By Haneol Jeong, Mitchell Laferriere, John Kinsella, Remi Cordelle, Maaya Murakami, Christian Petroske and Florian Parzhuber

What is social finance? Rachel Kalbfleisch of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) defines it as a collection of approaches to managing money that create value for society or the environment, often while producing a financial return, while the MaRS Centre for Impact Investing calls it “an approach to managing money to solve societal challenges”.

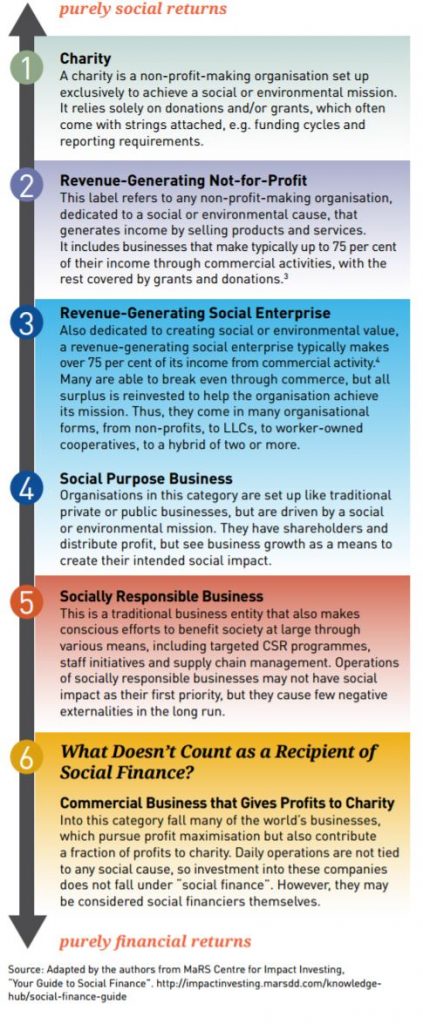

In other words, social finance is a movement that covers various ways of using finance—via socially responsible investments, micro-loans, community investments, and so on—to achieve a social or environmental impact. Who is involved in this process? While charities, socially driven businesses and governments all work towards creating positive social change, those who finance them are the ones facilitating the creation of social and environmental value (hereafter “social value”). These funders are thus considered to be practising social finance.

It’s Complicated: Other Things Also Called “Social Finance”

Social Impact Bonds

Social impact bonds (SIBs), also known as “Pay for Success” financing, are perhaps the most confusing form of social finance. For one, they aren’t really bonds, but complex contracts that are used to pay for large social impact projects. They essentially work like this: investors invest their cash in a social project and evaluate its results. These results are then tallied based on how much money they save the government—for instance, by reducing prison recidivism, the state doesn’t need to pay for as many prisoners as it would’ve had to without the programme. Once the project is completed, the government pays out a portion of the savings to the investors who originally put up the money. Often, these savings are so large that the investors can make returns at or above market rates.

Microfinance

Championed by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, founder of Grameen Bank, microfinance is a way of providing financial services to the working poor at low interest rates so as to increase their incomes and improve their livelihoods. Originally only referring to loans, microfinance has expanded to encompass other services like savings and insurance. Large banks don’t typically provide loans to the poor because they consider it too risky. If they or others do, it’s usually at astronomical interest rates. Microfinance brings interest rates down and often pairs loans with financial literacy training.

