By Do Youn Lee

Reading about foreign domestic workers (FDWs) in Singapore, we tend to glean the insights of academics and journalists rather than the FDWs themselves. But when reports and articles frame the FDW community and their experiences within a wider discussion of society, households and systems, the individuals and their stories can sometimes get lost within the narrative. Therefore, this edition of #Spotlight celebrates the unique voices of five foreign domestic workers in Singapore. What are their motivations and passions? How do they like to unwind outside work? What specific challenges do they face? How are they taking care of themselves and forging new friendships in a foreign land? These questions, and more, were on my mind as I set out to get to know the women behind the job. Where possible, I have attempted to provide the ladies' photographs, full names, ages, nationality, and years of FDW experience. However, I have not reflected the data in every instance due to individual requests for privacy or other personal reasons. I am grateful to Aidha and HOME for their kind assistance in facilitating interviews for this article.

Endah Purnamasari (Indonesian, 33, 14 years as an FDW)

After working as a domestic helper in Jakarta for four years, I realised I wasn’t earning enough to support my family. So in 2009, I came to Singapore to work as an FDW. I was very young then, and arrived with many hopes and dreams. But my first six years here were marked by much hardship. My first employer treated me extremely badly. I lived with three families in one HDB unit, looking after 17 people, out of whom 9 were kids. Because this employer didn’t appreciate how difficult it was for me to be away from my own home and family, or care that I might crave friendships and connections, I wasn’t allowed to have days off for two entire years. I was most disappointed when I asked for permission to study at the Singapore Indonesian School and my employer forbade it. Eventually, however, I did get to attend classes there on Sundays, but only because the Indonesian government mandated days off for Indonesian FDWs. Even then, I never got to have a proper rest day: I was only allowed to leave the house after I’d finished my chores, so I’d be late for my classes every single time. And upon my return, my employer made me work till after midnight. Despite everything, I carried on for six years, thinking I could survive as long as nobody hit me. Finally, when things became too difficult, I asked for a change of employers. I told her firmly that I’d completed my contract, and refused to change my mind even though she threatened me. With my present employers, I'm in a much more comfortable environment. Unlike the previous time, they treat me like a human being, respect my privacy and are supportive of my studies. I'm currently at senior high school level, in addition to taking financial management courses at Aidha and cooking classes at the Expat Kitchen. Today, I’m happy to share that I’ve saved enough money from my 10 years of hard work to purchase 2,000 square meters of land back in Indonesia. For me, success isn’t so much about how good your English is, or your outward appearance. It’s also about thinking smart and working hard.

Renelyn Tolones Fuentes (Filipina, 33, 8 years as an FDW)

I believe one shouldn’t limit themselves with “goals”. It’s more important to live your life and do all the things that make you happy. If you don’t have any specific dreams or ambitions, then strive to do the best at whatever you’re doing. My life in the Philippines was hard. So when an agency asked me if I wanted to work abroad, I immediately accepted the offer to work as an FDW in Singapore. Upon arriving here, my first impression was the hustle and bustle of city life. It’s such a stark contrast to the part of Philippines where I’m from, which has fewer buildings and a very peaceful vibe. I was thus quite homesick initially, but over time I got used to the feeling. I’ve been living in Singapore for eight years now. My main responsibility is to look after my employer’s children, and in my downtime, I enjoy photography and painting. Some FDWs like to go clubbing on their days off, but I prefer to be out in nature. I like to meet up with my friends and take pictures of scenery. Last week, we went to Jurong Lake Gardens. No matter what happens, I always remind myself to do what I love and to stay motivated.

