By Chong Ning Qian

In an inclusive society, all women would have equal opportunities as men to participate socially, politically and economically. They would be valued and recognised as individuals in their own right and not primarily defined by their marital and reproductive status. Has this been achieved in Singapore? Contrary to common belief, the nation still has some ways to go in this regard, for significant groups of women in Singapore continue to be marginalised and disadvantaged.

Women, "Family" and Caregiving

Stereotypes about females are shaped largely in relation to their roles in the family, particularly the heterosexual nuclear family which is historically underpinned by a set of unequal gender relations and reproduces a gendered division of labour. Women were and are still largely the primary caregivers while men are the primary breadwinners.

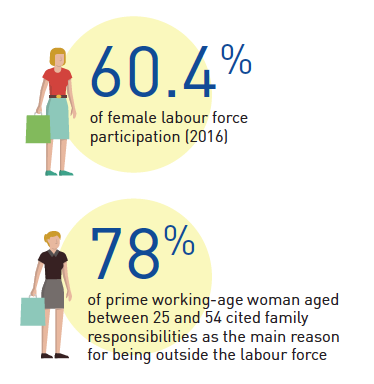

Despite increasing levels of education among Singaporean women, the female labour force participation (60.4 per cent in 2016) is low compared to other OECD countries.1 Females form 64 per cent of residents outside the labour force, and 78 per cent of prime working-age women aged 25 to 54 cite family responsibilities as the main reason for being outside the labour force. These women generally do not return after leaving the labour force, resulting in the lack of an “M” curve for female labour force participation rate.2

For countries with an “M” curve, such as Japan and South Korea, women leave the labour force in their childbearing years (forming the first downward curve), but they return to work after a number of years before dropping out again in old age (thus forming the second curve). Women’s inclusion in the economy at all levels is affected by the gendered division of labour— from being unable to enter paid employment in the first place, to having to compromise on career advancements because of inadequate support in fulfilling their caregiving responsibilities.

Treating caregiving and household responsibilities as “women’s work” is particularly problematic because such work is grossly undervalued. Women are expected to carry out these tasks without compensation or protection of their financial security, because it is seen as their “natural” duty to do so. The undervaluation of “women’s work” and the gender gap in caregiving and the workplace have significant repercussions on women’s financial security, particularly in old age, since they have fewer opportunities to accumulate resources during their prime working ages.

There is a need to reduce the burden on women from having to choose between paid employment and caregiving, and this can happen in the following ways: equalising responsibilities between genders; greater state provision of caregiving services; better support for informal family caregivers; and policies to help working adults better manage paid employment and caregiving. Suggestions to financially compensate family caregivers or for greater state involvement in providing care services are sometimes regarded as undermining traditional values of filial piety and family relations.

These fears, however, are unsubstantiated. Instead, there is evidence that with more state provision and support in caregiving, the total quantity of care received increases, and the emotional closeness of the relations between generations in the family is not negatively affected.3

Single Mothers

Stereotyping of women also means that their role as mothers is only recognised and valued in the context of the heterosexual, nuclear family. For example, access to certain public resources, notably housing, is tied to marital status; and women who are single parents—who also form the bulk of single parents—face discriminatory policies that do not recognise their needs and rights as mothers. A 2016 AWARE study found that single mothers, particularly low-income ones, have trouble accessing public housing.4 Several restrictions also disadvantage divorced mothers in particular: unless they have full care and control of all their children, divorcees are barred from renting from the Housing and Development Board (HDB)—the state provider of public housing in Singapore—for three months, and from purchase of subsidised housing for three years after the disposal of their matrimonial flat. This pushes them into the costly open rental market or into staying with other family members. As a result, they experience frequent moves, overcrowding and extra pressure from having to deal with the instability of their housing arrangements, on top of having to be both the sole caregiver and breadwinner.

In recent years, there have been moves to equalise the treatment of mothers, such as granting all mothers entitlement to the full 16-week paid maternity leave. However, women who have children outside of marriage, as well as their children, continue to be disadvantaged in some legal and policy areas. The offspring of unwed mothers, considered “illegitimate”, are unable to make inheritance claims from their biological fathers, and are able to inherit from their mother’s estate (absent a will) only if the mother does not otherwise have legitimate children.

