By Peter Bingxuan Wang

Since arriving in Singapore in the June of 2019, I have been fascinated by the linguistic and cultural diversity of a country whose people of various ethnicities and cultural backgrounds live harmoniously together. I also learned that every local student studies not only English but also their mother-tongue language—Mandarin for the ethnic Chinese, Malay for the Malay community, and Tamil for Tamil Indians. The second-language policy in Singapore strikes me as unique, as it does not apply to a region like my hometown of Beijing, where the Mandarin-speaking Han people constitute the vast majority; nor in the US where I attend college. In large parts of China, where everyone’s mother tongue is Mandarin, speaking good English is considered a sign of educational distinction and usually leads to greater career opportunities. But studying English at more advanced levels is expensive, so not every student has access to this opportunity. Therefore, intrigued by the relationship between language proficiency and privilege, I was interested to examine the ethnicity-based second-language policy in Singapore. This led me to focus on the Special Assistance Plan (SAP) schools .

SAP schools are referred to as 特选学校 (texuan xuexiao) in Chinese

At the workplace where I was serving my internship, one of my Singaporean co-interns happened to be a SAP school alumna and two others had friends who attended SAP schools at primary and/or secondary levels. Through my conversations with them, and in reading the available literature, I got the impression that the typical SAP school student has access to an enhanced knowledge of the Chinese language and culture, excellent teachers in all other subjects and outstanding peers for company. I was also made aware of the fact that these schools have occasionally been called out for breeding “Chinese elitism” and contributing to racial divisions in Singapore. But how valid are the criticisms? What and who are at stake? In my limited time here, I attempted to take as deep a dive as possible in the topic. My aim was to gather all the information I could find about the SAP school system and to form my own views on the subject.

A Brief History

During the 1970s and 80s, English was perceived to be the language that guaranteed jobs and access to the global market, so increasing numbers of Singaporean parents sent their children to English-medium schools. This caused many vernacular schools—Chinese-, Malay- and Tamil-medium schools—to shut, eventually leading to all schools using English as the official medium of instruction in 1987.

Image via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Special Assistance Plan was implemented by the Singapore government in 1979 to preserve the ethos of the Chinese-medium schools and promote the learning of Chinese language and culture. Under this programme, nine Chinese-stream secondary schools were selected to serve as SAP schools, and geared towards producing effectively bilingual students in English and Mandarin.

Quick Facts

*In addition to language courses in Mandarin, elective courses in Chinese history and culture (such as tea appreciation, calligraphy, weiqi (go), Chinese drama and Confucian philosophy) are also offered at some SAP schools. *SAP schools require students to be in the top 30% of their PSLE cohort. *Many SAP schools offer exchange programmes with China. *School anthems and mottos are usually reflected and recited in Mandarin. *The architectural design and physical features of SAP schools usually carry Chinese influences, such as mini bamboo forests, red pillars and green tiles, and the statue of Confucius. *Besides the “SAP school” category, there are other types of schools, such as “Autonomous,” “Independent” and “Integrated Programme” schools. These categories aren’t always exclusive of one another: it is possible, for instance, for a SAP school to also offer the Integrated Programme.

SAP Primary SchoolsSAP Secondary Schools

- Ai Tong School

- Catholic High School (Primary)

- CHIJ St. Nicholas Girls’ School (Primary)

- Holy Innocents’ Primary School

- Hong Wen School

- Kong Hwa School

- Maha Bodhi School

- Maris Stella High School (Primary)

- Nan Hua Primary School

- Nanyang Primary School

- Pei Chun Public School

- Pei Hwa Presbyterian Primary School

- Poi Ching School

- Red Swastika School

- Tao Nan School

Source: Wikipedia and the respective school websites.

