By Trang Chu Minh

Despite the rise of socially responsible businesses and conscious shoppers, the fashion industry seems to be falling behind. It is common to read reports of clothing brands whose ethics and manufacturing practices are called into question—some even accused of slavery in their supply chains. But errant retailers aside, one still wonders: given the seasonal nature of what’s “on trend” and the prevalence of “fast fashion”, can this industry ever break out of the cycle of overproduction and overconsumption?

Fashion Victim: The Planet

The apparel industry is the biggest polluter after oil, yet overconsumption runs rampant in this sector with the rise and dominance of fast fashion. The appetite for affordable, runway-to-retail garments has dramatically reduced the duration of fashion cycles, and the result is that many items end up in landfills, emitting toxic chemicals that contaminate our soil and groundwater.

Photo by Kris Atomic via Unsplash

Photo by Emmet via Pexels

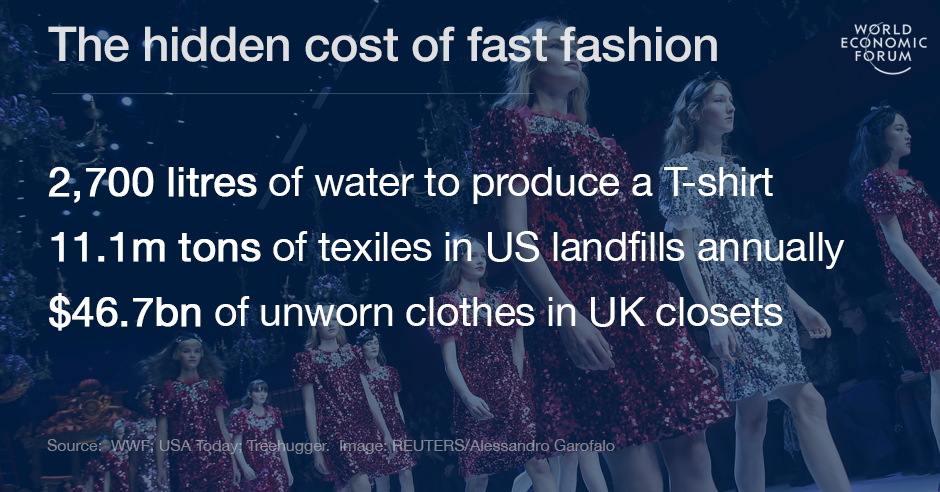

The numbers are staggering, too. The average consumer today buys 60 per cent more clothes compared to the early 2000s, but keeps each garment for only half as long. A single T-shirt takes approximately 2,700 litres of water to produce, so one can only imagine the impact of clothing production on what’s considered as one of the top five global risks: water scarcity. Additionally, polyester production for textiles in 2015 alone contributed to the release of 706 billion kg worth of greenhouse gases; that’s the equivalent of the annual emission of 185 coal-fired power plants.

Slaves to Fashion (Literally)

