By Hoe Su Fern

“The quality of urban life is clearly not measured by the scale of monuments, its shopping malls, its commercial extravaganza or its top-down officially regulated activities and festive celebrations, but by the liveable, vibrant and sustainable quality of the environment and the intensity of interactions by participating citizens.” —William Lim, Incomplete Urbanism: A Critical Urban Strategy for Emerging Economies1

Introduction

Cities never stand still. Singapore is no exception. This is palpably evident in the recent disappearance of cherished spaces such as Rochor Centre, Sungei Road Flea Market and Pearl Bank Apartments. As Janadas Devan once aptly stated, “forgetting is the condition of Singapore.” 2 This leads one to wonder: in a cityscape where the only constant is change, how can we foster a sense of place and belonging? How and where do we develop social relations beyond our own homes? Are we still able to form meaningful experiences with others as well as our surroundings?

Photo by Annie Spratt via Unsplash.

Photo by Annie Spratt via Unsplash.

Perhaps we could turn to creative placemaking—which champions arts, culture and creativity as critical elements to improving the quality and vitality of a place—as a viable solution. In particular, our artists and arts spaces could be viewed as creative placemakers who (re)activate our public spaces and transform them into beloved places with infinite capacity to connect communities and grow ideas.

Background: The Emergence of Place Management In Singapore

“More than just physical spaces, great places lift our spirits and connect us with one another. They reflect the essence of the people who inhabit them, and are more meaningful when created and shaped by the communities who use the space.”—URA Draft Master Plan 20193

This need to cultivate a sense of place and belonging has been increasingly recognised by the Singapore government. Since the mid-2000s, there has been a heightened push towards cultivating a more people-friendly and soulful cityscape. During his second National Day Rally speech in 2005, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong shared his vision to rejuvenate Singapore into a vibrant city-home, which he defined as a “city which is full of life and energy and excitement, a place where people want to live, work and play, where they are stimulated to be active, to be creative and to enjoy life.” 4 Lee emphasised the importance of “software” like heritage buildings, a vibrant street life and arts activities in cultivating “heartware”, which would generate a sense of belonging, identity and social cohesion among Singaporeans. The role of the arts in transforming Singapore into a more charming place to work, live and invest in, was formalised in the 2008 Master Plan. 5 To do so, place management was proposed as a key strategy to inject cultural vibrancy and soul into the city.

Mural against an HDB block; photo by Annie Spratt via Unsplash.

The Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) refers to place management as “a coordinated, multi-stakeholder approach to improving precincts and making them more attractive for the benefit of its users.” 6 In 2009, the Place Management Coordinating Forum (PMCF) was established to coordinate place management efforts. This inter-agency group is spearheaded by the URA but includes government agencies such as the National Arts Council (NAC), National Heritage Board (NHB), National Parks Board (NParks) and Singapore Tourism Board (STB). That same year, a National Place Management Framework was jointly developed and officially endorsed as a whole-of-government strategy. Since then, place management has been actively endorsed and enforced as a viable urban rejuvenation strategy that has tremendous social, economic and cultural benefits. Notably, this whole-of-government promotion of place management has greatly influenced arts and cultural policy and planning. The latest cultural policy—the Arts and Culture Strategic Review—recommends place management as an effective strategy to shape and enliven the distinct cultural identities of spaces, by broadening access and increasing participation in arts and culture. 7 This was recently elaborated by Rosa Daniel, Deputy Secretary of the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth and Chief Executive Officer of NAC. Daniel identifies place management as the integration of urban planning, cultural policy and community engagement, to collectively create “contexts for positive interactions and shared experiences, emotionally anchoring Singaporeans to places, spaces and community.” 8

Not Uniquely Singapore: Contextualising Place Management as Part of a Global Movement

“There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.” —Jane Jacobs, “Downtown is for People”9

