By Isabella Nuñez

Earlier this summer, I found myself thinking about “allyship” and considering what it can mean. A popular term used in the discourse of social issues, there are in fact many different ways to define allyship, and even more ways to act upon it.

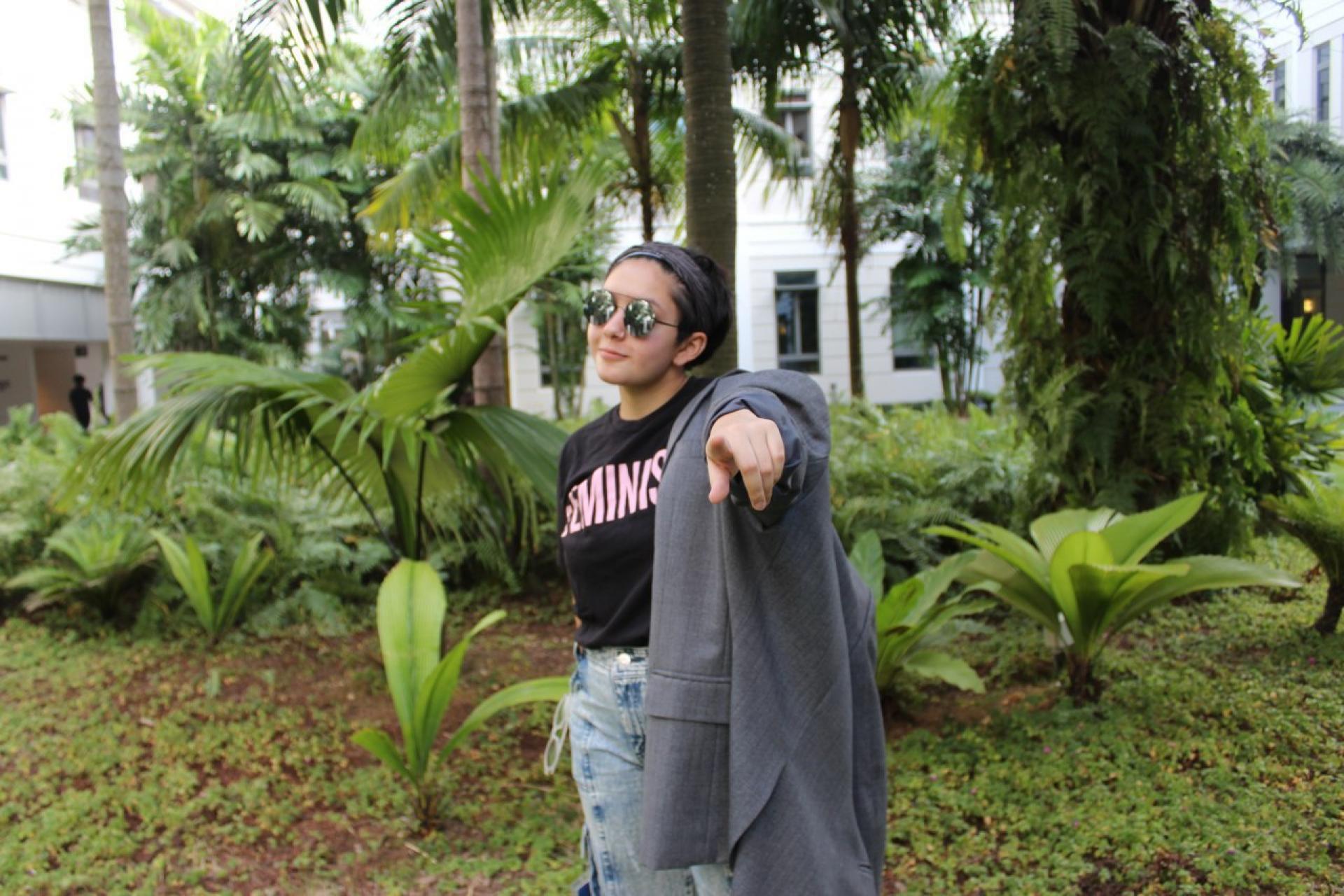

Isabella ("Izzy") on campus, 2019.

