By Yajing Liu

Looking out to the Yellow Sea and surrounded by mountains, the Rongcheng area of Shandong Province, China is scenic and peaceful. However, this county-level city is known not only for its picturesque beauty, but also for being the site of seaweed houses—traditional homes built from natural seaweed and stones. Inhabited mainly by local fishermen, these structures are a reflection of northern Chinese marine culture and fishery customs.

Ma Lan Jiang village, 2009. Seaweed houses built near the sea.

Rongcheng’s seaweed homes go a long way back in history. The region’s geological and geomorphological conditions form a board of shallow waters, beaches, rich algae and seaweed. Since the Neolithic period, the local people have made crude shelters out of natural seaweed and stones. Then, following the Yuan, Ming and Qing empires, the architecture and building techniques evolved with the development of tools and economic culture. In a typical seaweed house, a roof comprises 250–500 kilogrammes of seaweed (harvested from the seabed at a depth of 5–10 metres). The shape of the roof is like a boat—high, steep and low in the middle—and its walls are made up of rough stones, granite, bricks and yellow mud. This specific kind of roof and stone can keep the house cool in the summer and warm in winter.

Lu Jia, 2011. Building of a seaweed house. The average age of a seaweed house builder is over 60—the building technique will be lost if younger generations do not practise and pass on this skill.

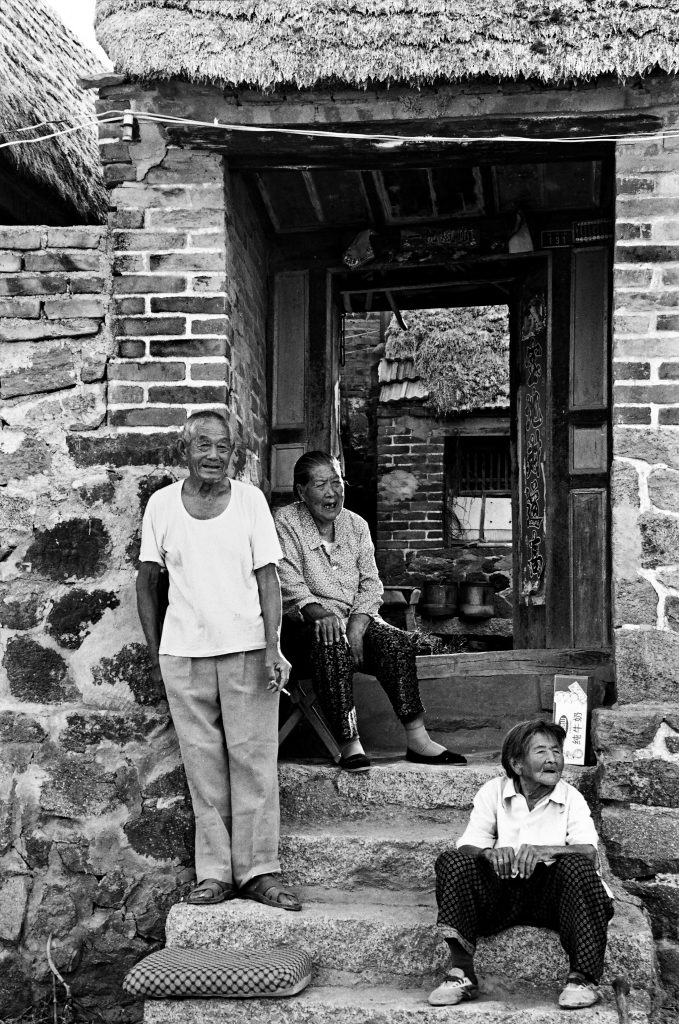

Li Dao, 2009. Team leader Shen Yanquan (foreground) was about 80 years old when this photo was taken.

In the 2000s, these unique dwellings were catalogued within the nation’s famous historical and cultural villages, and the technique of the construction of a seaweed house was named as an intangible cultural heritage of Shandong. However, despite their rich history and culture, many seaweed houses are being demolished in the name of urbanisation and industrialisation. In the last two decades alone, over 80 per cent of these traditional dwellings have disappeared to make way for modern buildings, factories and new communities.

Da Zhuang Xu Jia village, 2013. At the time this shot was taken, a resident of one of these seaweed houses shared that he, along with others, would shortly move into new apartments (the four high-rise grey blocks featured in the image).

I have been studying and photographing seaweed houses since 2008. During this time, I have interviewed and worked with professors, scholars, photographers, journalists, residents, and builders of the seaweed homes to understand and document their building structures, basic history, customs, situations, and knowledge of seaweed. With my photography, I hope to leave an archive for future generations to appreciate the history, cultures and traditions of those who built and lived in seaweed houses.

Ma Shan, 2012.

Xu Kou village, 2009.

Xu Kou village, 2009. Inside the bedroom of a seaweed house.

Banner image: Ma Dao, 2008. Every winter, a great number of swans flock to the Ma Dao region, where the seaweed houses are located. All images courtesy of Yajing Liu.

|

Yajing Liu is a photographer working in the field of landscape photography and alternative hand-colouring processes. Her current research explores issues of cultural memory brought by rural landscapes and heritage under the urbanisation of China. Yajing’s photographs have been published in several magazines and screened in solo and group exhibitions and photography festivals worldwide. She is a PhD candidate at the School of Art, Design and Media at the Nanyang Technological University, and received her MA degree from the London College of Communication, UK. She can be reached at YLIU038@e.ntu.edu.sg |

Comments