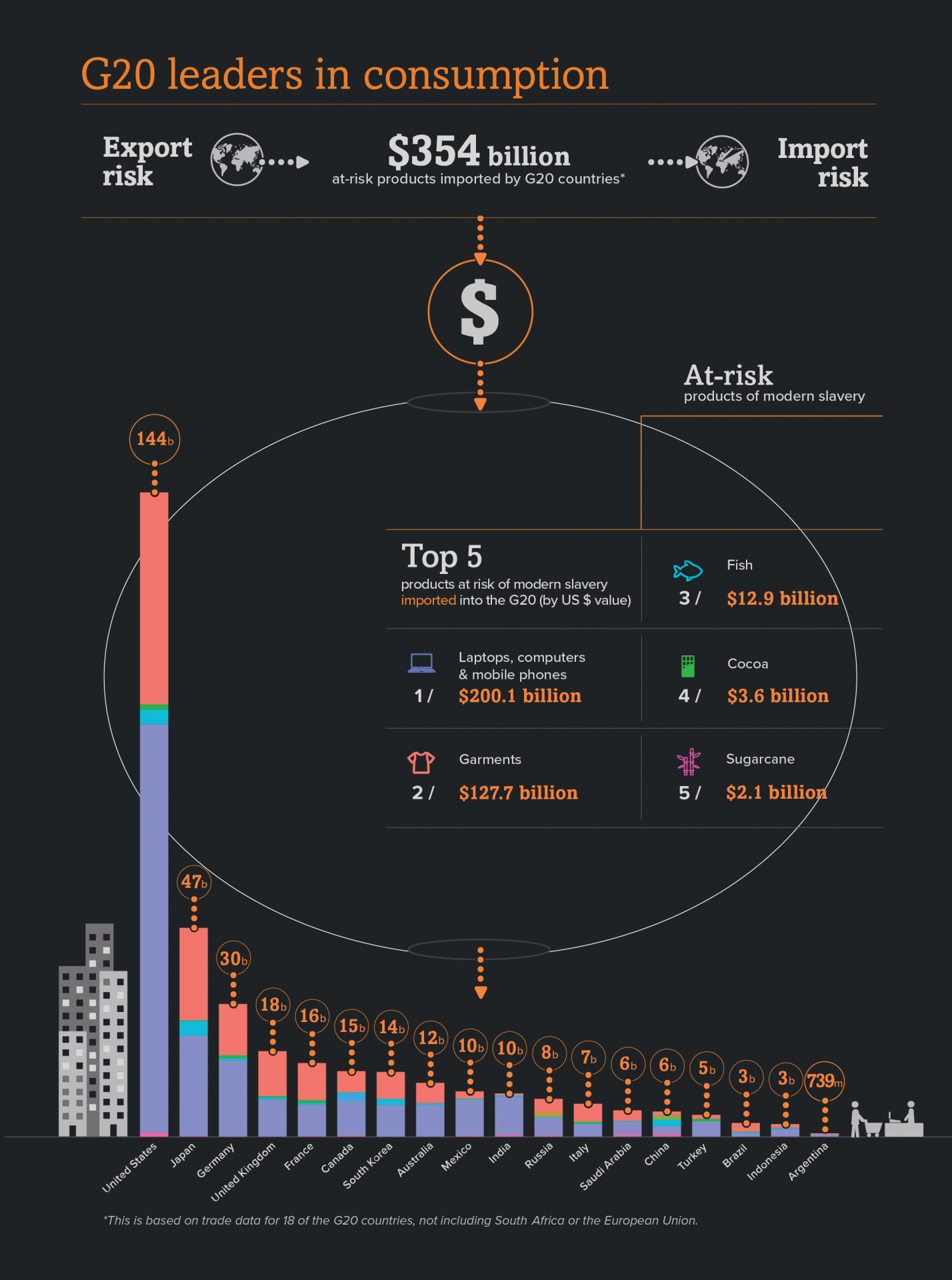

Fast fashion and an increasingly saturated market have also triggered a race to the bottom, as companies feel compelled to find ever-cheaper sources of labour to make up for declining margins. In countries such as India, Thailand or China—home to the most textile and garment factories—such cheap labour comes at the expense of basic workplace rights and protection. According to Walk Free Foundation’s 2018 Global Slavery Index, fashion is among the top five industries most exposed to slavery and forced labour. Clothing products, which are at risk of being produced by victims of slavery, amount to US$127.7 billion in value, the second largest category of imports in the G20 countries after electronics.

In many cases, women, men and children from impoverished rural areas are trapped into joining textile factories under the false promise of decent pay, housing and schooling, but end up working with no benefits and under precarious conditions, at worksites fraught with injuries and deaths. Child labour is particularly prevalent in the garment industry because children are viewed as obedient workers who rarely speak up, and because much of the production requires low-skilled labour and tasks that are often better suited to children than adults. In cotton picking, for instance, employers prefer to hire children for their small fingers, which do not damage the crop. “I was in Delhi two years ago interviewing children who’d been in situations of forced labour and modern slavery in factories,” shared Grace Forrest, Walk Free Foundation’s Founding Director, in an interview with Vogue Australia. Forrest described how one of the children she interviewed, a nine-year-old boy, was lured into a garment factory under the pretext of being able to go to school, but ended up being held there for two years, stitching clothes for a manufacturer whose stores can be found all over New York City. “If you look closely at his hands, you can see the scars … from being beaten with scissors when there was a malfunction with the machine.”

Branded Good

While it will take more time and long-term commitment from stakeholders—both manufacturers and consumers—to overhaul the fashion business, the ground is shifting. The watershed moment came in the 1990s, when the appalling conditions of Nike’s Asian factories were exposed. After that public revelation, brands could no longer close their eyes to practices of slavery in their supply chains and had to introduce stringent due diligence and audit processes at every step of production.