Place management is not entirely unique to Singapore. As Jason Chen, Director of Place Management at URA, acknowledges, it is similar to another globally popular strategy known as creative placemaking. 10 He also recognised that the two terms have been used interchangeably in Singapore, as they share similar objectives of improving and shaping a place. However, while place management and creative placemaking may share analogous aims, where they differ is that place management is top-down, deliberately planned and result-oriented. The concept of creative placemaking first originated in the 1960s, when urban activists like Jane Jacobs and William H. Whyte advocated for a community-driven approach to designing cities for people, rather than for cars and shopping malls. However, the concept only gained global traction from 2010. This was precipitated by the positive results obtained from the release of the Creative Placemaking White Paper by the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) in the United States. 11 The White Paper characterises creative placemaking as a process whereby “partners from public, private, non-profit and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighbourhood, town, city or region around arts and cultural activities.” 12 Importantly, this White Paper provided a policy frame which has allowed the NEA to secure a historically unprecedented amount of funding, investors and resources for the instrumentalisation of art-led practices for civic, social, economic and environmental goals. From its inception in 2011 to early 2017, the NEA, through its nation-wide consortium ArtPlace, managed to secure funding of US$87 million for 279 creative placemaking projects in 208 communities of all sizes across the United States.

Image via rawpixel.com

Image via rawpixel.com

Inspired by the NEA’s success, governments across the world—especially those in global cities like London, New York and Melbourne—have identified placemaking as a key urban rejuvenation strategy. For instance, in July 2017, the City of London Corporation, together with four leading arts, culture and learning institutions (the Barbican, London Symphony Orchestra, the Museum of London and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama), launched Culture Mile. 13 This partnership aims to activate and transform the North West corner of the Square Mile of the city—stretching from Farrington to Moorgate—into a cultural hub for creative enterprise and exchange. It aspires to achieve this by encouraging better links between the venues in the area, as well as through consistent programming of pop-up performances, art installations and inclusive events to animate the public spaces in between the venues and attract diverse audiences to the area. Creative placemaking has also been adopted by communities, artists and arts organisations as a means to engage communities. Founded and led by artist Theaster Gates, the Rebuild Foundation is an arts-centric platform for the revitalisation of underserved black neighbourhoods in Chicago. 14 A meaningful project is the Stony Island Arts Bank in south side Chicago, which was once a disused and derelict bank building that Gates bought from the City of Chicago for US$1 in 2012. Today, the building is a thriving multidisciplinary arts centre that serves as a repository for African-American culture and history, an arts laboratory for the next generation of black artists, and a space for neighbourhood residents to access, preserve, share and reimagine their heritage.

Theaster Gates; photo by World Economic Forum via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Art Block, 15 a free creative space by South London Gallery, is another commendable case study of creative placemaking as a community-driven and arts-centric process. Located in a public housing council estate in London, it is a venue for local children and families to play and be creative. In Malaysia, Think City’s community-driven projects have activated and held numerous spaces, resources and programmes for the nation’s arts and heritage sectors. 16 These include Art Printing Works, 17 an adaptive reuse project that transformed an underutilised commercial printing factory in Kuala Lumpur into a lively creative cluster. It must be noted that while place management may be a relatively new policy in Singapore, practices of creative placemaking are not novel. Performing arts groups such as Drama Box 18 and Spell#7 19 have long been creating projects that engage communities and/or their surroundings. For instance, since 2007, Drama Box has been devising a site-specific series called IgnorLAND, which brings audiences to places to uncover and connect with the stories of the communities that belong to the place. For the 2014 edition, the production team engaged and worked with the residents of Bukit Ho Swee over a prolonged period to obtain their buy-in and share their stories. Consequently, not only did the production feature the heartfelt narratives of the residents, the residents themselves became the performers. There is also Both Sides, Now , 20 Drama Box’s multi-year project examining end-of-life issues. Together with ArtsWok Collaborative and other partners, the current phase of Both Sides, Now involves working with, and engaging in sustained conversations with communities in Chong Pang and Telok Blangah.

Both Sides, Now; photo courtesy of Zinkie Aw.

Both Sides, Now; photo courtesy of Zinkie Aw.

Unfortunately, as creative placemaking is increasingly bandied about by planners and developers as a kind of be-all-and-end-all panacea to any urban ill, it has meant that the term and its expected outcomes of vibrancy, buzz and liveability have become nebulous, expansive and fluid. This elusiveness of creative placemaking has resulted in the challenge of evaluating and assessing outcomes, since creative placemaking projects tend to vary considerably in terms of disciplines, methodologies, values, goals and context. Hence, although place management may be a government-driven process, the Singapore government should be commended for mutating and morphing the global concept of creative placemaking into a context-specific tailored approach that takes into account domestic conditions, particularly the dominance of state ownership of land in Singapore.

