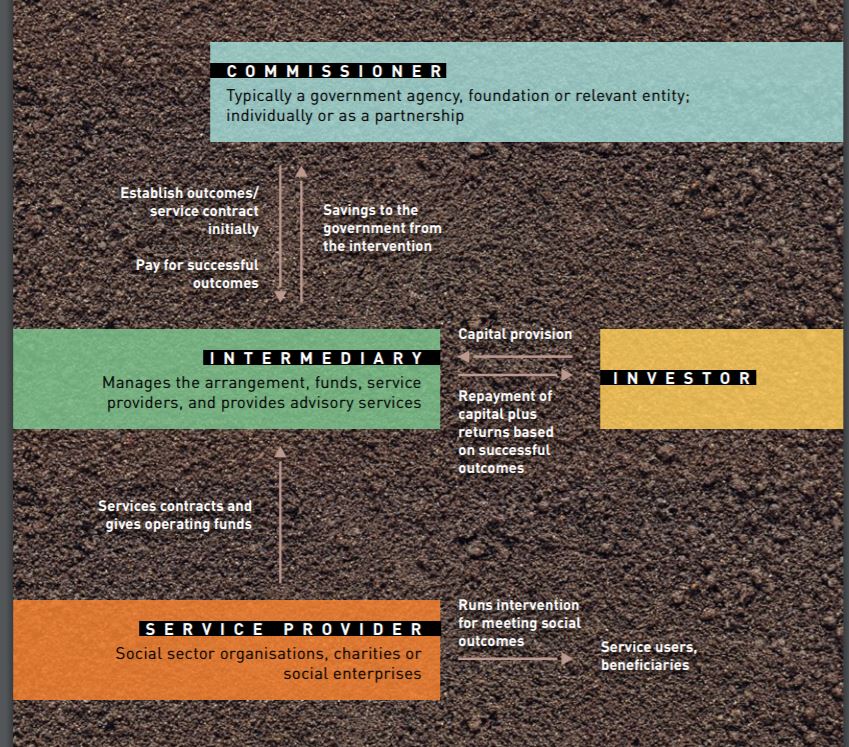

In a landscape of rising social needs, coupled with an uncertain economic climate, Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) offer an exciting opportunity to test innovative models of impact within social service provision. With the shrinking of global public spending, SIBs enable the public sector to commission preventative services, and help tackle deep-rooted social problems. SIBs bring together a partnership of commissioners, investors and service providers to resolve intractable social issues. In this financial mechanism, investors pay for an intervention at the beginning to improve social outcomes. These social outcomes are pre-defined, and the intervention—if effective—should result in public sector savings and wider benefits to society. The commissioner makes returns to investors only when the specified outcomes are achieved. \

When the world’s first SIB—the Peterborough Social Impact Bond—launched in the UK in 2010, it was heralded as a groundbreaking intervention. It funded rehabilitation services for short-sentence prisoners released from prison, with the aim of reducing post-release re-offences. The UK Ministry of Justice, supported by the Big Lottery Fund, entered into an agreement to pay a return to investors if targets for reducing reconvictions were achieved.

The space for social investment, which blends social and financial returns, has grown over the past few years: it supports investment in charities and social enterprises to tackle social issues—and is also significant in promoting models like SIBs.

The launch of Big Society Capital in UK in 2012, as the first-of-its-kind social investment wholesaler in the world, brought about greater momentum to this impact investing space. By blending entrepreneurship, social investment and public funding, SIBs are a pioneering way to achieve social impact. They illustrate the impetus to rethink public service delivery through innovative financial mechanisms.

Now more than six years after the launch of the Peterborough SIB, social impact bonds continue to garner the interest of many policymakers, academics and practitioners worldwide.

Globally, there are over 50 SIBs that have been developed, with the UK accounting for around half of these, followed by the US. Many commissioners and investors across various countries have shown interest in the potential of SIBs, including the Netherlands, South Korea and Australia. To date, SIBs aim to improve services that focus on various social issues, including: children in care, young people not in education, employment or training, adoption, homelessness, and reoffending. Presently, there is interest to nd out if SIBs are really working. However, it is still early days for their evaluation, and most SIBs do not yet have a proven “track record” to speak of. However, while there has been some scepticism over what really “works”, some early successes or progress have been reported. For instance, one of the initial SIBs to tackle youth unemployment, delivered by the London-based youth charity ThinkForward, has reported generating a return for investors. It has demonstrated that engaging early with disadvantaged young people can both improve the lives and opportunities of these youth, and provide savings to the public purse.

