By Lim Kien Chern

In March 2021, National University Student (NUS) Dana Teoh wrote an opinion piece titled “This is why I don’t want to be woke. Don’t cancel me for it”. Unsurprisingly, the piece became the subject of heated online debate that eventually led NUS’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences to speak out in her defence. In summary, Dana’s piece is about the dangers of Cancel Culture; that the fear of being judged or “getting cancelled” might lead to blind conformity.. While Dana’s concerns about the need to appear “woke” at the expense of true understanding and freedom of speech are valid, I feel that her piece focused too much on the outcomes of Cancel Culture without addressing the contexts that it operates within. By reconciling these two concepts, I hope to contribute to a clearer portrayal of Cancel Culture as a subset of popular movements that respond to social injustices, and how it can be utilised for good.

Cancel Culture’s roots can be traced back to Civil Rights era boycotts, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycotts in mid-1950s Alabama. In the face of racial segregation on the Montgomery Bus Line, the African American population, which constituted 75% of the bus service’s riders, mobilised boycotts. After one year, discussions held by the organisers of the boycotts and legal proceedings eventually resulted in racial segregation on buses being ruled as unconstitutional; proving to be a watershed moment in the Civil Rights Movement. In essence, Cancel Culture is similar: it is the withdrawal of support for a public figure or organisation with which one disagrees. When practised on a scale large enough, this can result in substantial consequences for those targeted. Cancel Culture has facilitated a number of social movements in America, such as the #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo campaigns. In Singapore, it has appeared in various causes such as LGBT rights and gender equality, which will be addressed in this commentary.

Credit: Mothership

Credit: Mothership

However, directly translating the concept of the boycott to the realm of social media can prove to be problematic, and Cancel Culture does indeed have major drawbacks. In her article, Dana cites the example of transgender individuals by stating that: “in a room full of woke people, I would probably just sit quietly, smile, and nod if someone said, ‘Children should have access to puberty blockers, no questions asked!’”. This illustrates how a prevalent Cancel Culture that relentlessly cancels individuals for ignorance can lead to self-censorship, something which is enabled by participatory acts as simple as sharing a post or tweeting a comment. This stifling of discourse is harmful to all parties as no one walks away with a better understanding of the issue at hand.