Place Managing through Art Festivals: Is It All Just for the ‘Gram?

Place management in Singapore is mainly achieved through the demarcation of precincts in Singapore, which are usually administered and activated by place managers from government agencies in the PMCF. For example, the NHB is the place manager for the Bras Basah.Bugis (BBB) precinct because of the cluster of museums and heritage sites in the area. Meanwhile, the STB place manages Orchard Road, Chinatown and Little India. Currently, the majority of place management precincts are located in the central areas of Singapore, although more precincts outside the central area, such as Jurong Gateway and Paya Lebar, were identified in late 2018. 21 Significant government funding has been invested in the precincts located within the city centre. Notably, in 2015, the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY) announced a $740 million plan to revitalise the Civic District into a “integrated arts, culture and lifestyle precinct”. 22 Soon after, the National Gallery Singapore (NGS), housed in two national monuments (City Hall and the former Supreme Court), opened its doors as the largest visual arts venue and museum in Singapore.

National Gallery Singapore; photo by Jocelyn Wu via Unsplash.

National Gallery Singapore; photo by Jocelyn Wu via Unsplash.

More recently, URA’s Draft Master Plan 2019 23 recast a spotlight on the central area of Singapore. It proposes to “make Singapore’s CBD Great Again” by further enabling a wider diversity of uses in the public realm, including arts programming and activities. Art festivals are a common strategy used to activate city precincts like the Civic District. 24 In particular, light art festivals that activate the night economy have been exceptionally popular. For instance, Light to Night in the Civic District and iLight Marina Bay have become a commonplace, standardised fixture. The Night Festival, organised by the NHB and supported by MCCY, was the first of its kind in Singapore. It originated from the desire to enliven the BBB precinct, and to create accessible touchpoints for the museums in the precinct to engage with new audiences. The Night Festival began in 2008, but has since grown to become the nation’s largest outdoor art festival. 25

The National Museum of Singapore during The Night Festival 2014; photo by ProjectManhattan via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The National Museum of Singapore during The Night Festival 2014; photo by ProjectManhattan via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Indeed, one of the key objectives of The Night Festival is to ensure that it is accessible to all Singaporeans. As described by Festival Director Angelita Teo, “the festival is curated with different entry points in mind, to make sure everyone experiences the arts in a positive way.” 26 To date, every edition has presented a diverse and multidisciplinary line-up of local and international programmes that are mostly non-ticketed. In 2018, festival participants could view museum exhibitions at night, try out printmaking at The Substation, or watch live action stunts in the public spaces. Thanks to the lively programming, the more recent editions of The Night Festival have attracted at least half a million festival-goers, many of whom are returning audiences. Importantly, such festivals are not just about impressive displays of night lights—they are also vital visible reminders that the city should be fun, playful and encourage public sociability. The Night Festival also offers a platform for both emerging and established local artists and organisations to showcase new works. The organising team has continuously strived to commission and support local artists and organisations to offer innovative programmes, and promotes them to other festival platforms like White Night in Australia. Although the place managers themselves take the lead in the programming, occupants within precincts are also encouraged to activate and generate vibrancy as precinct stakeholders. 27 The many arts groups located within the BBB precinct have actively contributed to the Night Festival’s diverse programming. One such stakeholder is Centre 42, 28 a non-profit theatre development space at Waterloo Street.

Photo courtesy of Centre 42.

Photo courtesy of Centre 42.

For the past three years, it has offered Late Night Texting (LNT), which is a showcase of text-based works by emerging artists and arts groups. LNT offers a refreshing addition to The Night Festival, which tends to be associated with spectacular and dramatic creative displays such as fire stunts and acrobatics. It allows audiences to encounter a rich assortment of new ideas and works-in-progress by local artistic talents in “bite-sized” 30-minute experiences. For example, in 2018, audiences enjoyed over 30 performances from four dissimilar theatre collectives. These took place across two nights in a variety of spaces within the Centre 42 site.