Photo by Alexandra Gorn via Unsplash

Photo by Terje Sollie via Pexels

Today, the need for change is ever more urgent, with climate change issues and water crises looming large. As such, sustainability has been placed front and centre of the fashion industry’s agenda. Countless celebrities have become advocates for sustainable fashion, while mass market brands have introduced innovative product lines; take, for instance, Adidas’ shoes made out of recycled ocean plastic, or Girlfriend Collective’s leggings produced from recycled fishing nets. Yet looking at figures released by the Global Slavery Index and cases like the 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, it’s obvious we have a long way to go. Many people remain sceptical about fashion’s ability to ever become ethical and/or sustainable, while others wonder if brands are simply exploiting the latest industry buzzwords as marketing ploys. Only time will tell. As the pressure mounts on labels to be more socially responsible and transparent about their businesses and manufacturing processes, we are also witnessing a new wave of fashion social enterprises. With their emergence come innovations in production practices, such as upcycling, and new ways to empower vulnerable communities through fashion. If these socially minded businesses have the savvy and support to grow and thrive, they may just lead the “fashion revolution”.

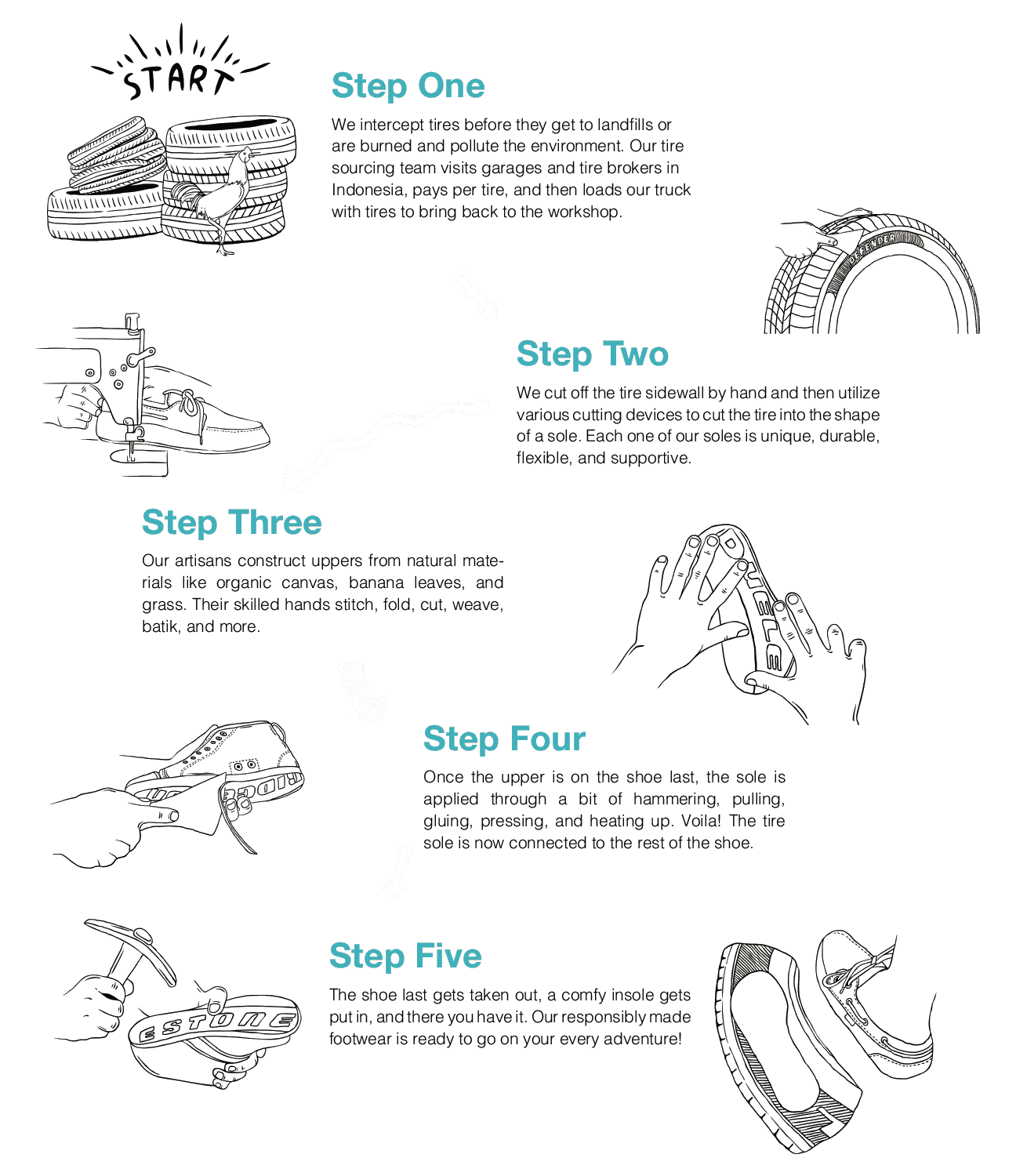

Tyred of Walking

Tyre waste amounts to a staggering US$1.5 billion every year and takes thousands of years to decompose. In tropical countries, the disposed wheels often become a breeding ground for mosquitoes, leading to the spread of diseases like malaria and dengue fever. Often used as a substitute for fuel, tyres emit toxic oil and fumes when burned, and can catch fire during lightning storms, posing a serious hazard for humans and the environment alike. During Kyle Parsons’ first trip to Bali, he came to know more about the devastating environmental impact of tyre waste when he purchased a pair of sandals made out of motorcycle tyres. This led Parsons to found Indosole, which repurposes discarded tyres to create some of the world’s most durable footwear. The certified B Corp uses a toxic-free manufacturing process and no powered machinery—soles are made of tyre cut-outs, while the uppers are constructed from natural materials such as organic canvas, grass or banana leaves.

Source: Indosole

"So far, Indosole has prevented over 100,000 waste tyres from reaching landfills, giving them a new life as soles for our footwear. We have provided jobs to many Indonesian craftspeople as well as educational programmes on recycling to the country’s youth. Our goal is to use the most thoughtful processes and materials for our products while empowering our customers to make more conscious choices in their daily lives.” —Kyle Parsons, Founder and President of Indosole