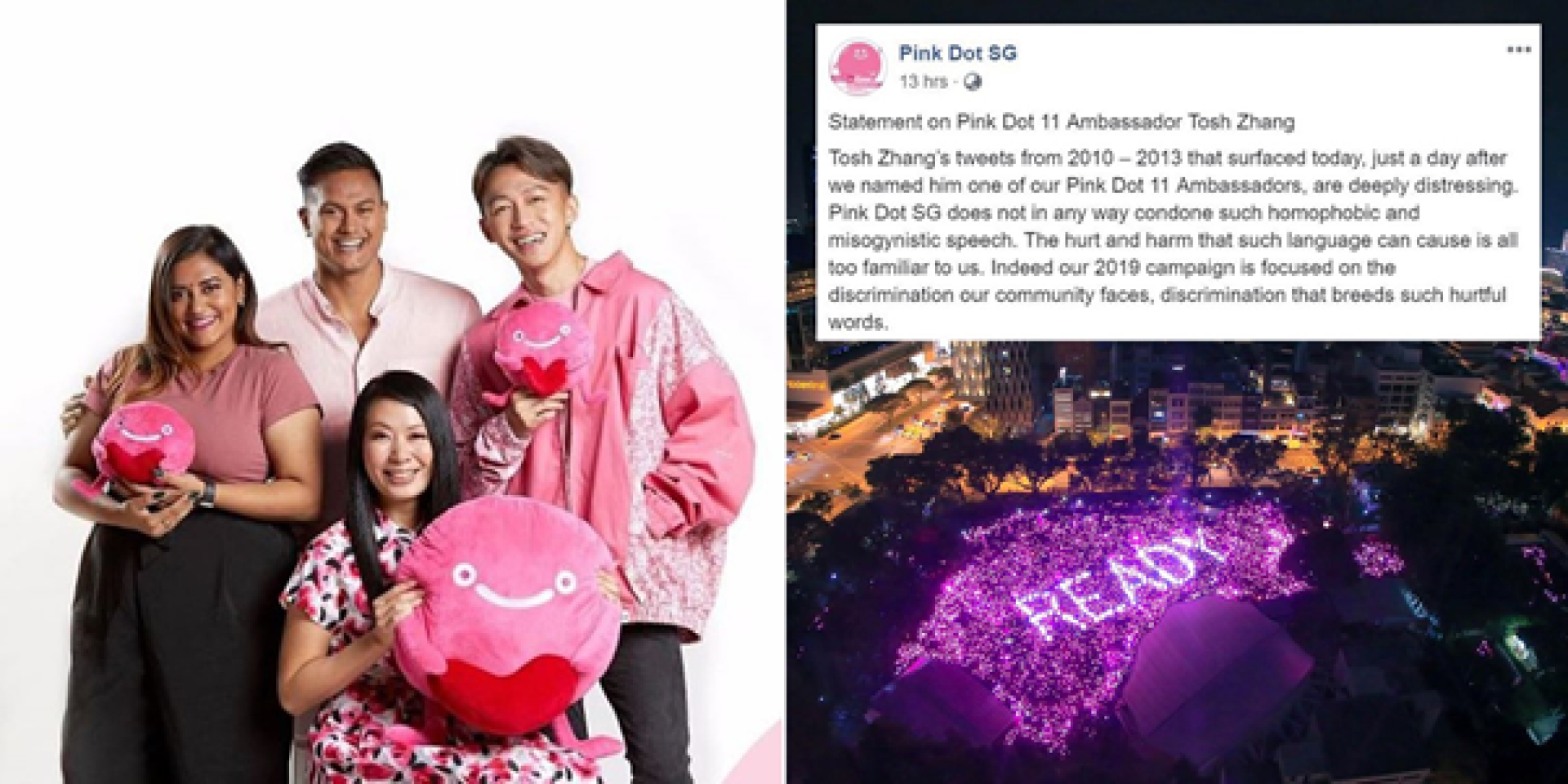

Cancel Culture also often comes across as public shaming — where individuals are ostracised or dismissed for their opinions. In addition to generating a climate of self-censorship, this process of public shaming can punish individuals for transgressions long past. In 2019, Singaporean celebrity Tosh Zhang was selected as the ambassador for Pink Dot’s pride parade. When screenshots of homophobic tweets posted by him around 6 years prior surfaced, he was quick to apologise. Despite this, he felt the need to step down in the face of the online outrage that followed.

Yet, while it might seem harsh that Tosh received such harsh criticism for comments made from a time so long ago, the backlash should be considered within the wider context of the LGBT community in conservative Singapore. Homosexuals represent a minority that feels the effects of social stigma and legislation (such as Section 377A of the Penal Code and the criminalisation of gay marriage) in everyday life. The social media furore and reporting by newspapers generated by the incident demonstrate how Cancel Culture allowed a minority group (and their supporters) to reach the mainstream media and send a message in support of the LGBT community.

Credit: Pink Dot SG

Credit: Pink Dot SG

The mainstream media represents a public sphere that is traditionally dominated by social elites, ranging from the government to influential businesses. Social media, on the other hand, represents a more dynamic and accessible (albeit less-than-formal) sphere of the public over which minorities have greater influence—allowing the potency of Cancel Culture to bridge the divide between the two.

In her aforementioned example, Dana seems to imply that it would be easy to find a setting where the majority of individuals wish to protect the rights of Singapore’s trans community. Seeing that trans individuals still largely lack the support of our institutions, however, I think that one would be hard-pressed to find a room full of such people. This illuminates the power dynamics at play and hence why the potency of Cancel Culture is a powerful asset for minorities to challenge the status quo with.

One example of when the power of social media was successfully harnessed and gave minorities a platform to right the wrongs done to them was a case in 2019 when NUS undergraduate Monica Baey called out her perpetrator on social media for an act of voyeurism committed against her. In response, many members of the public called for Nicholas Lim to receive harsher punishments, drawing attention to inadequacies in NUS’s framework for dealing with sexual assault. Following this, NUS initiated a Town Hall dialogue and established a Victims Care Unit for sexual assault cases.

Having said this, Cancel Culture is like a double-edged sword that should be approached with caution, openness, and empathy. The nature of social media provides immediacy and a sense of detachment that can make or break a situation.

Unlike the Montgomery Boycotts, where large numbers of people needed to mobilise themselves physically,social media does not suffer from the same constraints. The accessibility of these platforms mean that nearly anyone can contribute to an online conversation. So while it may enable us to raise public awareness on social justice on a scale larger than ever before it may also be difficult to organise formal dialogues with institutions-as was the outcome of the Montgomery Boycotts. In the polarising echo chambers of social media, pinpointing the precise source of injustice might prove difficult; let alone organising the masses into a cohesive unit. This increases the likelihood that a climate of self-censorship that is not channelled into any meaningful systemic change develops, as Dana alluded to.

Credit: Straits Times

Credit: Straits Times

Rather than jump blindly into the next online witch-hunt, perhaps we should also take a step back and ask ourselves how much we believe in personal growth? At what point do we accept an individual’s apology out of a belief that everyone is capable of change and improvement? It is vital that we learn to strike a balance between justice for all and being humane.

Cancel Culture can cause serious damage, but can also generate awareness for good. I believe that an understanding of one’s responsibility to steer the conversation in a direction that can facilitate lasting change is vital in every form of participation, whether in the form of commenting on a Facebook post or engaging in dialogues with an institution. Social media has become an integral part of our lives,, and sharing this understanding has become all the more important if we are to mitigate the ills of Cancel Culture and allow it to serve its original purpose as a movement for social justice.

Unless otherwise stated, all photos via Rawpixel.

References

- Dana’s piece on Today

- Defining and targeting Cancel Culture

- Different outcomes of Cancel Culture when focused on individuals versus institutions

- Effect of Monica Baey incident on institutions and social movements

- Nicholas Lim bullied

- Lack of institutional support for minorities such as transgender communities

- Recent racially-charged cases of assault or abuse in Singapore

- https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/pm-lee-and-some-ministers-speak-out-against-alleged-racist-attack-woman-choa-chu-kang

- https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/ngee-ann-poly-suspends-teaching-staff-member-seen-racist-video-confronting-inter-ethnic

- https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/ngee-ann-poly-suspends-teaching-staff-member-seen-racist-video-confronting-inter-ethnic

- Tosh Zhang and Pink Dot

- Montgomery Bus Riots

- NUS FASS and Prof Bertha Henson statements

- MeToo movement

- BlackLivesMatter

- Bouvier, G., & Machin, D. (2021). What gets lost in Twitter “cancel culture” hashtags? Calling out racists reveals some limitations of social justice campaigns. Discourse & Society, 32(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926520977215

- D. Clark, M. (2020). DRAG THEM: A brief etymology of so-called “cancel culture.” Communication and the Public, 5(3-4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047320961562

|

Kien Chern is a Year 2 Politics, Law and Economics undergraduate at Singapore Management University. He enjoys rewatching shows on Netflix in his free time as well as a game or four of DOTA. Look out for his pieces on Social Space as he tries to understand the world and more often than not ends up a tad bit more confused! |

Comments