From Place Management to Placemaking: The Importance of Making Space—and Holding Space

Since it opened in 2014, Centre 42 has been providing a consistently conducive environment for art-making, particularly in terms of providing a safe space for incubation and experimentation for emerging and/or independent artists. This space to try and experiment without pressure is critical for artists to create new, avant-garde, non-market-led works. The provision of a consistently conducive environment has enabled Centre 42 to foster positive bonds and networks with numerous artists and arts groups. In fact, LNT would not have been possible without this. Company Manager Ma Yanling described LNT as a “big risk” for Centre 42 to undertake, as they were then a young organisation whose core focus is in incubating text-based works rather than in presenting or producing. 29 What Ma did was to capitalise on Centre 42’s most invaluable asset—their social capital, 30 which also enabled LNT to stay true to their core focus. As she explicates, “what we had was two to three years of relationships with artists and arts groups who had trust in us, and whom we also had confidence in, particularly their ideas and processes of creation.” Consequently, LNT has become a productive platform for both artistic and audience experimentation, as it allows artists to testbed new ideas and/or works-in-progress to a live public audience at low risk, while lowering the barrier to entry for audiences to explore and cultivate new tastes.

LNT 2017; photo courtesy of Centre 42.

LNT 2017; photo courtesy of Centre 42.

Additionally, LNT demonstrates how state-led place management programmes hold immense potential to activate latent capacities for creativity. The Centre 42 team challenges and expands the scope of artistic activity by programming manifold interpretations of “text-based work” from spoken word poetry to improv comedy. For instance, in 2017, the front courtyard featured spoken-word talents from Destination: INK, who performed a wide spectrum of genres, from poems that combine word and music, to sci-fi poetry. In 2018, the same space was used by multilingual experimental arts collective GroundZ-0 to perform street Wayang acts. Apart from enabling possibilities for new ways to programme and present the arts to varied audiences, LNT has also successfully advanced artistic experimentation. For independent theatre-maker Thong Pei Qin, programming a series of play readings collectively called Seedy Stories in the nooks and crannies of Centre 42’s building for LNT in 2016 enabled her to advance her practice and explore the possibilities of doing roving theatre. In 2018, Thong staged Bitten: A Return to Our Roots, a site-specific performance in Kampong Bugis. 31 One of the play readings—GFE by artist Choon Woon Yong—was selected to be staged as a full length production by W!ld Rice for their Singapore Theatre Festival in 2018. 32 Hence, not only is LNT a prototypical testimony of how place management/making works best when it allows artists to do what they do best, while encouraging them to engage in community collaborations; it also demonstrates how the core of place management/making is founded on social capital.

Installation outside the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore; photo by Annie Spratt via Unsplash.

Much of Centre 42’s social capital is fostered from how the team has enabled the space to become a quotidian haunt for many artists, who drop by for a chat or when they require seemingly mundane resources like WIFI or a temporary workspace. Another community space that has recently emerged is the Practice Tuckshop, 33 just two doors away from Centre 42. Run by long-standing bilingual theatre company The Theatre Practice, 34 Practice Tuckshop aims to be a “collaborative creative playground that brings various communities and artists together in less formalised contexts”. To enable the space to become more socially inclusive, particularly to residents and non-creatives, it has introduced cross-disciplinary programmes, especially ones that feature food, as an accessible premise to trigger conversations and stories. For instance, it runs a bi-monthly programme called Recess Time, a pop-up communal lunch experience featuring surprise chefs and that include friends and family of The Theatre Practice. To ensure environmental sustainability, the team also works with SG Food Rescue, 35 a social organisation that collects and reuses unsellable produce from vegetable and fruit suppliers. Social spaces like Centre 42 and Practice Tuckshop that connect people and nurture stronger relationships are essential. Artistic Director of The Theatre Practice, Kuo Jian Hong, believes the company’s most valuable assets are “its people and the relationships fostered over the years”, and referred to Practice Tuckshop as an expression of that belief. 36 Indeed, physical spaces that can become part of the daily rhythms of our everyday lives are critical to forming affective relations. They encourage the encountering and embracing of difference.

The Theatre Practice, housing Practice Tuckshop, located along Waterloo Street, Singapore; photo via Flickr.

The Theatre Practice, housing Practice Tuckshop, located along Waterloo Street, Singapore; photo via Flickr.