- Anglican High School

- Catholic High School

- CHIJ Saint Nicholas Girls’ School

- Chung Cheng High School (Main)

- Dunman High School

- Hwa Chong Institution

- Maris Stella High School

- Nan Chiau High School

- Nan Hua High School

- Nanyang Girls’ High School

- River Valley High School

Notably, SAP schools were introduced at a time when vernacular schools were on the verge of vanishing. As a result, SAP schools were tasked with the role of preserving the linguistic heritage and ethos of “the old Chinese schools”—“courtesy, respect for authority, discipline, awareness of one’s cultural roots and social responsibility", as outlined by former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in his book, My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore’s Bilingual Journey . The schools chosen to host the SAP programme were government-aided institutions founded by the Chinese community, and the selection was based on their well-established traditions, academic performance, facilities, staff and popularity with parents. They were also provided with the best teachers and received government assistance to improve their facilities. Malay- and Tamil-medium schools, however, were not revived by a SAP programme, because there were not enough students at the time to form a student group and compete with elite schools. By the mid-1980s almost all Malay- and Tamil-medium schools had completely disappeared.

Forty Years Later: Crème de la Crème?

What I find more troubling about SAP schools has less to do with their distinctly “Chinese” identity, but the fact that they appear to make up a substantial portion of Singapore’s top schools.

Image via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Image via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Ministry of Education (MOE) may have abolished its practice of ranking schools in 2012, but SAP schools continue to be considered the cream of the crop. Parents who still see some value in rankings now turn to websites that claim to aggregate examination scores and position schools in order of excellence. One of these is Salary.sg: in their “Best Primary Schools 2018” list, 10 out of their “Top 20” primary schools were SAP schools, while their “Top 4” positions were occupied by SAP schools. A secondary schools edition is also available: it showed that 8 out of all 11 SAP secondary schools were placed among the “Top 20”. These online rankings are not by any means endorsed by the MOE, and their data is only to be taken at face value. However, their findings corroborate the prevailing belief that SAP schools are synonymous with top schools—in these surveys, SAP schools take up 50 and 40 per cent of Singapore’s top 20 schools at primary and secondary levels, respectively. If this were true, wouldn’t it mean non-Chinese students have fewer top schools available to them?

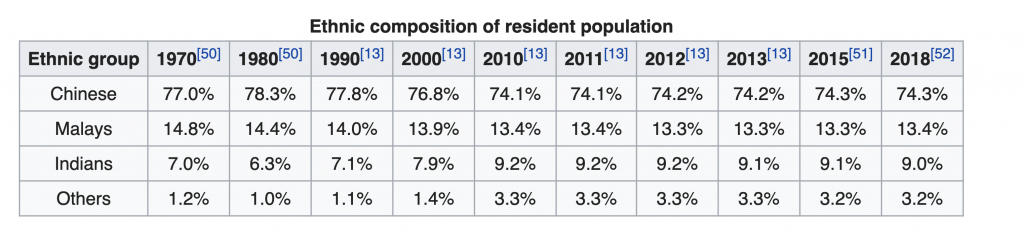

Demographics

Four decades since SAP schools were first established, Singapore’s overall population has burgeoned (from 2.38 million in 1979 to 5.64 million as of 2018), and the “Indian” and “Other Races” communities have seen a growth of 1–2 per cent. Yet today the SAP institutions still cater mainly to Mandarin-speakers and have racially homogenous cohorts. As long as this is the case, and if there are no updates to the national “mother tongue” educational policy, it remains unfeasible for non-Chinese students to apply to SAP schools.

Singapore’s resident population by ethnicity, 1970–2018 (Source: Wikipedia, via Department of Statistics)

Singapore’s resident population by ethnicity, 1970–2018 (Source: Wikipedia, via Department of Statistics)

However, some people are of the opinion that the existing non-SAP top schools are sufficient for the non-Chinese student population. This was certainly the impression I got from Zigi Cheong, a SAP school alumna and current student at Yale-NUS. Though she agreed with the notion that most top schools appeared to be SAP schools, she also supposed that things “evened out” by virtue of demographics:

“Given that the Chinese make up around 75% of the population and SAP schools only take up about a fraction of the top 50 or so schools, non-Chinese students still have many options. So maybe it’s not a reality they feel too strongly about.”

