By Rob John

Over the last six years, I have been researching ways in which philanthropy is developing and innovating across Asia in response to the region’s surge in entrepreneurial wealth creation and the global rise of social entrepreneurship. My working papers and articles at NUS Business School explore topics such as venture philanthropy, impact investing, collective philanthropy and new models of CSR in Asia. I was particularly intrigued by the growth of collective philanthropy—initiatives such as giving circles and “live crowdfunding” events. During these studies, I interviewed individuals who had joined giving circles and who found the experience of giving to non-profits alongside others a positive one. It transpired that several of these philanthropists were also “angel investors” in commercial start-ups and social enterprises. This prompted me to look more closely at how angel investing may be a route for supporting social enterprises in Asia. Let’s begin by looking at what angel investing means.

Community participation in identifying village needs (Photo courtesy of Gram Vaani)

Community participation in identifying village needs (Photo courtesy of Gram Vaani)

Angel Investing

Business angel investment (or simply angel investing) generally refers to a practice in which individuals invest both their money and time into early-stage businesses with the objective of making a financial return and the satisfaction of seeing those ventures thrive. Angels invest alone or in formal or informal syndicates called angel groups or networks. They are typically high-net-worth individuals with business skills and experience. Many are successful entrepreneurs with first-hand knowledge of launching and growing companies, and help to cultivate entrepreneurship around them by drawing on their own acumen.

Angels are important because of the key role they play in funding new business ventures, which when successful are major contributors to economic development through the creation of new jobs and wealth. New venture funding is inherently risky and often shunned by the banking system, especially during periods in the economic cycle when credit is tight. Angel investors fill a funding gap commonly referred to as the valley of death—a period of negative cash flow during the pre-revenue stage of a start-up after funds from family and friends have been exhausted. But funding is not the only critical asset angels bring: their business know-how, and patient understanding of the length of time required before a new business develops into a thriving venture are qualities valued by entrepreneurs.

Using a white cane to find your way in complete darkness (Photos courtesy of Dialogue in the Dark, Hong Kong)

Using a white cane to find your way in complete darkness (Photos courtesy of Dialogue in the Dark, Hong Kong)

The United States dominates the angel investing landscape with about 350 groups scattered across almost every state and hubs in Silicon Valley and Boston. Figures from 2007 suggested that there were over 250,000 angels in the United States who invested US$26 billion in some 50,000 enterprises. The United Kingdom is thought to have up to 6,000 angels who invested up to £1 billion (US$1.6 billion). There are also angel networks in Australia, Canada, China, India, Latin America, the Middle East, New Zealand and Southeast Asia, although data on the size of angel markets in these parts of the world is patchy.

Angel investing helps entrepreneurs bridge funding gaps and grow their early-stage enterprise to a point of maturity when it becomes more attractive to big-ticket investors and lenders. Social entrepreneurs face similar, and often more extreme challenges in fuelling the expansion of their social enterprise. They too must cross the valley of death before being able to unlock growth capital from finance providers such as “impact investors”.

Social Entrepreneurship and Impact Investing

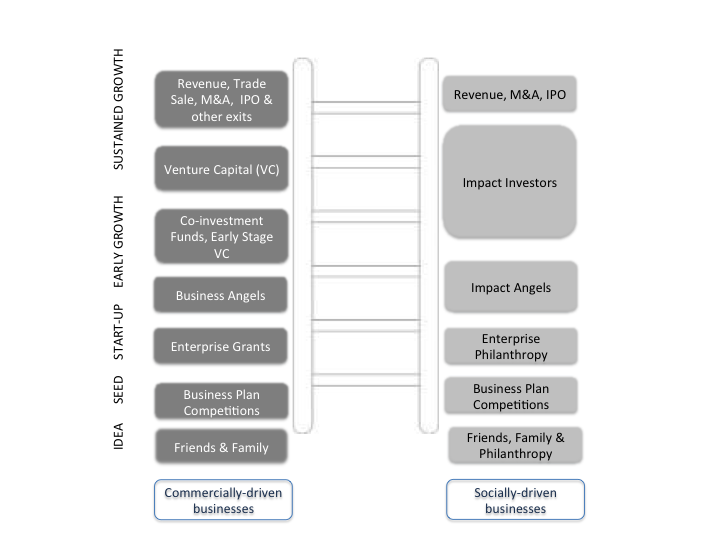

Figure 1 Enterprise Finance Ladder (Adapted from World Bank, Creating Your Own Angel Investor Group: A Guide for Emerging and Frontier Markets, 11).