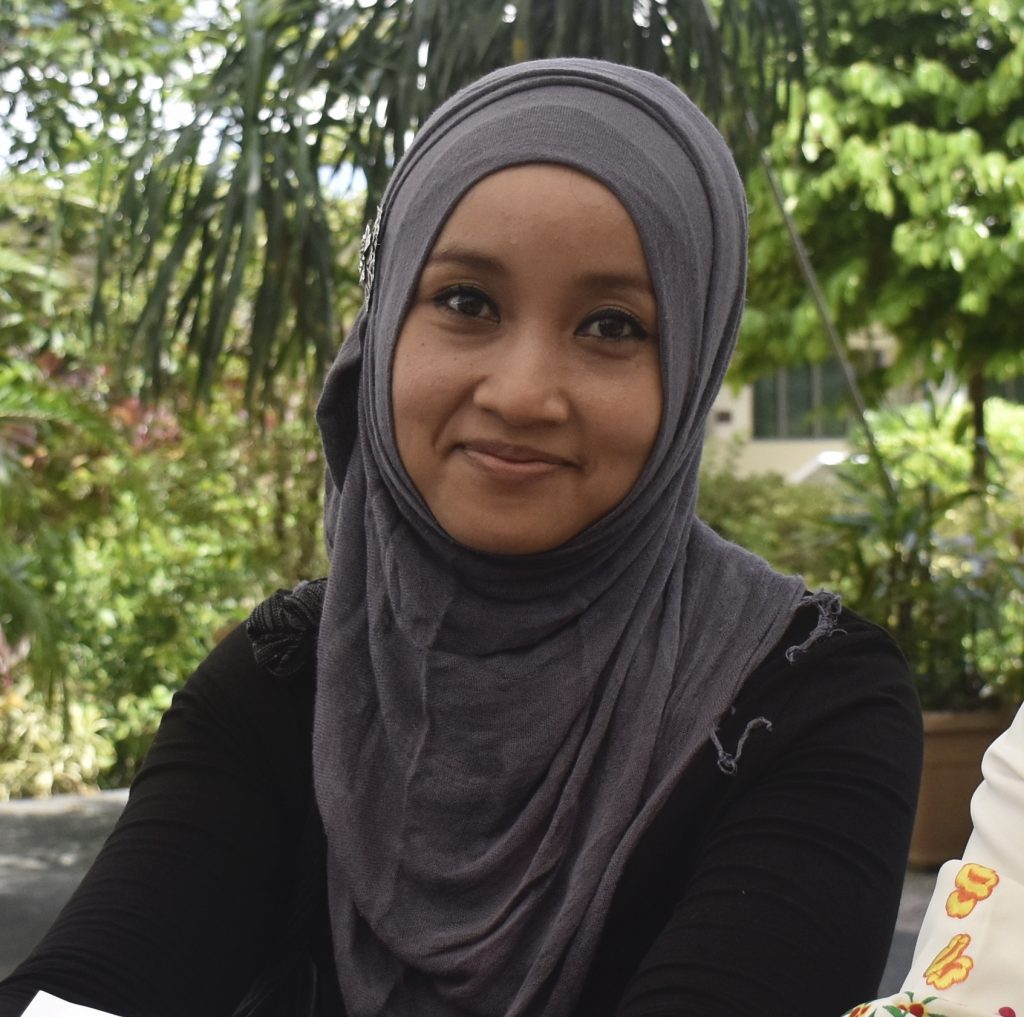

Indah Kurniawati (Indonesian)

My father didn't have enough money to send me to college so he made me get married. Ever since my husband and I got divorced, I've been working as an FDW in Singapore to support my parents and three children back home. Things did not get off to a great start when I arrived. My first employer did not treat me like a human being: I didn’t have any days off or even permission to use the phone. After three months, I was ready to give up, but she persuaded me to stay because she’d already changed maids six times within the same year. To get myself through the challenging times, I’d focus my attention on my employer’s children whom I was looking after, or try to convince myself that I could deal with it all. Eventually, though, I had to stop working for her because of the continued mistreatment. Early on, I learned the importance of being resourceful and finding my own information. Whenever I needed help, I asked the neighbours; through the act of ferrying the employer’s kids to and from their school, I also taught myself how to use public transport. I’m a quick learner, I’d say. In addition to Madurese, Javanese and Bahasa, I picked up English and can now speak it fluently. These days, I’ve started learning Hindi, too. Acquiring language skills and familiarising myself with the local public transportation system are the things that have helped me adjust to life in another country. Things are now much better at my present employer's. I have set working hours, get to visit my family in Indonesia twice a year, and have the opportunity to pursue a degree in Business Administration. Someday I hope to manage my own property.

Every now and then, though, I still think about my past experience and empathise with some of my FDW friends who have difficulties with their respective employers.

Many FDWs still don’t get days off and aren’t permitted to step outside the doors of their employer’s residence. In those cases, your workplace is not so different from a prison. Some employers even withhold their helpers’ monthly salaries under the pretext of safeguarding the money for them, but everyone has the right to receive their wages on time, and not bear the risk of being unpaid. It’s so important to appreciate the work of FDWs; without us, employers can’t be productive. We don’t ask for a lot: just say “thank you” and let us rest.