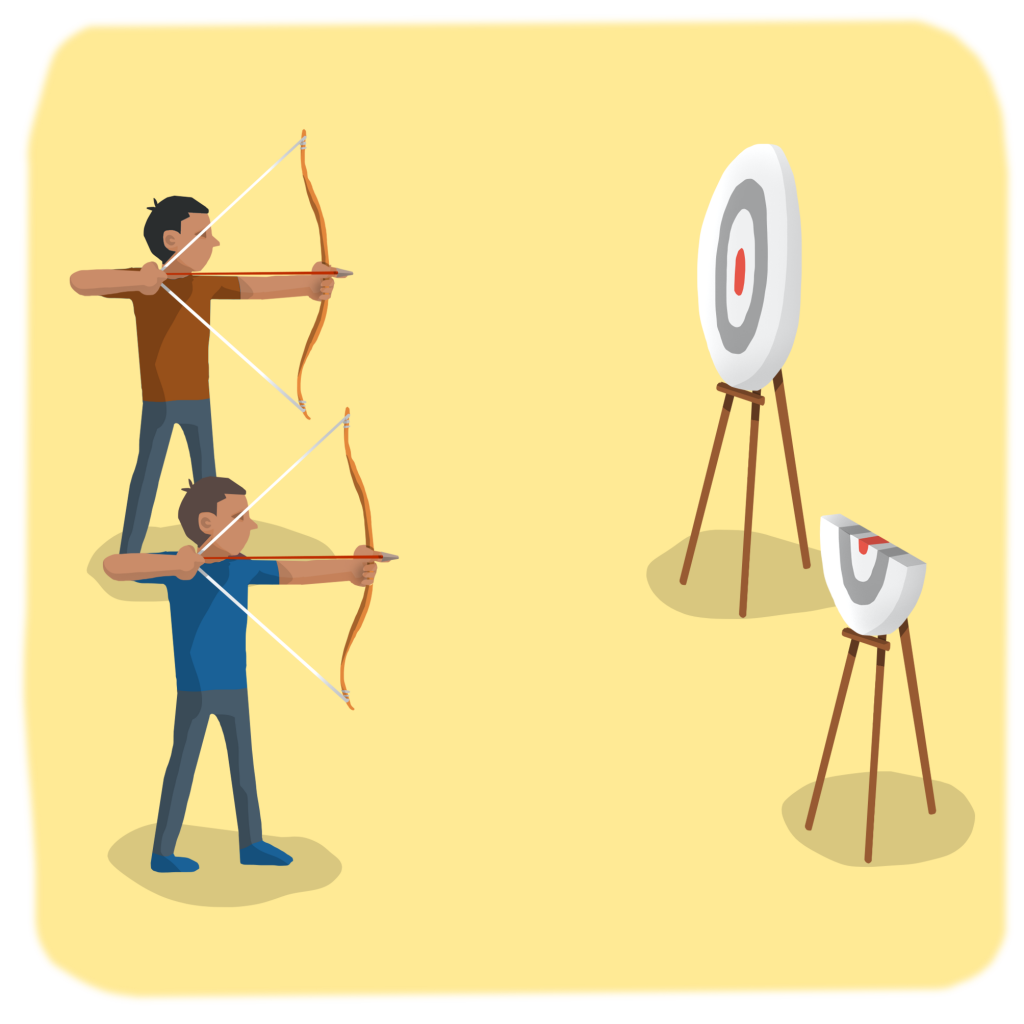

Yet this argument seems flawed to me. Let’s paint a visual representation: if all students were participating in an archery competition, the non-Chinese student’s target would be half the size of their opponent's. It’s simply an uneven playing field.

Illustration by Joseph Tey

Illustration by Joseph Tey

This Business with China

Another highly documented reason used to justify the establishment and preservation of SAP schools is this so-called “need” to nurture a core group of Mandarin-proficient Chinese Singaporeans who understand China on a cultural level, and can spearhead business exchanges with Singapore’s largest trading partner. As such, SAP schools have been receiving MOE funding to enhance the Chinese-oriented components of their curriculum. The Bicultural Studies Programme, for example, offers SAP school students the opportunity to go on immersion trips to Chinese cities to learn more about China’s culture, history and social reality. Hwa Chong Institution, notably, has satellite campuses in Beijing, Wuxi and Xi’an.

