By Andrew Koh

“We want a nice colour and it must look modern.” That was the feedback some villagers gave during a design-thinking exercise regarding sanitation facilities as part of my previous work in the international development sector. Although this took place several years ago, I remember the experience vividly because it struck me that most people—village-dwellers or Singaporeans alike—have similar aspirations for a better quality of living. It is plain to see the social impact of technological advancement on needy communities—consider how a mechanical pump allows villagers to draw water more efficiently, or the range of benefits brought about by rural electrification—but beyond the systems and contraptions themselves, how can we leverage technology for social innovation?

Context Matters

Social innovation, defined as “the process of developing and deploying effective solutions to challenging and often systemic social and environmental issues in support of social progress”, focuses on ideas and solutions that create social value. Technology alone is unlikely to catalyse impactful solutions—rather, it is in its appropriate application that a real difference can be made.

Similar to the ground-up participatory spirit in design-thinking, real needs must first be identified before a solution can be designed and implemented. This involves understanding the communities (the people, their cultures and skill sets) we hope to impact, as well as examining their concerns within the context of their existing systems and infrastructures.

If you were to recall a teacher in school who left a lasting impression on you, which aspect(s) of that experience are embedded in your memory? Would it be specifics of the content taught, or the personality of the teacher? More likely than not, what’s caught is often more important than what’s taught. To gain the necessary insights that ultimately translate into innovative responses, we first need greater exposure to the communities in question.

This means more ground experiences with the people, interacting with them as well as witnessing first-hand the specific issues they face. Only then can we gain heightened awareness of their needs and come up with informed design solutions.

Businesses Play a Big Role

Multinational corporations are well placed to lead social change, given their wide scale of operations and extensive geographical network. With regional offices located in close proximity to underserved communities, their reach covers areas that are exposed to poverty and lack basic infrastructure, granting the organisations both the on-site experience of working and interacting with the local community, as well as the opportunity to use their brand platform to spearhead targeted social programmes.

For instance, Olam International, a soft commodities processor and trader, has implemented an application to empower subsistence farmers with training, enhanced farm management and banking services to increase their quality of life. In another example, Coca-Cola’s 5by20 initiative educates and provides livelihood opportunities to female owners of small-scale neighbourhood markets and grocery stores, and by extension, empowers the low-income communities which they belong to. However, multinational corporations are not the only ones making strides with their social impact programmes. In Singapore, several social enterprises and start-ups, such as SMU-TCS iCity Lab, Homage and WateROAM, have successfully harnessed technology to bridge the gaps between needs and solutions.

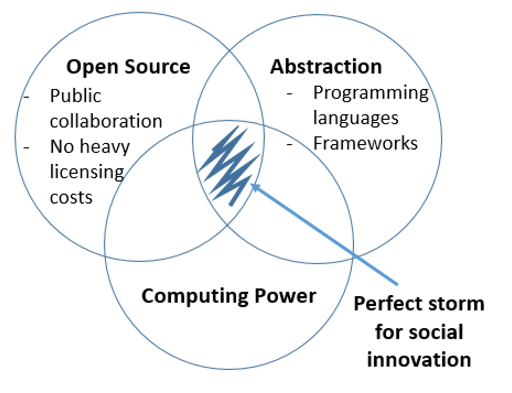

Creating the Perfect Storm

So what are some ways in which technology can become a wave of disruption? Beyond buzzwords like “Artificial Intelligence”, “Machine Learning” or “Big Data”, we should examine some characteristics of the tech wave and which aspects make a perfect storm for social innovation.

Open Source

Open source refers to technology developed through a public collaboration and made freely available. This reduces the need for heavy licensing costs, making it possible for marginalised communities with low purchasing power to utilise technology previously out of reach to them. Business models with less dependence on expensive technology are more sustainable and hence more viable for serving these communities.

Abstraction

In recent years, higher-level programming languages have been developed to make programming a less laborious process. For instance, machine learning models can be trained and employed by using a few lines of code in open-source languages such as R or Python instead of hundreds of lines if more traditional languages such as C++ were used. The use of commodity hardware to store, manage and analyse large volumes of data is another form of abstraction. In the past, specialised hardware and programming complexity were needed for handling huge volumes of data. This was until 2006, when a framework called Hadoop was developed to handle such data using commodity hardware, which lowers costs and complexity.

Computing Power

When you hear of deep learning today, it is based on neural networks that have existed since the 1950s. However, the way it has penetrated our daily lives (think of Amazon Echo or face recognition in Google Photos) is due to computing power leaps that allow its capabilities to be delivered in near real time for widespread usage. Simply put, the barriers to the adoption of technology have been lowered. Platforms and services today make these advanced capabilities available to the wider audience, not only to large corporations with deep pockets. For instance, NPO Trampolene has built an app (the SmartBFA) that leverages crowdsourced data to provide obstacle- and barrier-free routes for wheelchair users in Singapore.

Shared Social Responsibility

“With great power comes great responsibility.” So said Uncle Ben to Spider-Man’s Peter Parker, although this principle has also been attributed to Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt. By and large, people look to the Internet for information and to share it with others. However, the world wide web has also become a space where one can be susceptible to cyber bullying, phishing scams, “fake news”, and data and privacy infringements. The recent data breach incident involving Cambridge Analytica—in which about 50 million Facebook users’ information was used for political purposes—is an example of how technology can be misused.

Therefore, for technology to be a responsible disruptor of change, there first needs to be oversight and safeguards in place to ensure cyber safety to tech users the world over, especially those from vulnerable communities.

As the barriers to the adoption of advanced technology lower, we are seeing a rise in the application of “social tech”, or technology for social impact. Universities and social enterprises offer good training grounds for an emerging generation of tech-proficient changemakers seeking a higher purpose in their professional as well as personal endeavours. However, while technology itself is known for its speed and efficiency, its application for positive social outcomes will not yield overnight results. The process requires a team of multi-disciplinary thought leaders and passionate changemakers who understand both the context and culture of the underserved communities, and who can explore relevant ways in which technology can be the essential bridge.

|

Dr Andrew Koh is a Practicum Manager for the Masters of IT in Business programme (with specialisations in Financial Technology, Analytics and Artificial Intelligence) at the Singapore Management University. Prior to joining SMU, he was a Microsoft Data & Analytics Partner Seller, a select group to augment Microsoft's technology specialist team. Earlier in his career, he spent a few years in the international development sector, where he worked with social enterprises to empower youth and marginalised communities in Cambodia. Happily married and a father to two young boys, Andrew loves being in nature with his family. He can be reached at andrewkoh@smu.edu.sg |

Comments