I encourage all foreign domestic workers to read up online, find a supportive network of friends, and know how to reach out if in need. There is an active Singapore-based FDW community on Facebook, which is a great resource for information. Ultimately, though, it’s important to have a positive mindset: in any challenging situation, don’t give up. There can be no success without patience—that’s the thinking that got me through the tough times.

Retno Nawangsih (Indonesian, 10 years as an FDW)

When I graduated from high school, I had many hopes and aspirations. I wanted to get a university degree, work in an office and ultimately “do something good”. However, in the real world not everything goes according to plan. After one year of job-hunting in Jakarta, I decided to work as an FDW in Singapore. Ten years on, I am still in this role. The job can get boring because you’re doing the same thing every day, but I enjoy my days off and my salary is good. In comparison to other FDWs who have difficult relationships with their employers, I consider myself to be lucky. When I first came to Singapore, it wasn’t an easy transition. The language barrier between my employer and I caused many conflicts and misunderstandings, even though I tried hard to understand what they wanted from me. In spite of all that, I never stopped believing that if you have a strong will and think positively about others, you can overcome anything—even language and cultural differences. For self-improvement, I took up English courses. Balancing work and study, while paying for my classes, was difficult. However, I successfully completed my English courses and leveraged my newly acquired skills to further my education. I am now pursuing a diploma in Accounting. On my days off, I read books and draw. I’m passionate about literature and art, so I dream of opening a stationery shop one day. I also hope to learn how to save enough money to achieve my ultimate goal of buying a house in Indonesia.

Novia (Indonesian, 42, 14 years as an FDW)

I am a single mother with two children, working as an FDW in Singapore. I love to help others, so on my days off, I volunteer as a counsellor for HOME’s helpdesk team. In Indonesia, people like me—who come from villages and engage in domestic work—are often treated as members of a lower class. Still, I've never let my level of education or circumstances affect my determination to make a positive change. I really believe that anyone can make a difference in society, and that we should all find a way to help each other out. In my counselling work, FDWs sometimes address me as “Madam”, but I’d explain that I’m an FDW just like them. This puts them at ease and makes them more comfortable to share their feelings. Having volunteered as a counsellor for over four years now, it’s easy for me to understand how others feel. FDWs face very real struggles—such as unpaid wages and a lack of food—and these can really take a toll on their mental health. So in any situation, I’d never try to trivialise a problem or tell them to “just get over it”. In cases of employer abuse, I first try to fully understand the situation and then offer the relevant information about rules and regulations in place. I may not be able to knock on their employer’s door to demand justice—that would cost the FDW their job—but I can listen attentively and provide useful information. The rest is up to them. Working for this many years as an FDW and volunteer counsellor, I have a few observations.

In my view, some common issues can be avoided if foreign domestic workers are given enough information about their contract terms and legal rights, or if these are explained to them carefully at the outset. However, many FDWs today are still signing contracts without knowing they can opt for a weekly day off or receive extra compensation. As a result, they find themselves working every day of the week, and never get to leave their employer’s house, make new friends, or have anybody to talk to and share their problems with. Therefore, it is very important for FDWs to empower themselves with all the knowledge out there and know exactly what they’re signing up for.

Nonetheless, some factors are simply out of the FDW’s control. For example, when your employer hasn’t paid you for many months and you’re forced to break your contract. On that note, I hope governments can take more action to safeguard FDW welfare and discipline errant employers where necessary. That’s not to say foreign domestic workers should sit around and wait for the authorities to take action—we can all speak up, raise awareness, and do what’s possible within our capacity.

Banner image by Kyle Arcilla via Unsplash.

|

Do Youn Lee was a 2019 Summer Associate (Editorial) at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation. She is a rising senior at Yale-NUS College, majoring in Global Affairs and minoring in Philosophy. Do Youn spent most of her years in Korea, where she learned Spanish and was an avid lacrosse player. With an interest in youth empowerment, she worked as a programme management intern at the ASEAN Foundation and as a board member at the International Association for Political Science Students. Do Youn presently runs the Yale-NUS Chamber Music Collective, where she plays the violin and organises concerts every semester. She can be reached at doyoun@u.yale-nus.edu.sg |

Comments