As sociologist Barry Wellman describes, communities comprise “networks of interpersonal ties that provide sociability, support, information, a sense of belonging and social identity.” 37 Therefore, apart from weaving our social fabric, these spaces also seed creative explorations and increase possibilities for partnerships and collaborations. Ava Bromberg, co-founder of experimental cultural centre Mess Hall in Chicago, calls such spaces “possibility spaces”. 38 She describes them as accessible and inclusive spaces, which promote an environment of “generosity, conviviality, and the messiness of coexisting differences, as well as an openness that allows new ideas and forms to take shape in favour of habitual responses or patterns”. Importantly, possibility spaces promote creativity as a public good.

Turning to the Artist as Creative Placemaker who Cultivates Cultural Assets and a Sense of Belonging

Both Centre 42 and The Theatre Practice are spatially embedded as part of a complex cluster of arts housing spaces along Waterloo Street. 39 Although place management only emerged in 2008, there has been a concerted effort to cluster the arts and culture in the BBB since the 1990s. Today, the BBB is a multilayered, multifaceted area that has weathered tremendous transformation. This is seen in the agglomeration of museums, including the National Museum of Singapore and Singapore Art Museum, and the demolition of such cherished spaces as the Old National Library building, the former Cathay Building and the original Raffles Institution campus.

The Singapore Art Museum; photo by ProjectManhattan via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Singapore Art Museum; photo by ProjectManhattan via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Every space has a history, a culture and connections to the other spaces around it. As idea-makers and story-tellers, artists are able to create unique, uplifting stories that inspire curiosity and a sense of discovery; and most crucially, build emotional connection to places. As both the Night Festival and LNT have demonstrated, these stories can take the form of diverse formats, be it immersive theatrical experiences, poetry slams, dance theatre, experimental music nights, or that which is yet to be defined. These will appeal to different demographics and provide them a reason to linger and have deep encounters with the city. Place managers and policymakers should value this ability of artists as storytellers who are able to find what is authentic about a place, build on it and celebrate it. By doing so, artists can leverage our cultural assets to reimagine possibilities, transform the physical, social and economic identity of our spaces, and create emotional connections between people and spaces. Not only will such artistic content add dimension and depth to spaces, it will also enrich our understanding of who we are as a nation and as Singaporeans. We will thus get to explore the diverse stories of our experiences and histories of our physical infrastructure, particularly the unseen, unheard and even unacknowledged, and deepen our sensitivities to our environment. An example is “Four Horse Road” by The Theatre Practice, which was a site-specific immersive performance tour inspired by the “buried stories and forgotten people” of Waterloo Street and its surrounding areas. The production involved historical vignettes situated in ten locations across three heritage buildings, including The Theatre Practice and Centre 42. “Four Horse Road” highlights how artists are able to craft creative dialogue between the past and present, to foster a sense of connection and belonging with our perpetually-changing cityscape.

Conclusion: From Celebrating Vibrancy to Vernacular Creativity and Conviviality

Overall, this article has demonstrated the generative potential of creative placemaking to alter our experience of city life. By enabling a rich plethora of arts-centric opportunities and sites for people to learn, create, share ideas, and collaborate “together-in-difference”, 40 it will spark unexpected possibilities and let us experience deep, unexpected encounters with the city. Creative placemaking thus celebrates the capacity of the arts to address the city as a complex ecosystem of vibrant symbolic creativity that is ever in flux. As architect William Lim pertinently reminds us, we must recognise the city as being in a vital “state of incompleteness”, with spaces that are indeterminate and open to continuous unforeseen changes and unplanned growth. 41

Goodman Arts Centre; photo by Smuconlaw via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Goodman Arts Centre; photo by Smuconlaw via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Today, apart from the BBB precinct and state-initiated festivities, artists and arts organisations in other clusters have also been practising creative placemaking in their own meaningful ways. Since its move to the Goodman Arts Centre, ArtsWok Collaborative 42 has been working with the Cassia Resettlement Team to develop and implement Cassia Kaki, an arts-based community project to engage the relocated seniors of Cassia Crescent. Goodman Arts Centre is also home to music tenants such as The Observatory 43 and SAtheCollective, 44 who regularly open up their studios and hold jamming sessions and informal gigs for musicians and music-lovers to get together. Meanwhile, the Intermission Bar 45 at The Projector has become a social hub as well as venue for a diversity of cultural activities, ranging from music gigs to film quiz nights and drag performances. We must also not forget about the interstitial spaces, independent creatives and informal collectives who hold space and make room for the multiplicity of voices, approaches and non-consensus.