Cup of Tee

Did you know that your morning cup of joe uses only 0.2 per cent of the coffee beans involved in its preparation? The remaining 99.8 per cent turns into coffee grounds, usually bound for the trash. To tackle the devastating environmental impact of coffee, a Taiwanese clothing manufacturer introduced a clothing line that’s made out of coffee waste. S.Caf é was founded by Jason Chen, CEO of textile-maker Singtex, after his wife made a passing joke about how coffee could eliminate body odour and absorb sweat. After four years of research, Chen became the world’s first garment manufacturer to turn coffee waste into fabric.

Photo by Tyler Nix on Unsplash

S.Café gathers residual coffee grounds from coffee places and stores such as Starbucks and 7-11 as its raw materials. The polyester manufactured from recycled PET bottles is then mixed with roasted coffee grounds to create coffee yarn and eventually clothing fabric. (Three cups of coffee grounds and five plastic bottles can produce one T-shirt.) Besides being an environmentally friendly alternative to water-intensive cotton, the coffee-laced materials from S.Café also have odour-control properties, are quick-drying and UV proof.

“It took us four years of extensive research and an investment of US$1.7 million to launch S.Café. We work with over 110 clients including major brands such as North Face, Hugo Boss or Victoria’s Secret. Importantly, our coffee-to-fabric model can be replicated worldwide as a means for coffee-producing communities to earn extra income and improve their livelihoods.” —Jason Chen, Founder and President of S.Café

Chen has also partnered with Café Buendía in Colombia to extract coffee oil and use the leftover solids to create fabric, which can then be sold to the local market by the farmers who own the coffee shops. In the past, Café Buendía would incinerate up to 25 tons of coffee grounds per day, but with Chen’s help, it has successfully monetised coffee waste, something that previously had no value. More recently, as part of the 2018 Earth Day campaign, S.Café teamed up with Starbucks in Indonesia and Taiwan to sell polo shirts and candles made out of recycled coffee grounds for charity.

Sew Far, Sew Good

From empowering refugee children in Malaysia to training marginalised women in Nepal and India and supporting at-risk pregnant girls in Singapore, social ventures that leverage fashion to uplift vulnerable communities abound. Sowing Room teaches abused and underprivileged women how to sew lifestyle and household accessories using upcycled fabrics. Raw materials include off-cuts, textile scraps and sample swatches of designer fabrics donated by textile merchants—all of which would otherwise end up in landfills—and are repurposed into totes, evening clutches, cosmetic pouches, table napkins, table runners and straw sleeves.