Further, unmarried mothers do not qualify for tax reliefs that other married, working mothers are entitled to. Under public housing policies, unwed mothers and their children are not recognised as a family nucleus, greatly limiting their housing options. Single mothers also face stigma, moral policing and judgement. Unmarried mothers I have spoken to expressed that they often felt singled out and shamed when interacting with government agencies. One was embarrassed when the officer attending to her repeatedly exclaimed, “I don’t know what to do about your case. I don’t know how to key into the system. In my 20 years here, I have never come across a case like yours.” Another had asked an officer why unmarried mothers do not get tax reliefs, and received this reply: “Many unwed mothers already don’t earn enough, so they don’t need (the tax relief).” When the same lady continued to question the discriminatory policies, the officer said, "That’s your choice. You wanted to give birth."

On the Ministry of Social and Family Development’s website, we can read Nominated Member of Parliament Mr Kok Heng Leun’s parliamentary questions to the Minister for Social and Family Development, namely:

- Which are the areas in law, policy and decision-making by Government agencies and schools, that make a distinction between ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ children; and

- What are the differences in outcomes for ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ children and their parents in each of these areas?5

To which the Minister replied that “Government benefits that support the growth and development of children are given to all Singaporean children, regardless of their legitimacy status.” However, his concluding words were:

Where benefits or laws differentiate on legitimacy status, they reflect the Government’s desire to promote strong marriages. Parenthood within marriage is the desired and prevailing social norm, which we want to continue to promote as this is key to having strong families.6

However, notwithstanding the state’s desire to promote what it describes as “desired and prevailing social norms” (though these are contested) through differential treatment in policies, a society that truly respects the rights of women should not make them secondary to ideology—in this case, the ideology of what makes a family and what women’s roles ought to be.

What Needs to be Done?

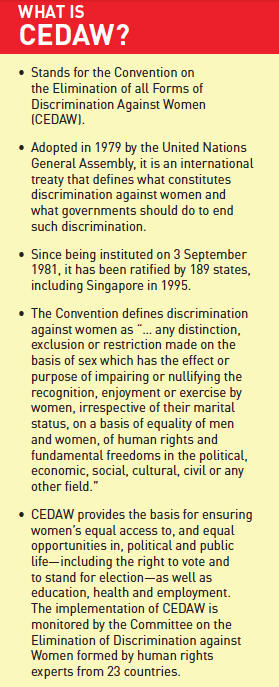

Having ratified the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1995, Singapore is obliged to ensure that women have equal access to opportunities in areas such as employment, healthcare, education and politics.

CEDAW is a powerful instrument for citizens and residents to hold states accountable to its commitment to gender equality. The Singapore government is to provide periodic updates to the CEDAW committee on its progress, while non-governmental groups are also encouraged to send a Shadow Report to give a more comprehensive picture of the situation.

This year, AWARE is part of a coalition of NGOs that will submit the Shadow Report and answer to the committee in Geneva. The issues of gender stereotyping, unequal division of responsibilities between genders in the family, undervaluation of women’s work and discrimination on the basis of other factors affecting women identified here are all in violation of CEDAW principles. The sort of thinking that these policies embody goes beyond these specific areas, however, and informs the approach of decision-makers in every field of policy and society. A more coordinated and dedicated response from the government is thus needed to ensure the fundamental issue of gender inequality is systematically addressed in every arena and at every level.

To this end, it is important to note that we are missing the necessary, formal structures to at least recognise and define discrimination and gender equality. At the highest level, Singapore’s Constitution does not prohibit discrimination based on sex or gender. The highest court has stated that the Constitution forbids only discrimination on grounds listed explicitly in Article 12(2) thereof: “religion, race, descent, or place of birth”. Formal equality before the law under Article 12(1) may apply regardless of sex or gender, but it is not equivalent to a substantive guarantee of non-discrimination on the basis of sex or gender. In other words, there is no formal protection from discrimination on the basis of sex or gender under the Constitution of Singapore. This is contrary to Article 1(a) of CEDAW, which states that the principle of equality of men and women must be embodied in the national constitution or other relevant legislation.

