By R Chandran

Tears started to trickle down my cheeks. I knew it would happen and had steeled myself against it. Yet in that moment I couldn’t, or more like, didn’t want to stop the flow. Keith (not his real name) was playing a solo piece on the grand piano. This young man was delivering a flawless performance in front of an 800-strong audience who watched, captivated. Following his solo, he played the accompaniment for a professional jazz singer crooning Ella Fitzgerald’s Summer Time. Keith is in his twenties and lives with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Prior to his performance, many had doubts about his ability to control himself onstage, or act and play the piano in front of a live crowd. His was the central character in an 80-minute musical drama. What if he had a meltdown?

Early Years (1980s–2000s)

When I was a child, my special ability was in sports. I was good at football, badminton and sprinting, and even had aspirations of being a professional sportsman when I grew up. However, in terms of pursuing a sustainable sporting career, I was ahead of my time by a few generations. I had other interests, too—I thought I might become a writer since I enjoy words and like putting them down on paper. Young and shy, writing was a way to express myself, and I enjoyed a confidence boost every time my essays were read out loud to the class. Soon after, I discovered my passion for theatre, which turned into a lifelong career.

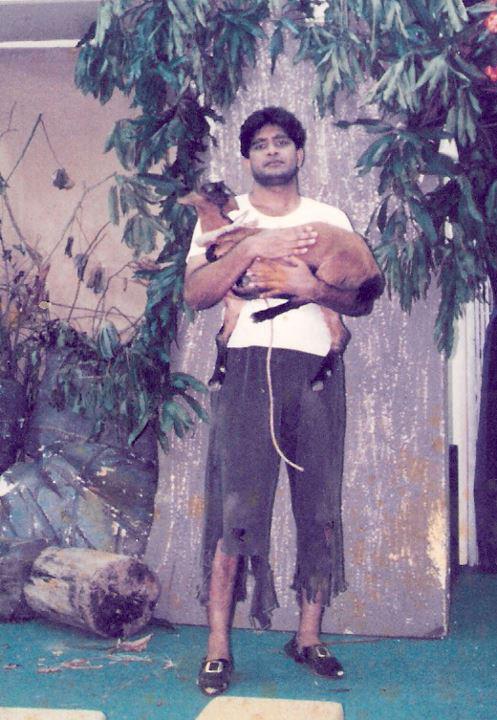

In 1985, a younger Chandran played Robinson Crusoe with a goat as his co-actor.

In the early 1980s, Singapore’s theatre scene was tagged with an amateur status, and children’s theatre was basically non-existent. But on 1 July 1984, I started ACT 3 Theatrics with two friends, Jasmin Samat Simon and Ruby Lim-Yang. As the country’s first professional theatre company, we aimed to introduce and develop theatrical performances and drama education for children. My role was, and still is, that of a writer, director, actor and educator. ACT 3 Theatrics began by taking theatre out to people. We travelled around in a beat-up blue van to residential homes, bookshops, shopping centres, housing estates, hotels, schools, parks, and even the beach. The “Living Room Theatre”—what we called our roving stage—offered children, parents and teachers the opportunity to experience the magic of the performing arts and creative self-expression.

Treasure Island, staged in a park, 1983.

Treasure Island, staged in a park, 1983.

Over the course of my career and work-related travels, I’ve worked with many children from all over the world. I’ve witnessed first-hand how they respond to theatre, no matter their cultural background or socio-economic status. Whether we are performing in hi-tech, state-of-the-art auditoriums of metropolitan Tokyo, or on a makeshift stage within a rural Thai village, most students approach theatre with overwhelming enthusiasm, energy and open hearts.

Turning Point (2011–Present)

By 2011, the theatre scene, especially children’s theatre, was thriving in Singapore. A handful of professional companies were staging shows, theatre groups were visiting schools for performances and to conduct drama programmes, and more educational institutions were incorporating drama education into their curriculum. Also around this time, ACT 3 Theatrics gained a new lease of life. After the departure of two of the original directors, actress (also my wife) Amy J. Cheng came onboard as Creative Director, followed by two new partners: businesswoman Marine Lim-Tanasekar and entrepreneur Ameer Jumabhoy (who had been a child actor with us back in the day).

Chandran in a performative storytelling of Attack of the Swordfish, 2017.

Chandran in a performative storytelling of Attack of the Swordfish, 2017.

Chandran with the cast of the "Meet the MP" TV series, for which he was nominated for Best Actor in a Comedy at the 2017 Asian Television Awards.

Chandran with the cast of the "Meet the MP" TV series, for which he was nominated for Best Actor in a Comedy at the 2017 Asian Television Awards.

But in 2012, I took a sabbatical to spend more time at home with our two young sons while Amy completed her Graduate Diploma in Primary Education at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia. It was a productive period for me—I wrote 72 instalments of an international TV animation series, Megaminimals, produced by Neptuno, a company based in Spain. Amy was also finding her stay in Perth a rewarding time: as part of her course, she got to teach at local primary schools, whose cohorts included children with special needs. When she returned to Singapore, we discussed and considered the possibility of broadening ACT 3 Theatrics’ scope to include programmes in SPED (Special Education) schools here. Around this time, whether coincidentally or by divine providence, the National Arts Council reached out to us. They asked if we’d be interested to devise and run a short programme at APSN Tanglin School, which caters to students with mild intellectual disabilities (MID) and mild autism. We grabbed the opportunity without a second thought.