Image via Unsplash

Image via Unsplash

However, since the Bicultural Studies Programme is only offered by SAP schools, students outside these institutions are precluded from such opportunities. This leads me to wonder: if the perceived value behind such exchanges are increased business potential with China, why shouldn’t students of other ethnicities stand to benefit from such a programme? Come to think of it, have non-Chinese students and their parents been asked if these opportunities are of value to them?

The SAP Bubble

In 2017, The Straits Times published a story about minority students attending schools with a strong Chinese heritage. It featured Tinesh Indrarajah, an alumnus of Hwa Chong Junior College. HCJC is technically not a SAP school but one that draws the bulk of its students from two SAP secondary schools—Hwa Chong Institution and Nanyang Girls’ High School—and maintains a strong Chinese cultural heritage. Curious to know more about Tinesh’s experience of being a South Asian student at a Chinese-majority school, I reached out to him and he agreed to an interview. During our chat, he shared that he was the only non-Chinese member in a class of 26, but was glad that most of his schoolmates conversed in English. He described his years at HCJC to be generally enjoyable, but also found the ethnic homogeneity at SAP schools (and their extensions in JC) “troubling”—for many of his Hwa Chong friends, he was their first non-Chinese classmate.

Image via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Image via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The SAP schools themselves are seemingly aware of the lack of cultural diversity on campus and their students’ minimal contact with peers of different races. This may explain efforts to celebrate Racial Harmony Day and organise cross-cultural co-curricular activities, though these can hardly compare to the actual experience of attending school with classmates of other ethnicities and the daily interaction this provides. Chelsea Ong, who attended a SAP school and is presently an undergraduate at Yale-NUS, described the “bubble”-like environment of her secondary years. In hindsight, she wondered why nobody thought to question if they were being inclusive, and cited a particular incident:

“We’d have celebrations in school, where the emcee would speak in Chinese, even though the school had non-Chinese teaching staff who probably couldn’t understand a word. But nobody really noticed, because everyone just assumed any non-Chinese person knew Chinese.”

Wanting as well to get an educator’s take on the issue, I reached out to several SAP school personnel. Almost all turned me down, stating that they could not speak with authority on this subject. One teacher, however, agreed to an interview on the grounds on anonymity. Ms Tan (not her real name) said that she’s observed a “rise in Chinese elitism in recent years” at the educational institution where she works. Her remarks were candid:

“Many of the students and even teachers believe that the Chinese are the top contributors to Singapore and that the other races are just hangers-on. But if all top students went to SAP schools and they were all Chinese, wouldn’t it just feed the narrative that students of other ethnicities are ‘not good enough’?”

Looking Ahead: Room for Innovation?