Block 52 Cassia Crescent; photo by Leexueli95 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Block 52 Cassia Crescent; photo by Leexueli95 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

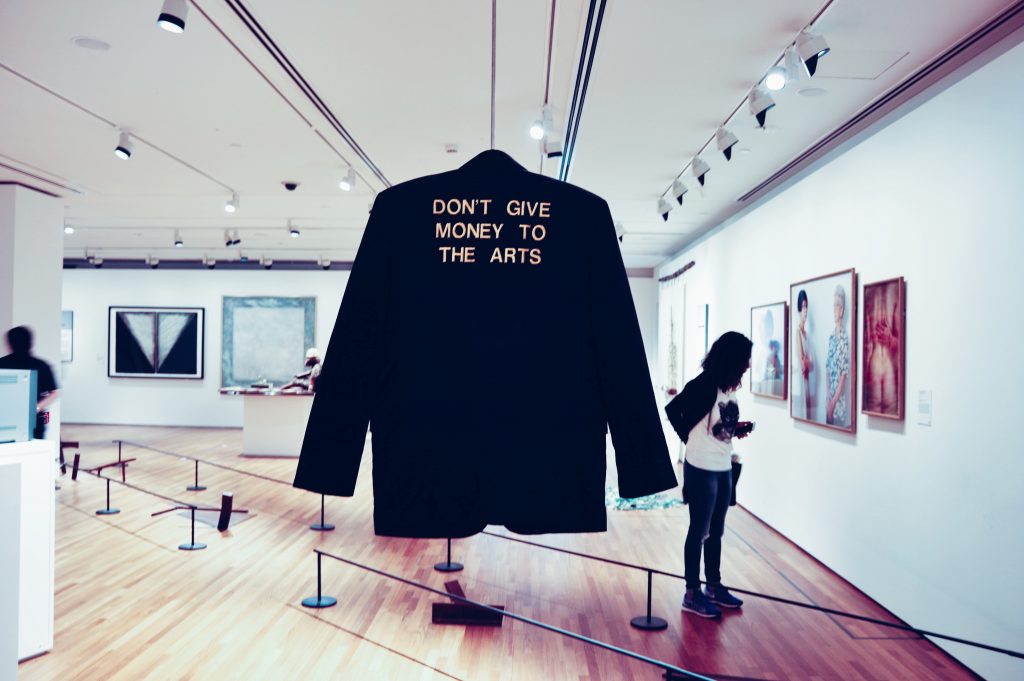

However, like the cityscape, creative placemaking is not a static entity. Rather, it is an ongoing process and in a state of constant reinvention and reinterpretation. The continual dependence on government funding and their focus on tangible key performance indicators is a cogent challenge that limits the latent capacities of the arts in Singapore. This is particularly in terms of sustaining possibility spaces and embracing their tendencies towards messiness and unpredictability. Importantly, there is the urgent question of sustainability, especially in terms of instrumentalising arts programming as a place management strategy. There is a seeming conflation of place management and its expected outcomes of accessibility, vibrancy and buzz with activating spaces through non-ticketed arts programming and high footfall. Mainstream state media reports tend to focus on the quantifiable outcomes of arts programming. This is evident in the recent Straits Times article about the 11.3 million visitors to non-ticketed arts and cultural events in 2017. 46 While increasing accessibility to the arts should be strongly encouraged, the current fixation with trying to grow arts audiences through non-ticketed arts programming has not been adequately supported or matched by robust research or sustained cultural data. As non-ticketed arts programmes are often state-funded, they pose increasing competition to independent and/or smaller organisations that have to charge tickets for survival. As Alan Oei, artist and current Artistic Director of The Substation, cautions, there is a need to cultivate an engaged public instead of attracting mere passive receivers. 47