Without getting into confusing and contested debates about what constitutes social entrepreneurship, it is probably safe to state that social entrepreneurs are individuals who create and build sustainable social enterprises that address social and environmental problems. They use the best of business thinking and practice to create social value. Many social enterprises require continued grant subsidy to fuel growth, while others have business models that generate financial returns for investors. Social entrepreneurs and impact investors are like the intertwined strands of DNA, mutually supporting each other’s mission and growth.

Although the term impact investing was only coined as recently as 2008, its practice is much older. Impact investing has its roots in Program Related Investment, a device pioneered by the Ford Foundation in 1968 that allowed endowed American grantmaking foundations to invest their corpus in support of quasi-commercial entities that fulfilled the foundation’s charitable objectives. Pure philanthropy is always constrained since donations are a one-way flow of capital. The promise of impact investing is to create social value by investing in socially focused enterprises with sustainable business models, which, when successful, preserve capital or offer a financial return. ImpactBase , a global impact investment fund database, lists over 400 impact investment funds with an aggregated US$31 billion assets under management.

Being able to draw from a steady pipeline of good quality, high-potential social enterprises remain the biggest challenge for philanthropists and impact investors. In 2009, Monitor Institute identified weaknesses in the impact investment ecosystem that would hamper its development in the following decade, especially the low volume of social enterprises meeting basic investment criteria. An analysis of historical data from Africa and India led Monitor and Acumen Fund to suggest that philanthropy has a pivotal role to play in creating a pipeline of opportunities for impact investment (a term they coined as “enterprise philanthropy”). Beyond cash from friends, family and philanthropy, early-stage social enterprises have the prospect of growth capital from impact investors. But all too often their enterprises, like their purely commercial cousins, are not yet at a size and profitability to be attractive to impact investors. The “missing rung” in the financing ladder can be provided by angel investors, whose equity and business advice help a social enterprise become investment ready (Figure 1).

Angel Investing for Impact

My primary interest in exploring the role of angel investment for social impact is focused on Asian enterprises and investors, but there are several instructive examples from the United States and United Kingdom (for a selection of these, see Table 1). This is not surprising since angel investing and social enterprise are both well-established practices in these countries.

Table 1 Selected Impact Angel Groups in the US and UK (figures correct in 2014)

| Investors’ Circle (IC) North Carolina and local chapters, USA |

|

| Toniic San Francisco, USA |

|

| Big Venture Challenge (BVC) London, UK |

|

| Clearly Social Angels (CSA) London, UK |

|

During my study on collective philanthropy in Asia, I interviewed individuals who donated to non-profits through giving circles, and made angel investments in commercial and social enterprises. This prompted me to look more widely at impact investing by angels. Although the sample of angels and their networks in my study was modest, it drew me to suggest a simple typology: I observed the migration by traditional business angel groups into impact investing; I found impact angel networks (either independent or embedded within other organisations) and individual angels investing alone or in ad hoc association with others. In the following sections, I illustrate these types of angel investment for impact with selected examples from the study.

Migrating Angels

Business angel networks, which provide their members with a managed platform of investment opportunities in early-stage companies, have only existed in Asia for a decade. The Indian Angel Network (IAN), India’s first formal angel collective, was set up in 2006 by entrepreneurs and has become Asia’s largest, with over 300 angels investing in start-up and early-stage ventures in seven countries.