Implications for Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, too, there is growing recognition of the need to look at models beyond traditional grantmaking. A stronger social enterprise and impact investment space will harness greater innovation, thereby encouraging the emergence of new models like SIBs. Although this space within the region is relatively nascent, the appetite is on the rise. For example, in Singapore, support for the social enterprise sector has been stepped up over the past few years. In 2015, raiSE (Singapore Centre for Social Enterprise) was set up as a one-stop centre—supported by the Ministry of Social and Family Development, Tote Board, National Council of Social Service and Social Enterprise Association—to increase support for and promote awareness of social enterprises in Singapore.

However, although the social sector is getting more experimental, it is fragmented and diverse. Raising funds for innovation thus remains a challenge. Additionally, services that are centred on prevention are harder to fund. Even if budgets were available, public services are typically designed to meet more remedial rather than preventative needs. A thin evidence base can lead to significant delivery risk for preventative programmes. SIBs can therefore create pathways to harness private or non-governmental capital for innovation and preventative services. Alongside the social policy domains like juvenile delinquency, homelessness and workforce development, SIBs can also be considered for social issues that are on the rise, including ageing and mental health. In developing economies, areas such as education, health and poverty alleviation are expected to become more prominent. SIBs can thus be developed for specific social needs according to the country’s focus.

A key impetus in developing SIBs is the progress towards social outcomes. Rather than focusing on inputs or outputs, SIBs are based on achieving social outcomes to better support the most vulnerable sections of society. Although many grant-makers are moving towards outcomes-based funding, non-profits still struggle to embed an outcomes approach fully within their services. Further, traditional funding continues to rely on delivering a set of services and outputs rather than demonstrating measurable outcomes. This means that there is limited incentive to innovate. SIBs contrast with traditional funding in this regard. The focus on outcomes supports greater accountability and transparency of public funds. Greater rigour in performance management and evaluation also contribute towards building a broader evidence base for what works. In addition to savings to the public purse, the real cost of a social problem can be better analysed and a stronger case can be made for mainstreaming the intervention. Through models like SIBs, the capability of the social sector within the area of impact measurement can be built over time.

Another fascinating aspect of SIBs is “collaboration”. For the region of Southeast Asia, SIBs will help build a “new social compact” between public-sector funders, service providers, investors and philanthropists. It can, indeed, be a win-win for all parties involved: for public sector commissioners, SIBs enable the influx of private capital to fund preventative action on complex and expensive social problems; for the non-profit sector, they offer additional and diversified sources of funding to innovate; and for the investors, SIBs provide both financial and social returns.

This potential to create a multiplier effect by a shared value to the “public, private and people” sectors is compelling. The Essex SIB in the UK—an intervention to prevent youth aged between 11 and 17 years from entering care or custody, and safely remain with their families—is one such partnership that brings together a range parties: investors (Big Society Capital, Bridges Ventures Social Entrepreneurs Fund, King Baudouin Foundation, The Tudor Trust, Barrow Cadbury Trust, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and Ananda Ventures [Social Venture Fund]); outcome payer (Essex County Council); delivery organisation (Action for Children); and manager (Social Finance Ltd).

While there are clear benefits to SIBs, there is still much to learn about how best to structure them and their added value as opposed to a simple funding arrangement. Some issues need to be considered carefully before developing a SIB.

First, SIBs are not relevant for all types of social projects. It can be successful only in areas where outcomes can be measured and where it is possible to monetise savings from a social intervention. The cashable savings must outweigh the higher cost of capital and the considerable set-up costs. Further, there is a strong need to understand the dynamics of the market, including: identifying the right issue, beneficiary group, bringing rigour in data, and monetising it. At present, many social projects continue to require more traditional forms of funding.

Ecosystem Building

In conclusion, there is no one- size-fits-all approach when it comes to SIBs. While the core principles of SIBs remain consistent across geographies, different commissioning practices and structuring can be adopted to suit a country’s local needs. SIBs can be piloted for a certain social issue, to better understand the impact before scale-up and wider implementation. As we move towards embracing more innovation and entrepreneurship, there is scope for replication of good practices across the region. With funders looking to achieve greater impact from their funding, this can be done through strategic grant-making that builds into the mix evidence-based funding, outcomes, impact measurement and capacity-building, or—where appropriate—through experimentation with various funding models like SIBs. It is also possible to adapt models like SIBs and venture philanthropy to create new and hybrid models of philanthropy and nance, based on the needs of a sector and relevant to a local context.

Comments