The Cathay, formerly the Cathay Building; photo by Nlannuzel via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Cathay, formerly the Cathay Building; photo by Nlannuzel via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Therefore, this article calls for place management policies and programmes to move beyond marketable outputs, conspicuous consumption and high footfall. Instead, it should gravitate towards supporting what social scientist Paul Willis describes as a “grounded aesthetics,”48 which means being cognisant of, and actively supporting, the arts in offering quotidian spaces and practices of vernacular creativity. Not only will cherishing our artists and arts groups as creative placemakers result in a more progressive and integrated approach to urban planning and community-building; it also makes possible a rethinking of the synergies between the arts, community and our urban environment. This will empower Singapore to move closer to becoming a more holistic, diverse, resilient and loving society. In 1968, our first Minister of Culture S. Rajaratnam argued for the importance of the artist as a provider of “the emotional and psychological flesh and blood for the bare economic and political structure of our society”. Speaking at the opening of the Singapore Festival that was also a fund-raiser for arts infrastructure, Rajaratnam likened artists to the “microscopes and telescopes which magnify or bring near aspects and secrets of life which were hidden from less perceptive men”. As man should not live by bread alone, he defined a dynamic and thriving society as one in which “there is a harmonious and rational preoccupation with both art and bread-and-butter problems”. 49 Rajaratnam’s remarks are a timely reminder of how we can transform the current policy fad of place management into opportunities that harness the intrinsic value of the arts to Singapore. The arts and artists are to be valued not just as economic fodder or city imaging machines, but as integral to the holistic evolution and betterment of society. Creative placemaking enables exposure and immersion in the arts at the most ordinary spaces and unexpected everyday moments. Through such constant engagement in the arts, Singaporeans—especially the children—will learn to care for others and their environment, as well as open their imaginations, and dream just a little bigger.

Notes

1 William S.W. Lim, Incomplete Urbanism: A Critical Urban Strategy for Emerging Economies (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2012).

2 Janadas Devan, “My Country and My People: Forgetting to Remember”, in Our Place in Time: Exploring Heritage and Memory in Singapore, ed. Kwok Kian Woon, Kwa Chong Guan, Lily Kong and Brenda S.A. Yeoh (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 1999), 21–33.

3 Urban Redevelopment Authority, Draft Master Plan 2019, https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Planning/Draft-Master-Plan-19

4 Lee Hsien Loong, National Day Rally 2005 Speech in English, delivered at University Cultural Centre, Singapore, 21 August 2005.

5 Urban Redevelopment Authority, Master Plan 2008 (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 2008).

6 Hoe Su Fern and Jacqueline Liu, “IPS-SAM Spotlight on Cultural Policy Series Two: Full Report on Roundtable on Place Management and Placemaking in Singapore”, Research Collection School of Social Sciences, Paper 2215 (Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies, 2016); Hoe Su Fern, “Place Management/Making: The Policy and Practice of Arts-Centred Spatial Interventions in Singapore”, in The Urban Imaginative in the Hard State, Soft City of Singapore, ed. Simone Chung and Michael Douglass (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, forthcoming).

7 Ministry of Information, Communication and the Arts, The Report of the Arts and Culture Strategic Review (Singapore: National Arts Council, 2012).

8 Rosa Daniel, “Reimagining Singapore: Placemaking through Arts and Culture”, Ethos 19 (2018).

9 Jane Jacobs, “Downtown Is for People”. Reproduced in The Urban and Regional Planning Reader, ed. Eugénie Birch (London and New York: Routledge, 2009 [orig. publ 1958]), 126–31.

10 Hoe and Liu, “Full Report on Roundtable on Place Management and Placemaking in Singapore”, 2016.

11 Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa, Creative Placemaking White Paper (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 2010).

12 Ibid.

13 Culture Mile website: https://www.culturemile.london

14 Rebuild Foundation website: https://rebuild-foundation.org

15 Art Block website: https://www.southlondongallery.org/projects/art-block

16 Think City website: https://thinkcity.com.my

17 More about Art Printing Works: https://thinkcity.com.my/project/adaptive-reuse-apw

18 Drama Box website: http://dramabox.org/eng/index.html

19 Spell#7 website: http://www.spell7performance.org

20 Both Sides, Now website: http://www.bothsidesnow.sg

21 Grace Leong, “Nine Precincts Join Scheme to Inject Buzz into Public Spaces”, The Straits Times, 18 September 2018.

22 Akshita Nanda, “Singapore Budget 2015: $740 million Invested on Civic District Revamp”, The Straits Times, 12 March 2015.