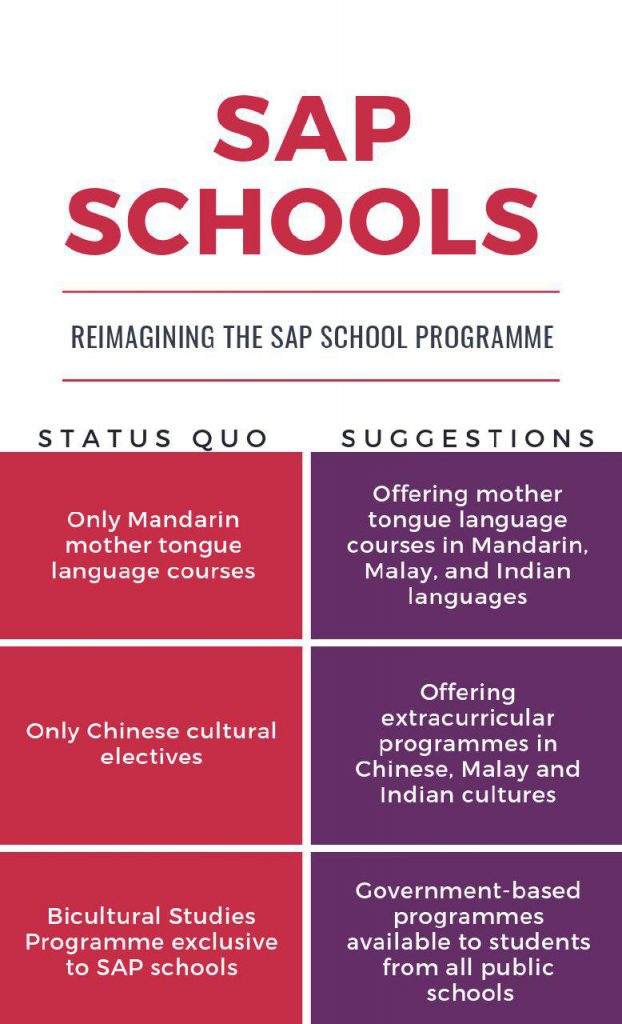

At the moment, resources exclusive to SAP schools are exclusive to Mandarin-speakers, so any plan for moving forward should examine ways to make them more widely available. The following are some suggestions to consider. i) SAP schools’ Chinese curriculum could be adapted for the existing language elective programme of other schools and the various MOE-established language centres. ii) Supplementary classes in Chinese culture and history could additionally be offered as extracurricular content for interested students, along with similar courses in Malay and Indian cultures. iii) Cultural exchange trips can be extended to more countries (River Valley High School already has multiple countries included in their Internationalisation Programme), and this need no longer be exclusive to a SAP school, but open to schools nationwide, regardless of student ethnicity. iv) SAP schools, on their part, should consider expanding their number of mother-tongue-language offerings. In so doing, they can welcome a more diverse cohort of students and effectively end any criticism relating to their language-based exclusivity.

Suggested improvements to the SAP school framework. (Source: content by the author; special thanks to Linda Wang for the infographic design)

In terms of an existing model, it might be helpful to look to that of Singapore’s mission schools, which remain inclusive while maintaining their core identities. Faith in Christianity, for one thing, is not a requirement for admission at these schools, and non-Christian students and faculty need not partake in religious ceremonies. At St. Joseph’s Institution, a Catholic all-boys mission school, prayers and other religious ceremonies are welcomed, but not required of non-believers, who can instead “reflect in their own way or maintain a respectful silence while others are participating in the practices/beliefs.” In a similar vein, could SAP schools not reframe their strong Chinese identities as a sort of ethos instead of making it a criterion?

As a foreign student who has only spent two months here, I am not by any means claiming to have an in-depth understanding of Singapore society and its education system. Based on my research, interviews, and inferring from the sheer numbers of high-calibre graduates that SAP schools have produced, I see only merit in extending its attributes to more schools and students.

The purpose of this commentary is not to posit that there may be a one-size-fits-all way forward. Rather, I hope to enrich the conversation on SAP schools, and to urge more non-Chinese parties to join the discussion. Such as Tinesh. Nearing the end of our interview, he mentioned a chat he’d had with his 11-year-old niece some years ago. When he asked if she’d like to study at Hwa Chong Junior College in the future, her answer was no, simply because “it’s a Chinese school”. Hearing this saddened Tinesh, though he could understand where the sentiment was coming from. “Even someone that young already believes certain schools are not viable options for them,” he said. I then asked Tinesh what sort of change he hoped to see. His answer was simple and unsurprising: that all schools become “viable” schools for all peoples, regardless of their mother-tongue language.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Chen Jinwen, Han-Peng Ho, and Eunice Rachel Low for their advice and guidance in the writing of this article. Special thanks also go to Christy Davis, Dalvin Sidhu and Halimatus Saadiah who read an earlier draft and offered helpful comments.

Banner image designed by Valencia Toh.

|

Peter Bingxuan Wang was a 2019 Summer Associate (Editorial) at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation. Originally from Beijing, Peter is currently a rising third-year student at Columbia University in New York, where he majors in Philosophy. Interested in the intersection between journalism and social activism, he writes for his school newspaper and is involved with an educational non-profit. In his free time, Peter enjoys travelling, watching movies and reading any book that falls into his hands. He can be reached at bw2550@columbia.edu |

Comments