Social Finance: Explained Further

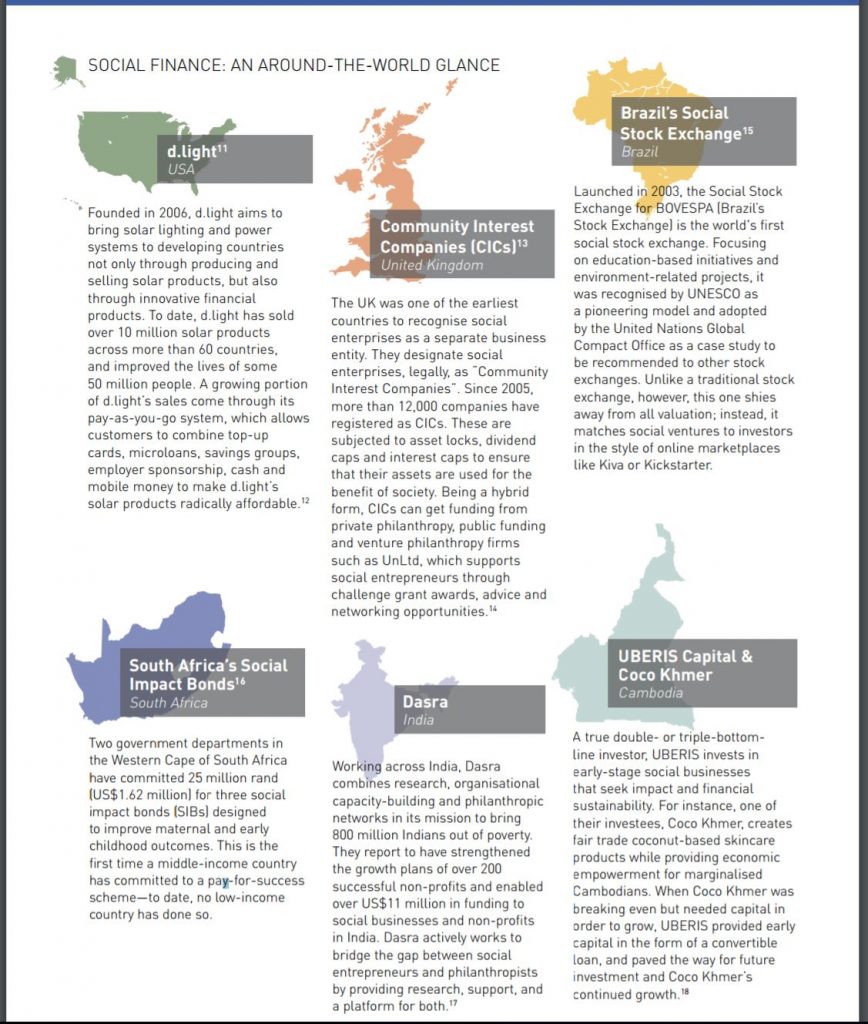

This section covers the relationship between risk, financial returns and social impact; touches briefly on the tricky issue of impact measurement; presents an around-theworld glance at social finance initiatives carried out in various countries; and identifies some of the biggest players in the field of social finance.

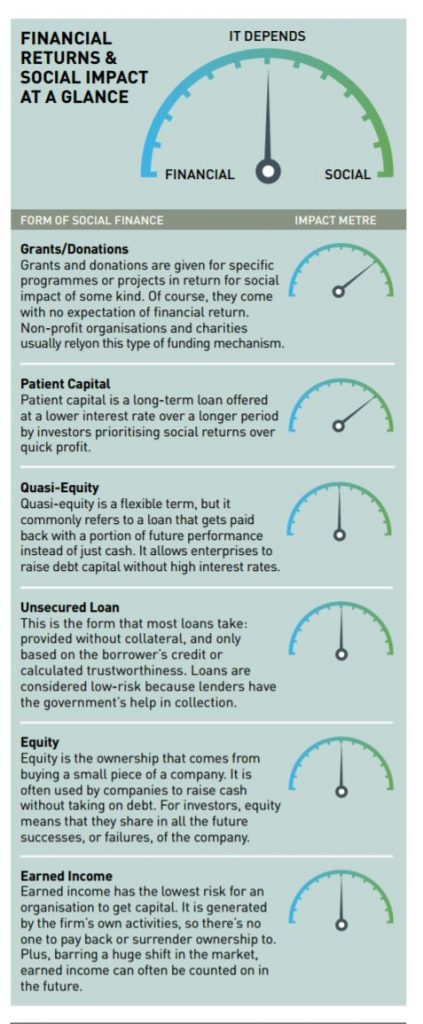

Risky Business?