Many of IAN’s members are both serial entrepreneurs and philanthropists. They realised the potential of using the network’s financial and intellectual resources to help develop scalable businesses that aspire to provide affordable goods and services to those at the base of the pyramid and so create widespread social impact profitably. In 2013, the network launched IAN Impact—a sub-group of angels seeking to invest in social businesses—Asia’s first example of a mainstream business angel network migrating into the social enterprise sector. The impact angels’ first investment was in Gram Vaani, a low-cost, social media platform that empowers rural communities and NGOs. Gram Vaani has more than two million users in India, Afghanistan, Namibia, Pakistan and South Africa. In a step-change for the enterprise, 24 IAN angels co-invested with Digital News Ventures in a funding round valued at half a million dollars. Gram Vaani’s founder, Aaditeshwar Seth, values the angels’ involvement in his business, saying they are “entrepreneurs who know how to grow a company, whose inputs are very useful in helping us overcome bottlenecks in our growth, and who open up their networks to bring us new business.” Angel networks in Mumbai and Kolkata have also migrated towards social enterprise deals to bring their members opportunities to invest in potentially profitable businesses that serve the poorest.

Impact Angel Networks

These angel networks in India migrated from investing exclusively in commercial businesses to support social enterprises with equity and advice. We saw earlier that networks like Investors’ Circle and Big Venture Challenge source exclusively social impact opportunities for their angels. In Asia, we are beginning to see first wave of angel networks dedicated wholly or predominantly to early-stage social enterprises.

In comparison to its neighbour India, Pakistan has a poorly developed ecosystem for supporting entrepreneurs and financing their ventures to scale. Invest2Innovate (I2I) was launched in 2011 to provide a community of angel investors with a pipeline of early-stage social businesses. Successful entrepreneurs must offer a compelling business case that demonstrates potential financial viability. In addition, they need to be an impact enterprise, which I2I defines as “a for-profit business that provides an innovative product or service to address a long-standing social or environmental issue.” I2I’s founder Kalsoom Lakhani describes the need to work at “both ends of the ‘dumbbell’ by strengthening the business skills of social entrepreneurs and educating angels about social impact.” At the front end of its pipeline development, I2I runs a four-month accelerator programme where selected entrepreneurs receive online support and attend residential weekends in either Karachi or Lahore. Training is led by experienced businesspeople on topics such as branding, customer acquisition, financial management and operations. One of the reasons angel networks have not thrived in Pakistan previously is “lack of trust,” says Lakhani. This is the reason why a core value of I2I is to build an investment community “not only to increase access to seed capital for entrepreneurs, but also promote trust and transparency between entrepreneurs and investors, and among investors.”

Other angel groups dedicated to impact investing are embedded in larger organisations, in the same way that Big Venture Challenge and Clearly Social Angels are hosted by their parent organisations. My study identified several embedded impact angel groups in India, hosted by impact investment funds. Intellecap is a group of financial and consulting intermediaries promoting investments in social enterprises that serve the base of the pyramid in India. After 11 years processing multimillion dollar deals in this space, Intellecap noted a growing gap in financing early stage ventures valued at US$1 million or less—the kind of small and medium businesses that also value mentoring and basic business advice. Intellecap launched the Intellecap Impact Investment Network (I3N) as a group of angels providing early-stage capital for ventures in healthcare, education, agriculture, clean energy, financial inclusion and water. By 2014, I3N comprised over 50 angels exploring deal sizes typically up to US$170,000, and able to make individual contributions of up to US$30,000 in addition to offering business advice. I3N enhances its pipeline of investment-ready social businesses for Intellecap’s main investors by connecting angels with small but high-potential enterprises.

Individual Angels and Hyper Angels

In the examples above, impact angels make their investments as members of networks or groups. Angels can also act independently of such platforms, either as lone individuals or in ad hoc collaborations with other angels. Being part of an angel network brings advantages, especially the opportunity to evaluate a deal flow of pre-screened potential investments brought to the network by its executive staff. But angels are also discovering start-up businesses through their own contacts and business networks and choose to invest alone.