My name is Isabella, I come from the United States and I'm an international student at Yale-NUS College. If not for the COVID-19 circuit breaker, I might have returned to the US this summer and be actively supporting the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. This made me think about all the things I’d be doing as an ally for BLM—showing up in the street, supporting Black businesses and people in my life, and talking to my friends and family about the relevant issues. But because I’d remained in Singapore, I could only watch from a distance as the movement rose in popularity in the US and globally. It was then that I realised it was neither legal nor practical for me to try to be an ally for racial justice in the ways I had always understood.

The next question I came to ask myself was this: “How can we be allies for struggles that are far removed from ourselves, physically or socially?” As a Latinx who grew up as a racial minority within the US, it was easy to grasp the importance of being an ally for other racial groups in my country. However, now a student in a foreign country, I'm looking at allyship through a very different lens.

Image via Unsplash.

Allyship can feel like an overwhelming topic to approach because at any one time, there will be many pressing issues needing our attention. In the month of June alone, BLM activists were calling for allies for the Black community; organisers of Pink Dot were seeking support for Singapore's queer community; and various groups were also rallying Singaporeans to fight for migrant worker rights. Globally, there were other calls to uplift marginalised groups that bear the brunt of the COVID-19 impact.

The following sections outline a step-guide of ways to start thinking about and actualising allyship. As you read on, remember this: educating yourself about issues is important, but also take time to educate yourself about your own position in society. A very common mistake for allies is assuming that by knowing an issue exists and by feeling bad about it, they have achieved allyship. This can lead to what has been termed performative allyship. Remember: allyship isn’t an identity, but something you practise.

Izzy weaving the "community loom" at an event with a food justice non-profit in her hometown, 2017.

The Allyship Step-Guide: An Overview

- Allyship starts with self-reflection.

- Allyship needs research.

- Allyship needs action.

- Allyship needs humility and improvement when we make mistakes.

- Allyship needs to be ongoing.

Self-reflection

Why do we need to look at ourselves when allyship is all about thinking about others?

The answer is simple: we won’t know how best to act upon our thoughts unless we first take stock of both our privilege and positionality. This is where self-reflection comes in.

Privilege indicates aspects of our identities we do not have control over (typically, things we were born with) which give us advantages in society. For example, English is my first language and I have a Western accent, so whether in the US or Singapore, I’m able to learn, write and be assessed in my native language. When I started school here, I found it very easy to speak up and participate in classes, until some friends made a remark about “loud American students”. This made me realise that my confidence in class had less to do with my competency, and more to do with my privilege of being native English speaker from the West in a liberal arts setting.