From the investor’s perspective, risk is defined in terms of how difficult it will be to get one’s money back, with interest, from an investment. The less “risky” and the higher the return, the more investors can be convinced to put up more of their funds. The impact investor, or social financier, looks to achieve positive social value, and often considers the level of social impact that their investment might yield. Different investors use different financial tools, depending on their appetite for risks, financial returns and social impact. The following illustration shows the various levels of financial return and social impact associated with different forms of social finance.

Social Impact: Context Matters

The expected social impact of many types of investment depends on what the recipient does with it. For instance, a company raising capital in the form of equity could use it to expand its low-cost health treatment to new geographies, helping many more low-income people live healthier lives. Another company could also use equity to develop a new technique to drill for fossil fuels. The financial tool is the same, but the social or environmental impact is widely different.

Market-Rate Returns?

Is it possible to achieve both social and financial returns simultaneously? A new analysis conducted by the Cambridge Associates Impact Investing Benchmark, in association with the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), shows that the answer is yes: “market rates of return are achievable through impact investing”, states GIIN CEO Amit Bouri. In this study, the benchmark compared normal venture capital and private equity funds to funds that have both financial and social impact objectives. Overall, the analysis found an internal rate of return (IRR) of 6.9 per cent for impact funds, as compared to 8.1 per cent for non-impact funds—“within spitting distance”, as classified by one commentator. However, breaking down the data reveals an even more compelling story. For instance, impact investing funds in emerging markets posted returns of 9.1 per cent; impact investing funds that were smaller (under US$100 million) saw 9.5 per cent returns; and smaller impact investing funds focused on the US returned a whopping 13.1 per cent. This robust data shows that investors who seek social impact do not have to sacrifice profits, and might even be able to outperform the market in some cases.

Measure for Measure

Almost everyone (with good intentions) hopes to achieve positive social impact. According to Mark Florman, Robyn Klingler-Vidra and Martim Jacinto Facada, “The notion of the social impact of business has become so mainstream that government at the highest levels—including G8 leaders and even the Pope— advocate the creation of institutions to give greater attention to driving social impact”. However, one of the most difficult challenges facing social finance revolves around the question: how do we measure social impact? There are, in fact, many ways to measure it, but the crucial question concerns how to consolidate these many methods under one impact measurement and evaluation system. At present, the impact measurement field is quite chaotic: each institution or region typically has its own assessment criteria for impact, and creates its own metrics. Though in recent decades the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and Social Value UK (formerly the SROI Network) have made efforts to consolidate their metrics, there has not been a single governing authority to establish an official and centralised system of impact measurement and evaluation.

There are, in fact, many ways to measure it [social impact], but the crucial question concerns how to consolidate these many methods under one impact measurement and evaluation system.

Triple Bottom Line (People, Planet, Profit)

The triple bottom line is one way to think about what an organisation’s relationship to its impact should be. The triple bottom line consists of three Ps: people, planet and profit. Organisations that take this approach are understood to prioritise social, environmental and financial impact equally in order to take into account the full costs of operating their business.