Special New Chapter

From that point, special education became a very important focus of ACT 3 Theatrics. The journey into this space, however, was not without its obstacles. I had embarked on this new chapter, armed with my experience of teaching drama in mainstream schools and what I believed to be a perfectly designed programme. However, I felt like a complete failure during my first few sessions of being in a classroom full of SPED students. Apart from a handful of students, the response of most participants was not what I expected. For the most part, I was dealing with individuals with short attention spans—they were continuously and openly preoccupied with their own thoughts and actions, and some would not even turn to face me throughout my 60-minute lesson.

Chandran presenting "Stories in Art", interactive storytelling performances at the National Gallery Singapore, 2019.

Chandran presenting "Stories in Art", interactive storytelling performances at the National Gallery Singapore, 2019.

Chandran presenting "Stories in Art", interactive storytelling performances at the National Gallery Singapore, 2019.

But there was one particular student who inspired me to recalibrate my teaching methods and overcome these challenges. Jim (not his real name) would wander around the class, unrestrained, while my session was ongoing. He’d stop every now and then to peer out of the window, or doodle on the class whiteboard as he wished. Jim was paying scant attention to what I was saying or doing—or so I thought. Part of my teaching programme involved grouping students into teams and having them devise and present a short-story scenario. Earlier, I’d suggested that the teams come up with a visual scene by drawing on a broad sheet of mahjong paper. For this exercise, Jim proceeded to sketch an elaborate, detailed and colourful scene of a countryside, complete with houses, hills, trees, the sun, clouds and birds. In that moment, I realised something: more than just having special needs, these individuals are blessed with special abilities. I also saw clearly that my role is to help uncover these abilities, and give them the room and opportunity to blossom.

Connecting with Special Education (SPED) Students: Lessons Learned

Wait for them to let you into their world. Some students will readily and wholeheartedly welcome the connection, but for some others the road to acceptance has to be paved with patience and positivity. Learning outcomes are also different: with certain students, the goal is to expand their attention span, sharpen their mental focus, tweak their speech constraints and bolster their motor skills; for some others, we try to pump up their imagination and determination to complete a mission. There is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Take advantage of the small class size. Most SPED school classes include between five and ten students, so it’s good to alternate between addressing the whole class and working with individuals on particular exercises. Doing so ensures no one is left behind.

As with any other child or adult, don't generalise their needs. SPED students each face unique challenges: some have short attention spans or an aversion to loud sounds; others are non-verbal, have limited motor skills or an uneven somatosensory system; certain students cannot cope with the stress of engaging and communicating with others; and then there are those with physical disabilities like deafness or blindness, or who need a wheelchair to get around. Identify what are their perceived obstacles, and circumnavigate the way forward in partnership with them.

Progress takes time, but is possible. I had a SPED student who was non-verbal when we first met, but who spontaneously made a sound after many months, then uttered a word some time later, before attempting to have a verbal conversation with me about two years later. There was also a student who used to run and seek refuge under a table, but now interacts with others and even won a school prize for numeracy. Another, who regularly has aggressive meltdowns, stepped offstage after a performance and proudly announced, with a broad smile, to his teacher (about his role), “I was a doctor today.”

Teach them life skills they can apply outside of the SPED environment. It is important for SPED students to learn how to conduct themselves confidently and mingle with others comfortably in different situations. Gauging personal space, exchanging greetings, reading body language cues, standing in queue, waiting for one’s turn, sitting, standing and walking with confidence, self-grooming, handling job interviews, dining outside the home—these are all abilities most people take for granted. However, empowering SPED students with such skills will go a long way towards helping them be better understood, appreciated and respected in their wider community.

Let’s go back to Keith, whose piano performance I described at the beginning of this article, made me emotional. As much as I was moved by his artistic prowess, my tears also sprang from a deeper place. Seeing Keith shine affirmed my belief that special abilities are ingrained in all of us—whatever our “needs”. Come to think of it, don’t we all have “special needs” of our own? I am painfully shy, especially amongst adults and in social settings—if I could cover myself with Harry Potter’s Cloak of Invisibility, I would. But here’s the thing: if my need is to confidently face an audience of strangers and deliver a convincing performance, then I have also found my ability to do so, as an actor, emcee and trainer. In other words, theatre is what helps me overcome what I perceive to be my limitation. My journey of working with individuals with special needs has therefore taught me this: one’s needs often come with abilities—and very special ones, too.

All images courtesy of R Chandran.

|

R Chandran is Founder-Director of ACT 3 Theatrics, Singapore’s first professional theatre company, and Very Special Theatrics, an inclusive performing company established by ACT 3 Theatrics and Very Special Arts Ltd Singapore. He has worked (and played) professionally as a writer, director and actor for the past 35 years, mostly on stage and sporadically on TV and films. He is also the author of six children’s books and has written newspaper columns. Chandran has received national and international recognition for his dramatization and TV acting prowess—he played the Central Storyteller at the 2016 National Day Parade and was nominated for Best Actor in a Comedy at the 2017 Asian Television Awards. He is presently focused on developing drama programmes and creating theatre with and for the special needs community, as well as mentoring teachers at early childhood institutions and primary schools on the use of drama as a teaching tool. Chandran is married to actress and educator Amy J. Cheng and they have two sons. He can be reached at chandran@act3theatrics.com |

Comments