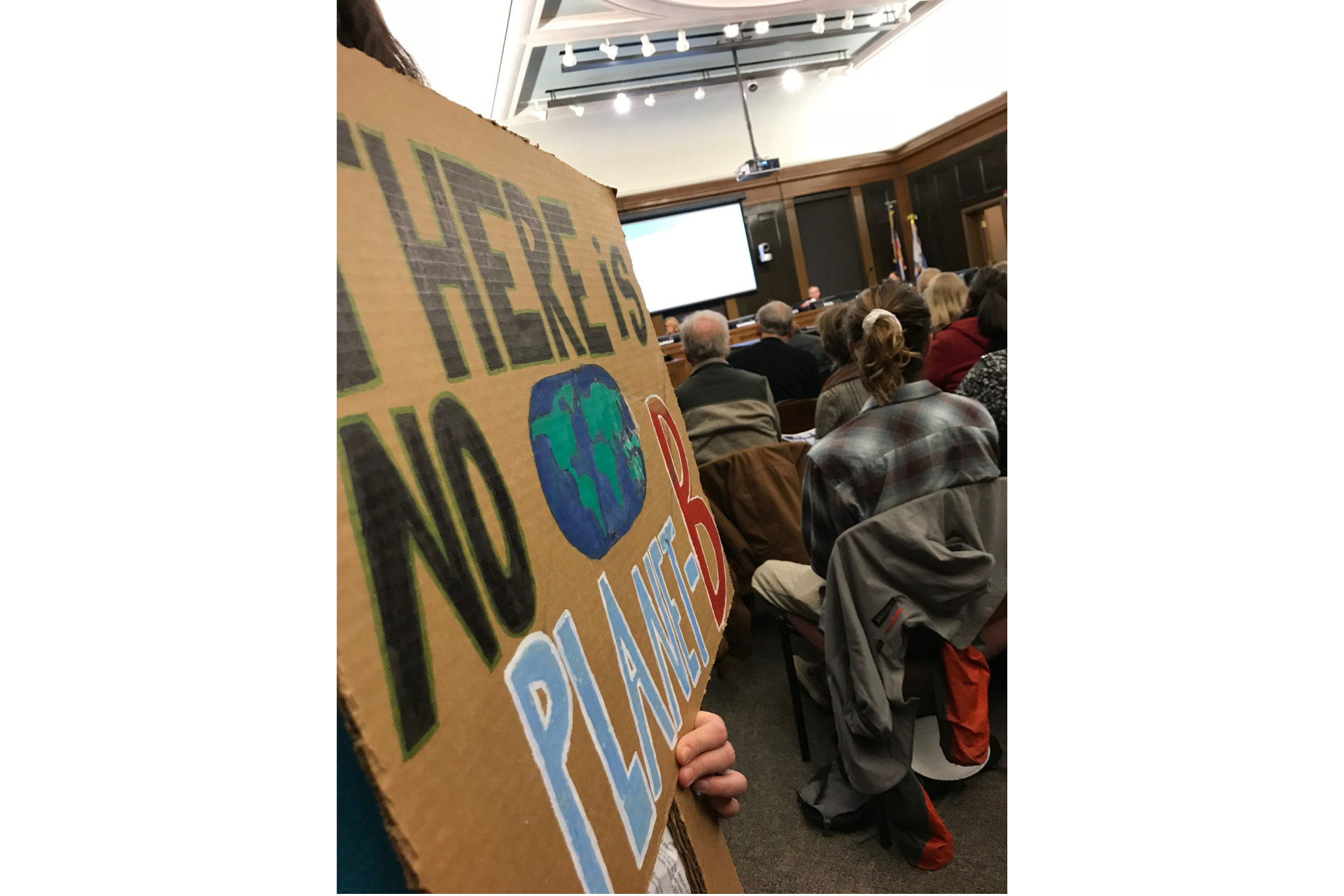

A 2017 town hall in Izzy's hometown of Colorado Springs.

This brings us to positionality. Positionality means considering the identities and privileges we hold in the context of where we are and what we do. For instance, back home in the US, I often take my nationality for granted, but in Southeast Asia, I am conscious of my country's past conflict in the region.

Another thing to consider during self-reflection is that privilege can exist at the same time as marginalisation. For example, members of the LGBT+ community are marginalised by certain structures and policies within Singapore, and yet plenty of LGBT+ people may also be wealthy or of a privileged racial identity. On the topic of allyship, the Inter-University LGBT+ Network writes:

“Our struggles go beyond #repeal377A or not being able to BTO [buy a new government-subsidised flat].…The experiences of LGBTQ+ people vary….The challenges facing a gay man would be, for instance, very different from a transwoman or man.”

In this way, we must also think about allyship means within our communities and across many intersections of identity.

Self-reflection is a process of both learning and unlearning. You learn what your position is in society, as well as unlearn the unconscious biases which that position has given you. The outcome of this self-reflection should be realising that allyship is not about you—it isn’t about fixing your guilt, getting “credit” for being interested in social justice, or playing “oppression olympics” to show one person as more or less marginalised than another. Rather, allyship is about solidarity. This means taking issues on as your own.