In the report of my study, I profiled two successful businesspeople who used their skills and business acumen to support early stage social enterprises and non-profits. One of these is Patrick Cheung, a Hong Kong-based packaging entrepreneur who retired and sold his businesses in 2006 to become one of the island’s committed supporters of social enterprise, most notably as lead angel investor in one of Asia’s most successful social businesses.

The individual angels I interviewed exemplify what Schervish calls “hyperagency” in philanthropy and social investment—the institution- and industry-building capacity of wealth creators who apply their resources, attributes and worldview to the social sector. Such hyper angels as those I profiled are not content to simply invest in isolated social enterprises, but want to contribute to the building of a healthy investment ecosystem. They view the emerging marketplace for social enterprise with the same insights that made them industry and system builders in their business careers. Cheung helped found the Hong Kong Social Enterprise Forum (HKSEF), to foster the social enterprise sector in Hong Kong and mainland China. During a Forum event, Cheung met the CEO of Dialogue in the Dark (DiD), an innovative global franchise of exhibitions that provide able sighted people the experience of the visually impaired. Cheung saw a role for DiD in Hong Kong’s expanding disability movement, and, with the insightfulness of an entrepreneur, believed the organisation could be a profitable social enterprise, and not reliant on the grant subsidy it needed in other countries.

Cheung negotiated a licence to establish DiD in Hong Kong as a social franchise paying a fixed royalty to the parent organisation. He and one other angel put up the initial share capital and over time other angels joined. DiD Hong Kong has been a commercial success while maintaining its core social impact objectives. The enterprise broke even after two years and had sales revenues of HK$20 million (US$2.6 million) in 2014. Trip Advisor rated DiD Hong Kong as one of the top 10 attractions for visitors in 2011—an astonishing feat for a young social enterprise in a major tourist city. DiD Hong Kong returned five per cent of the amount invested as dividends to investors in its first two years and 10 per cent in the third year. A minimum of 35 per cent of any annual net profit is donated to the DiD Hong Kong Foundation for the development of services for the visually impaired.

Entertaining Angels Unawares

Although the focus of my interest was Asia, my observations (together with the examples from the US and UK) suggest a universal role for angel investing in social enterprises. Businesses, whether explicitly social or not, require access to a continuum of funding and sound advice from conception to start-up and early-stage growth. Angels are prepared to take the risks associated with such unproven ventures and help fill the funding and advisory gap between friends, family and philanthropy, and institutional investors.

This article is intended to encourage entrepreneurs and investors. Too many entrepreneurs grow a business idea beyond start-up, and then peer down into the valley of death, unable to bridge the gap to institutional funding. I encourage them to see what angel investment would offer; not only finance but the business skills, insights and networks that seasoned angels can provide. But they should be selective, and enter an angel relationship with eyes wide open. Patrick Cheung counsels social entrepreneurs “to pick their investors very carefully,” avoiding those he describes as “having heard the term social impact but whose motives are financial.”

I also encourage angels who have invested in commercial ventures, but who want to use their resources to create social impact. Social enterprises need their finance and skills. Finally, for successful entrepreneurs and those coming from a corporate career who are not yet angels, consider the opportunities that exist for to use your business experience and resources to help entrepreneurs grow their ideas to successful and sustainable businesses, especially those seeking to maximise public benefit.

|

Rob John is an independent consultant based in Cambridge, England. He spent the last six years researching philanthropy in Asia as a visiting fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Business School, where he examined innovation in philanthropy, giving circles, angel investing for impact and new models of corporate giving. Previously, Rob helped build two philanthropy networks from scratch, EVPA in Europe and AVPN in Asia, as well as studied and wrote about venture philanthropy when he was a visiting fellow at the Skoll Centre in Oxford. Rob’s experience also includes 15 years in international development and microcredit, mostly in refugee communities; and as an academic research chemist at the universities of Oxford, Purdue, Lausanne and Addis Ababa. Visit the Giving Circles in Asia website at http://www.givingcircles.asia; or email him at rob.john@oba.co.uk |

Comments