23 URA, Draft Master Plan 2019.

24 Tong Ming Chien, “Arts District to Foster Creative Spirit”, The Straits Times, 3 March 1995.

25 Casandra Wong, “A Decade on, S’pore Night Festival Sees 800 per cent Growth in Visitors”, TODAY, 19 August 2017.

26 Cam Khalid, “52 Weeks of #excitingSG: Week 26 with Angelita Teo”, TimeOut Singapore, 10 August 2018; Geoffrey Eu, “Weekend Interview: Angelita Teo”, Business Times, 21 October 2017.

27 One notable method used by URA is the Business Improvement District (BID) model. A BID is a business-led and -funded body formed by stakeholders in the area, which votes to invest as a group in improving their local area. An example of a BID is the Singapore River One (SRO) association, which is a private-sector driven initiative established in 2012 by the major business operators active in Boat Quay, Clarke Quay and Robertson Quay. There are currently ten BIDs across Singapore, including Kampong Glam, Paya Lebar and Tanjong Pagar.

28 Centre 42 website: http://centre42.sg

29 Personal correspondence with author, May 2019.

30 Robert Putnam defines “social capital” as the “social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness” that arise from the connections among individuals. Robert Putnam, “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital”, Journal of Democracy 6, 1 (1995): 65–78.

31Bitten: A Return to Our Roots is a site-specific performance staged at Kampong Bugis in 2018 by Thong Pei Qin and Nidya Shanthini Manokara, both of whom were inspired when they fell prey to the Aedes mosquito. The production was based on historical research and communal stories about Kampong Bugis. It was first supported by Centre 42’s Guest Room programme in 2016, and later supported under the Basement Workshop in 2018.

32 More about the Singapore Theatre Festival: https://www.wildrice.com.sg/component/tags/tag/singapore-theatre-festival

33 Practice Tuckshop website: https://www.practice.org.sg/en/tuckshop

34 The Theatre Practice website: https://www.practice.org.sg/en

35 SG Food Rescue website: https://sgfoodrescue.wordpress.com

36 The Theatre Practice, Practice Tuckshop Annual Report 2017 (Singapore: The Theatre Practice, 2017).

37 Barry Wellman, “Physical Place and Cyberplace: The Rise of Personalised Networking”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 25, 2 (2001): 227–52.

38 Ava Bromberg, “Creativity Unbound: Cultivating the Generative Power of Non-Economic Neighbourhood Spaces”, in Spaces of Vernacular Creativity: Rethinking the Cultural Economy, ed. Tim Edensor, Deborah Leslie, Steve Millington and Norma Rantisi (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), 214–25.

39 Arts housing spaces are subsidised work spaces managed by the National Arts Council for arts groups and artists.

40 Ien Ang, I. On Not Speaking Chinese: Living Between Asia and the West (London and New York: Routledge, 2001).

41 Lim, Incomplete Urbanism.

42 ArtsWok Collaborative website: https://artswok.org

43 The Observatory website: http://www.theobservatory.com.sg

44 SAtheCollective website: http://sathecollective.org

45 Intermission Bar website: https://theprojector.sg/cafe

46 Akshita Nanda, “Record 11 million Watched Free Arts and Cultural Events in 2017”, The Straits Times, 25 January 2019.

47 Alan Oei, “As Cities Become Brands and Deploy Art to Create Identity, Can Culture Exist as a Contested Space?”, Art Review Asia (November 2016); Amanda Chai, “The Impossible Feat of Being an Artistic Director in Singapore”, Sg Magazine, 18 April 2019.

48 Paul Willis, “Symbolic Creativity”, reproduced in Studies in Culture: An Introductory Reader, ed. Ann Gray and Jim McGuigan (London: Arnold, 1993), 208–16.

49 Chan Heng Chee, The Prophetic & the Political: Selected Speeches & Writings of S. Rajaratnam, ed. Obaid Ul Haq (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1987).

|

Hoe Su Fern is an arts researcher, educator, coordinator and advocate. She graduated with a PhD in Culture and Communication from The University of Melbourne, and is currently Assistant Professor and Programme Leader of Arts and Cultural Management at the Singapore Management University. Her research interests include arts and cultural policy studies, urban cultural economies, arts spaces and placemaking. Su Fern’s research is informed by her pursuit for practice-oriented and engaged arts research, and her desire to enhance research impact beyond academia, particularly through the power of the arts to catalyse dialogue and bridge differences. She can be reached at sfhoe@smu.edu.sg |

Comments