As Roxane Gay famously put it:

“We need people to stand up and take on the problems borne of oppression as their own, without remove or distance. We need people to do this even if they cannot fully understand what it's like to be oppressed for their race or ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability, class, religion, or other marker of identity.”

Research

This is typically the easiest step we can take towards becoming allies. In the age of the Internet and social media, we can easily read about other people’s experiences and access resources on becoming an ally. Research is extremely important in allyship because it helps us to avoid spreading misinformation, which can often hurt the marginalised.

In the past, I believed that all religious groups were not welcoming to LGBT+ people. This is a common assumption among the LGBT+ community and their allies alike. With more research, though, I found many queer-affirming religious groups, even ones here in Singapore such as Free Community Church and The Healing Circle. This reinforced my belief in the importance of not operating upon assumptions.

![]()

Image via rawpixel.

We should additionally be mindful that while doing research can be easy for allies, being researched is usually not easy for the people who are experiencing marginalisation. Here are a few key things to note when learning about a social issue that is not affecting you:

- Educate yourself. It is not the job of the oppressed to do that. Before you take action, and before you even hold conversations with the people you want to be an ally to, do plenty of research.

- Practise active listening. When you do hold these conversations, ensure you are making the most of everyone’s time and energy, and make it a respectful experience.

- The conversation may be harder for them than it is for you. Recalling or explaining instances of marginalisation can be emotionally exhausting and sometimes traumatic. As allies, we need to respect when others do not have the energy to talk, or when they have seemingly harsh reactions to our lack of experience. Being conscious of this is exactly why we need to start allyship with our own self-reflection.

Getting Started: Allyship Platforms Worth Checking Out

- Women’s rights: Sayoni (@sayonisg), AWARE (@awaresingapore), Beyond the Hijab (@beyondhijabsg)

- LGBT+ rights: Pink Dot (@pinkdotsg), Young Out Here (@youngouthere), Oogachaga (@oogachaga), The T Project (@thetprojectsg), Inter-University LGBT Network (interunilgbt), Bi+ Collective (@thebipluscollective.sg)

- Migrant worker rights: HOME (@home.migrants.sg), HealthServe (@healthservesg), Transient Workers Count Too (@twc2sg), Welcome in My Backyard (@welcomeinmybackyard)

- Environmentalism: @sgclimaterally, @climateincolour, @theweirdandwild

- Disability: @enablingvillage, @diversability

- Allyship (multiple topics): @cape.sg, @i_weigh

Allyship: A Glossary

- Allyship: When persons of a non-marginalised identity support and act in solidarity with those who have experienced marginalisation, discrimination or violence. “Being an ally” is a concept most commonly used in reference to supporting the LGBT+ community, but it can also be applied to different social issues. Allyship is distinct from advocacy or activism in that it is primarily used in the context of individual actions and education to support causes and people close to us. Advocacy and activism, on the other hand, are about working together with others to challenge systems and effect change.

- Performative Allyship: When people paint themselves as allies simply by sharing trending information or slogans—without the necessary research, action or self-reflection—in order to claim “ally” as an identity for themselves.

- Privilege: An advantage in society (be it social, physical, or economic) which is granted to individuals or communities, most often determined by aspects of identity which they cannot control.

- Positionality: Considering the identities and privileges someone holds in the context of where they are and what they do. Privilege and marginalisation are not absolute, but they are experienced and enacted differently in different social and cultural contexts.

- Unlearning: Interrogating one’s own conscious and unconscious biases, recognising how these may have come about as the result of particular identities, privileges or positions they hold—and taking conscious steps to counter those biases in future actions.

- Active Listening: Listening without judgement, with the intention to fully understand and reflect upon what is being said. Active listening centres the experience of the speaker and is crucial to engaging respectfully as an ally.

- Apologising: A good apology should not only express regret for past actions or inactions; it should also explicitly acknowledge who has been affected and articulate plans for future improvement.

Action

Allyship means asking both “What is the problem?” and “What can I do to help?”