Second, the Office for Women’s Development and Inter-Ministry Committee for CEDAW is tasked with monitoring and implementing the instruments of CEDAW. However, it is unclear as to what their activities are in such implementation. Apart from making the periodic reports to the CEDAW committee, is there meaningful and consistent engagement with NGOs and the public on the formation of their agenda and activities? What groundwork have these groups undertaken in order to understand the everyday situations of women in Singapore, and to apply a consistent gender equality lens to policy formulation in all areas?

Third, Singapore has yet to fully withdraw its reservation to Article 2, the core provision of CEDAW which calls on state parties to condemn discrimination against women in all its forms. Discrimination on the basis of gender or sex is closely tied to other forms of discrimination and inequality. Particular attention needs to be paid to how women are marginalised because of their marital status, sexual orientation, nationality, class and so on. Gender equality is not achieved if only select groups of women get to experience it.

Women’s political, economic and social status are currently not equal to those of men, and this is not justifiable. Their opportunities are limited in a way that men’s are not. Gender stereotyping continues to perpetuate the idea that some tasks belong to females, and others to males. The work associated with and overwhelmingly carried out by women is systematically undervalued, contributing significantly to the status quo. True commitment to gender equality requires the state to respect women as individuals in their own right, free of discrimination on the basis of their sex or other factors. Women should not be primarily defined by their marital and reproductive status, or be denied access to certain rights and benefits as a result.

The community, civil society and individuals each play important roles in the fight for gender equality. The state, however, is in a unique and powerful position to take the lead in this. It has the power to educate and reshape an entire generation’s perceptions of gender, to enact laws and policies to end discrimination and meaningfully push for the inclusiveness of women in every arena. It has been more than two decades since Singapore ratified CEDAW, and it is time for Singapore to make good on its commitment.

Notes

1 Ministry of Manpower, “2016 Labour Force Survey Highlights”, at http://stats.mom.gov.sg/iMAS_PdfLibrary/mrsd_2016LabourForce_ survey_highlights.pdf

2 Ministry of Manpower, “Speech by Minister Lim Swee Say in Response to Motion on Aspirations of Singaporean Women in Parliament”, 6 April 2017, at http://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/ speeches/2017/0405-speech-by-minister-mr-lim-swee-say-in-response-to-motion-on-aspirations-of-singaporean-women-in-parliament

3 Anna Whitaker, “Family Involvement in the Institutional Eldercare Context:. Towards a New Understanding”, Journal of Aging Studies 23, 3 (2009): 158–67; Andreas Motel-Klingebiel, Clemens Tesch-Roemer and Hans-Joachim Von Kondratowitz, “Welfare States Do Not Crowd Out the Family: Evidence For Mixed Responsibility from Comparative Analyses”, Ageing & Society 25, 6 (2005): 863–82.

4 AWARE, “Single Parents’ Access to Public Housing: Findings from AWARE’s Research Project”, December 2016, at http://d2t1lspzrjtif2. cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/Single-Parents-Access-to-Public- Housing.-Final-version..pdf

5 Ministry of Social and Family Development, “Legal and Policy Distinction between Legitimate and Illegitimate Children”, 13 September 2016, at https://www.msf.gov.sg/media-room/Pages/Legal-and-policy-distinction-between-legitimate-and-illegitimate-children.aspx

6 Ibid.

|

Chong Ning Qian is a Research Executive at the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE), Singapore’s leading gender equality advocacy group. AWARE carries out research into various issues affecting women, including single parents’ access to housing, low-income women’s decisions about caregiving and paid work, and Singapore's compliance with CEDAW's standards. Ning Qian graduated with a B.Soc.Sci. (Hon.) in Sociology from the National University of Singapore. She can be reached at advocacy@aware.org.sg |

Comments