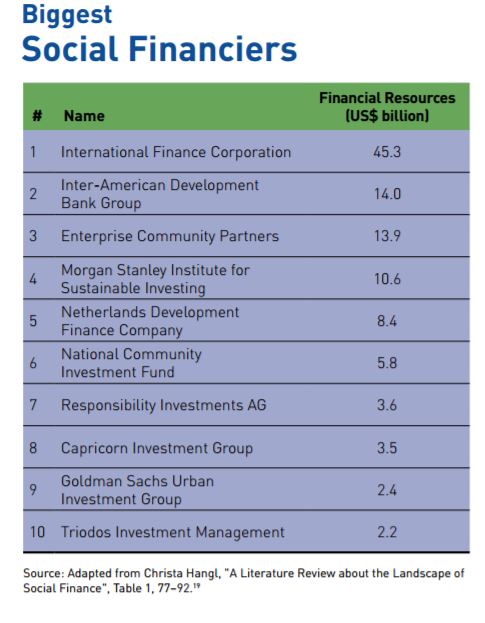

The International Finance Corporation

Founded in 1956, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) is the private investment branch of the World Bank. Over US$45 billion in investments from the IFC go towards loans and venture capital. In turn, most of its funding comes from issuing triple-A rated bonds in several different capital markets. Most of its bonds are of the traditional variety, marking investments that lack an exceptional focus on social impact. However, certain innovative themed bonds such as Green Bonds, Banking on Women Bonds, and Local Currency Bonds also allow investors to target causes and communities they want to support. The reach and financial power of the organisation is impressive: a Google search for “IFC” will typically yield headlines such as “IFC plans to invest $75 million in Glenmark Pharmaceuticals”; “IFC to invest $15 million in Vietnamese animal feed firm Anova’s Bond”; or “IFC to invest $20 million in Abraaj Group”.

The IFC example foregrounds the complexity of drawing hard-and-fast boundaries around the field of social finance. Even though many of the IFC’s investments are in private-sector businesses and multinational corporations (i.e. investments that are not particularly “social”), its ultimate mission is a social one: to create jobs and seed economic growth in order to advance development.'

Going forward, social finance faces a broad set of opportunities and challenges. Ellie Howard of Cicero Group suggests that “in time, social finance will become inherent to the practice of investing in line with the progression to a conscious economy”, but that “the sector first needs to establish itself”.21 In other words, what is now somewhat of a fringe concept—investing to achieve measurable social impact—will eventually become inextricable from “plain-old” normal investing. When that happens, we’ll have an economy that includes social impact in its core calculus; that incorporates more of the full costs and benefits of doing business; and that is more “conscious” of the impacts it has. Howard goes on to call for “the creation of a platform to not only attract the investment, but also the brightest minds and expertise for the sector to flourish”.22 The table below presents a summary of the prospects and obstacles facing social finance, and its potential to thrive.

Now that we’ve examined the kinds of organisations that receive social finance, discussed the financial tools used, cited examples from around the world, and highlighted some exciting opportunities ahead, we hope this “SoFi 101” has covered some important ground, albeit not exhaustively, on the topic of social finance. Maybe the next time someone asks, “What is social finance anyway?”, this article can be a place to start.

Notes

1 Rachel Kalbfleisch, “Social Finance Week: Social Finance 101”, Charity Village. https://charityvillage.com/Content.aspx?topic=Social_ Finance_101#.V5cCl2R97u2

2 MaRs Centre for Impact Investing, “Your Guide to Social Finance”. http://impactinvesting.marsdd.com/knowledge-hub/social-financeguide

3 Eva Varga and Malcolm Hayday, A Recipe Book for Social Finance (Brussels: European Commission, 2016). http://ec.europa.eu/social/ main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=7878

4 Ibid.

5 Investopedia, “Risk Definition”. http://www.investopedia.com/ terms/r/risk.asp

6 Cambridge Associates and Global Impact Investing Network, “Private Impact Investing Funds Yielded Financial Performance in Line with Similar Private Investment Funds with No Social Objective, According to New Impact Investing Benchmark”, Thegiin. org, 25 June 2015. https://thegiin.org/assets/Benchmark%20PR.pdf

7 Anne Field, “New Study: Impact Investors Don’t Have to Sacrifice Financial Returns”, Forbes, 26 June 2015. http://www.forbes.com/ sites/annefield/2015/06/26/new-study-impact-investors-dont-haveto-sacrifice-financial-returns/#3c33ebe66853