The kind of “action” to take depends on your context and position. Maybe you are financially secure: you can donate to causes you researched. Maybe you hold power at your place of work: you can employ staff with underrepresented identities and make sure your company’s policies make them feel safe. Maybe you are an educator: you can pass values of inclusion, solidarity and allyship on to your students and make sure your educational institution reflects those values. Maybe you hold sway in your home: you can have important conversations about biases and discrimination with family members.

Izzy practising on her guitar in her college dorm.

If you don’t know where to start in terms of action, here are a few acts of allyship which you can apply to almost any social issue:

- Address discrimination within your close friends and family. This can look like speaking up about racism during a family dinner or messaging your aunt to respond to something xenophobic she posted. Although it can be scary and frustrating, having these conversations about topics which may not affect you directly is very important because it takes the burden away from people who are affected.

- Use your platform to spread knowledge and uplift others. Your “platform” can be anything: big or small, online or at work or school. We all interact with people, and that means we all have some place to spread messages of allyship and solidarity.

- Contribute to causes which are working to solve the problem. Besides financially, there are many other ways to contribute through your time, skills or written support. Some good examples are this carrd for BLM, which includes petitions and alternate forms of donating, and in Singapore the Mutual Aid and Community Solidarity spreadsheet created by @wares.

COVID-19 has placed some new constraints on allyship in terms of spaces, movements and finances. However, it has also provided a space to cultivate new avenues for allyship. For example, the new Welcome in My Backyard (WIMBY) campaign, created during the pandemic, has gained considerable traction in Singapore for standing in solidarity with migrant workers. Ethel Pang, a co-lead of the Local Integration wing of WIMBY, shares:

“The first step of allyship is actively listening....It is okay to start from a place of ignorance, or a lack of information, but we have to take the first step to expose ourselves in potentially uncomfortable or new conversations.”

Humility and Improvement

Given the complexities of allyship, it is understandable that we make mistakes along the way.

Maybe you hear a friend crack a homophobic joke, and you don’t step up to question them. Or you catch yourself assuming things about a stranger based on their race. Or you realise you’ve been avoiding conversations about disability because they make you uncomfortable. These are some common ways we may let down individuals or communities by failing to act as an ally. However, there are always opportunities for improvement.

A 2017 demonstration in Izzy's hometown of Colorado Springs, against the DAPL pipeline running through indigenous lands.

First, we need the humility to recognise when we have been part of the problem. Be conscious of your own biases. Be aware of how your action or inaction has affected others. And, when the time comes, be ready to apologise.

Apologies can easily fall short: recent local examples include Marshall Cavendish Education’s statement that the racism in their Chinese-language book, The Amazing Adventures of Pi Pi was a “misunderstanding”, and the claims by OkLet’sGo hosts that criticisms of their on-air misogyny were a “coordinated attack”.

If we hope to move forward from our mistakes as better allies, we need to make a good apology part of our everyday skillset. When you say sorry, address not only what you have done (or not done) and how it affected others, but also what you plan to do to improve in the future.

An Ongoing Journey

Finally, allyship is an ongoing journey, starting from within oneself and gradually impacting our communities. As an ally, we stay the course even if change is not on the immediate horizon. Some issues may not be solved in the near future, but we never quit being an ally the same way we never stop fighting for human rights.

A women's march in Denver, USA, 2017.

As I strive to support the Black Lives Matter movement from Singapore, I’ve been asking myself: “How does BLM apply in my current context?” and “Where am I needed?”—while also examining my existing roles within my immediate community. Maybe I have not or cannot do much for BLM per se, but there are still some things that I can do, such as work to become a better ally for racial justice right here and now. For instance, I can address racism in my school community, my queer community, and among my friends in Singapore.

And this is exactly what readers can take away from this piece—the idea that there is always something within your power to do.

|

Isabella Nuñez was a Marketing & Communications Summer Associate at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation. A third-year student at Yale-NUS College studying Anthropology, her interests include intersectional feminism, meeting dogs, and cycling short distances. She can be reached at inunez@u.yale-nus.edu.sg |

Comments