Photo by Roman Spiridonov on Unsplash

“The ladies feel like they are discards. But beauty can be brought out of castaways,” shared Jolene Teo, its founder, who merged her skills in business, jewellery and floral design with her experience in counselling victims of domestic violence to create Sowing Room. Her employees are at-risk women with little formal education and who live in shelters, so learning a new skill is a way for them to heal, earn an income, and—in some cases—start their own business after returning to their home countries in the Philippines, Myanmar or India. Sowing Room sells their designs online, at pop-up stores and in socially minded F&B outlets. The ladies are paid a fair wage for each piece of product they produced. Two of Sowing Room’s trainees, Jeanie from the Philippines and Manpreet from India, spent several months with the social enterprise before returning to their home countries. Teo gave them a sewing machine each as parting gifts, and both women are now proud owners of their own small businesses.

“Before when I was broke, I was just broke. Now when I’m broke, I know I can create something to sell.” —Jeanie, Sowing Room trainee

The Fashion Revolution Starts with YOU

Photo via Pexels

Most shoppers want to be in sync with the latest trends, and not many know enough about ethical and eco-friendly labels—are the pieces frumpy and expensive? But as the industry undergoes a revolution of sorts, consumer attitudes need to change as well. More than ever, customers need to put aside preconceived notions, reconsider their taste for quick-and-cheap fashion, and invest in sustainable and ethical wardrobe staples.

Here are five easy ways to become a socially responsible fashionista#1 Go local, be savvy: Besides supporting local designers, take advantage of the practical tools available, including barcode-scanning apps or a downloadable plug-in, to help you determine if your favourite brands have any traces of slavery or animal cruelty in their supply chains. The Good On You app, for instance, ranks fashion brands according to their environmental and social impact, helps you identify and unlock deals with companies that rank high in terms of ethics and sustainability, and allows you to advocate for change with labels that fare weakly in their Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) footprint.

#2 Less is more: Be more selective in your clothing choices, prioritising quality over quantity. Apply the #30wears test, a campaign started by Livia Firth to encourage slow fashion and more conscious consumer choices. Consider if the item will last you 30 washes, if you’ll wear it at least 30 times, if it’s a high-quality piece, and if you’ll still want to wear it in six months’ or a year’s time. If the answer is “no” to any of these questions, refrain from making a purchase.

#3 Declutter and donate: Apply the “1-in-1-out” rule for every piece of clothing or accessory you buy: schedule a yearly (at least) closet audit, and while you declutter make sure to donate pre-loved items to charity instead of dumping them in the trash. There are numerous locations in Singapore where you can drop off your unwanted clothes (and other household items) to support those in need. Beneficiaries include migrant workers, victims of domestic violence, people with disabilities and low-income families.

#4 Go for seconds: The iconic TV series Sex and the City transformed the way we consume fashion, and among the countless trends the show introduced, it made vintage clothing stylish. Buying second-hand clothing is not only chic, but also helps you save money and be kind to the environment. There are numerous second-hand outlets in Singapore, such as Refash, a large fashion re-commerce platform selling pre-loved clothing both online and at physical stores, as well as other affordable thrift and consignment shops.

#5 Rated R-R-R: Support labels that reuse, reduce and recycle. The sky’s the limit in terms of product range: you can find everything from swimwear made out of seaweed, to outdoor clothing produced from plastic soda bottles—you only have to look. Connected Threads Asia, an organisation promoting sustainable fashion, published a comprehensive list of sustainable fashion brands in Singapore, including labels that use upcycled and recycled materials. If you have a taste for high-end fashion, there are sustainable options too. Finally, for those who like a good crafting project, consider attending tutorials and workshops by Repair Kopitiam and Agy Textile Artist on how to repair, upcycle and salvage pre-loved clothing.

|

Based out of Singapore and Indonesia, Trang Chu Minh is in charge of editorial content and strategy for Causeartist in Asia, leading the media platform’s expansion in the region. In addition to her role at Causeartist, she divides her time between content and marketing strategy at Refinitiv (formerly Thomson Reuters Financial & Risk), as a freelance contributor to publications focused on social and environmental issues, and as a consultant on international development projects on topics ranging from sustainable development to education and women’s rights. She can be reached at Trang.ChuMinh@causeartist.com |

Comments