8 Cambridge Associates and Global Impact Investing Network, “Introducing the Impact Investing Benchmark”, 25 June 2015. https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/Introducing_the_Impact_ Investing_Benchmark.pdf

9 Adapted from Mark Florman, Robyn Klingler-Vidra, and Martim Jacinto Facada, “A Critical Evaluation of Social Impact Assessment Methodologies and a Call to Measure Economic and Social Impact Holistically through the External Rate of Return Platform”, LSE Enterprise Working Paper #1602 (February 2016). http://www.lse. ac.uk/businessAndConsultancy/LSEConsulting/pdf/Assessing-socialimpact-assessment-methods-report.pdf

10 The Economist, “Triple Bottom Line”, Economist.com, 17 November 2009. http://www.economist.com/node/14301663

11 Shell Foundation, “D.light Launches $5 Solar Lantern”. http://www. shellfoundation.org/Our-News/News-Archive/d-light-Launches-$5- Solar-Lantern

12 Esha Chhabra, “Bite-Size Payments Go Global: Solar’s Next Challenge”, Forbes, 12 August 2014. http://www.forbes.com/sites/ eshachhabra/2014/08/12/bite-size-payments-go-global-solars-nextchallenge/#13c490d773fe

13 CIC Association, “What Is a CIC?”. http://www.cicassociation.org.uk/ about/what-is-a-cic

14 UnLtd UK, “About UnLtd”. https://unltd.org.uk/about_unltd

15 Chhichhia Bandini, “The Rise of Social Stock Exchanges”, Stanford Social Innovation Review, 8 January 2015. http://ssir.org/articles/ entry/the_rise_of_social_stock_exchanges

16 Sophie Gardiner and Emily Gustafsson-Wright, “South Africa is the First Middle-Income Country to Fund Impact Bonds for Early Childhood Development”, Brookings Institution, 6 April 2016. https://www.brookings.edu/2016/04/06/south-africa-is-the-firstmiddle-income-country-to-fund-impact-bonds-for-early-childhooddevelopment

17 AVPN, “About Dasra”. https://avpn.asia/organisation/dasra

18 UBERIS Capital, “Our Portfolio”. http://www.uberiscapital.com/ ventures-portfolio

19 Christa Hangl, “A Literature Review about the Landscape of Social Finance”, ACRN Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives 3, 4 (December 2014): 64–98. http://www.acrn-journals.eu/resources/ jofrp201404b.pdf

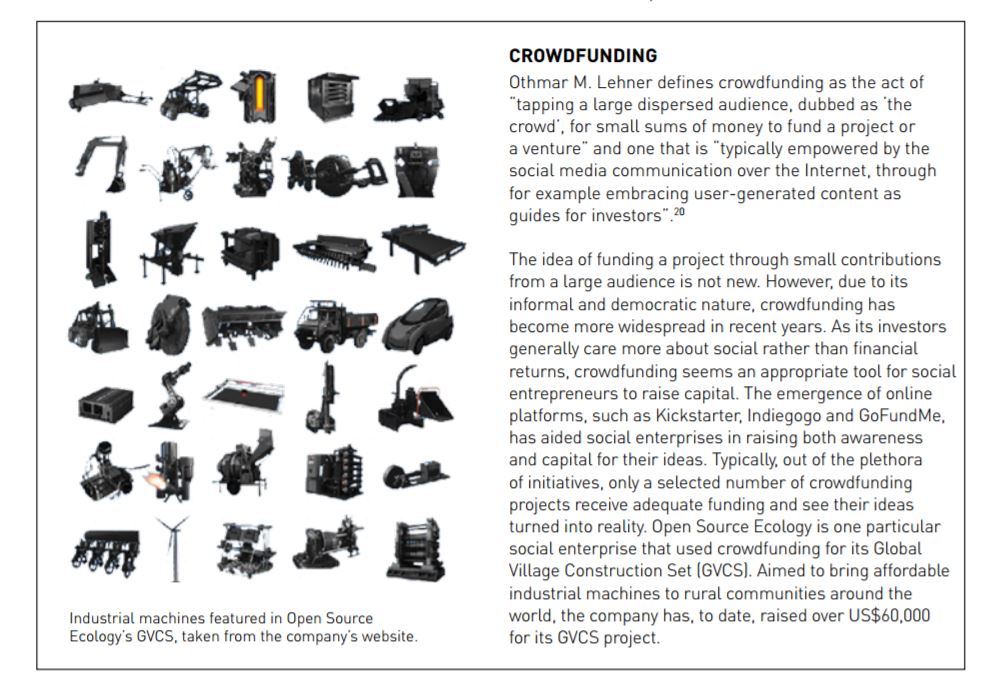

20 Othmar M. Lehner, “Crowdfunding Social Ventures: A Model and Research Agenda”, Venture Capital 15, 4 (2013): 289–311 21 Ellie Howard, Challenges and Opportunities in Social Finance in the UK (London: Cicero Group, 2012). http://www.cicero-group.com/ Research-Analysis/Pain_in_spain_report.pdf 22 Ibid.

Originally from Seoul, South Korea, Haneol Jeong is a student at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and a member of the Joseph Wharton scholars program. He was a Summer Research Associate at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation, where he conducted an independent research project on increasing energy access in Southeast Asia through investment in social enterprises. He can be reached at haneolj@ wharton.upenn.edu

Mitchell Laferriere was a Summer Research Associate at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation. During this time, he studied theory, strategy and developmental curriculum for the teaching of impact investing to university students. His primary research interests cover impact investing, sustainable finance, social entrepreneurship and social innovation. He is currently based in Manhattan, New York, where he attends the Gabelli Business School at Fordham University. He can be reached at mlaferriere1@fordham.edu

John Kinsella is a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania. Originally from Houston, Texas, he earned an Eagle Scout award and received the Princeton Prize Certificate in Racial Relations. He was a Summer Research Associate at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation, during which time he conducted independent research on interdisciplinary solutions to issues facing the world. He can be reached at jkin@sas.upenn.edu

Remi Cordelle is a rising sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania, where he majors in Economics and Computer Science. Formerly a Summer Research Associate at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation, Remi conducted research on income inequality. His areas of interest include social mobility in emerging economies; financial inclusion in Southeast Asia; financial literacy in marginalised communities; social enterprises in Indonesia; microfinance in developed and emerging economies; and leadership in social finance. He can be reached at remicor@sas.upenn.edu

Maaya Murakami, formerly a Summer Research Associate at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation, is a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, where she majors in International Relations and Economics. Born in Japan but raised in the Netherlands and Germany, Maaya’s research interests include ASEAN’s strengthening of social protection measures in its member states, and its challenges and implications; social entrepreneurship in Cambodia; and Germany’s dominance in the management of the European economic crisis. She can be reached at maayam@sas.upenn.edu

Christian Petroskewas an Assistant Manager at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation, where he drove forward a diverse range of projects, including the Centre’s research, capacity-building, partnerships and events. Before joining the Centre, Christian helped Year Up build databased feedback loops into its core decision-making as Sales Operations and Market Research Fellow while participating in a selective, applied management training programme through New Sector Alliance’s Residency in Social Enterprise. Christian holds a BA in Sociology with Honours from Brown University, where he chaired the state’s biggest social enterprise conference, worked with two start-ups and founded one, conducted both applied and academic research, and wrote an award-winning Honours thesis on feedback and power in social finance. He can be reached at hi@christianpetroske.com

Florian Parzhuber is a senior at the Singapore Management University (SMU) where he majors both in Finance and Operations Management. His research interests include water and sanitation systems across different continents, financial inclusion, as well as the future outlook of crowdfunding. He can be reached at fparzhuber.2013@smu.edu.sg

Comments