By Shee Siewing

From TV programmes, to newspapers, books and magazines, traditional media’s depictions of youth have tended to dwell on either sides of two extremes: hapless victims or violent perpetrators. In Stanley Cohen’s 1972 work, Folk Devils and Moral Panics,5 he describes how these dismissive media portrayals of youth have fixed the public’s general perceptions of them in a particular way that has had lasting and far-reaching effects. In recent years, a number of youth victimisation cases have also dominated Singapore’s news, involving cases of “none the-wiser” teens being duped by cyber scams, and suffering sexual or financial exploitation as a result.6 Attempting to explain this trend, social workers attributed youth’s “often naïve, trusting” nature to their “especially vulnerable” position in society.7 Ironically, when not suggesting more should be done for these helpless youngsters, there are just as many news stories and national statistics on youth crime, delinquency and drug abuse, which present a darker side to this group.8

As worrying as the phenomenon” of youth violence and arrests may seem at first glance, the numbers, when presented in relative terms as a proportion of all youth in Singapore, paints a more optimistic picture. In 2016, only 0.5 per cent of all youth in Singapore were arrested for youth crime,9 which means that the overwhelming majority (99.5 per cent) were engaged in other, presumably nonlaw-breaking, activities. Singaporean parents may also be glad to know that the vast majority of the nation’s youth are not “troubled”—in fact, with 74 per cent regarding “maintaining family ties” as a very important life goal,10 they are quite “homey”!

|

What first comes to mind when someone mentions “young people” or “youth”, and how much of your impression is determined by the last news article you read? If you are wont to use “reckless”, “troublemakers”, “self-absorbed”, “obsessed with social media” or “lacking in self-control” in the same sentence as “youth”, this could be the doing of the traditional mass media, whose reportage on this demographic consistently overstates an involvement in risky behaviours. In his 1998 seminal work, Moral Panics, social scientist Kenneth Thompson claimed, “No age group is more associated with risk in the public imagination than that of youth.”1 Now, decades after this claim was made, it appears that little has changed. A simple Google search on “Youth in Singapore” yields reports pertaining to teen violence and misadventures on dating sites;2 in the United States, youth make the most headlines for school shootings;3 and in 2008 alone, more than half of the UK’s national and regional newspapers’ coverage of teenagers had to do with crime.4 |

What's Age Got to Do With It?

While society may have been quick to establish a direct link between age and delinquency, it is also worthwhile to examine the wider issues behind youth’s particular “susceptibility” to “acting out”. This point is supported by Mr Ho Peng Kee, formerly the Senior Minister of State for Law and Home Affairs and Chairman of the InterMinistry Committee on Youth Crime, who emphasised that “no single factor explains why youths turn to crime”.14 One view argues that, among affected children, parental divorce causes family instability and triggers “psychological problems such as separation anxiety, grief and lower self-esteem,”15 thus leading them to seek solace in “risky behaviours”.

Yet, on the other hand, statistics reveal that troubled youth do not all originate from single-parent families:16 a study examining the family structures of young offenders arrested in Singapore between 2013 and 2014 showed that only 53 per cent17 came from families with separated or divorced parents. This is substantiated by Gus Martin’s point that it is the discord in a household, rather than family make-up, that can prove “much more disruptive” to a child.18 Besides family instability, the pressures of school and grades have also been identified as a major source of unhappiness for Singaporean youth aged between 15 and 18.19 This corresponds with the findings in a 2004 national report on marriage and parenthood,20 which highlighted how high parental expectations towards children’s academic performance contributed significantly to the latter’s stress levels.

In light of the above, I suggest that it is youth’s sense of disengagement—rather than age—that predisposes them to “risky behaviours” (online and off), but this is a separate topic that deserves closer examination, and the scope of it will not be covered in this article.

Minority Report

According to Philip Graham’s classifications of individuals, the youth population of most developed nations can be parked under the “problematic minority” group21—this applies to Singapore as well, whose 3,000-something “troubled” youth constitute a mere 0.5 per cent of its whole youth demographic.

Considering its “minority” standing, the disproportionate amount of attention that traditional media pays to it is puzzling. It is plain to see that other groups (the elderly, children or adults) are not as closely associated with risk, crime and violence, and this leads one to wonder if a particularly ageist attitude against youth might be behind this obvious media slant. First coined by Robert Neil Butler in 1969 to describe discrimination against seniors,22 the term “ageism” has since expanded to encompass general age-related bias, stereotyping and unfair practices against individuals based solely on their age.

Similarly, the traditional media’s tendency to portray young people as synonymous with traits such as powerlessness and vulnerability, as well as lacking in knowledge, experience and the capacity to resist temptation, is suggestive of an “ageist” stance. The media’s negative typecasting of young people influences not only public perception, but has an impact on youth’s self-image as well.

Research shows that such age-based stereotypes lead some youngsters to believe they are of lower status, have fewer rights, and cause them to feel less motivated to speak out in general.23 In many countries, youth are seldom given the opportunity to contribute to decisions about public policies (e.g. national budget and urban planning), although Boston has proven a positive exception.

|

Boston: Doing Right by Youth

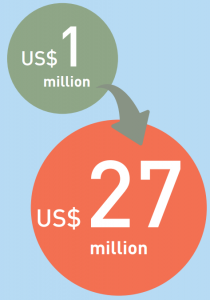

In Boston, Massachusetts, not only are its residents invited to participate in the city’s budget planning, those aged 12 to 25 in particular are targeted by the Mayor to come up with budgeting projects. Known as “Youth Lead the Change”, it is America’s first youth-driven city budgeting programme that works with youth to understand their needs, in order to ultimately create an inclusive city. Started in 2009 with US$1 million by the Mayor and his Youth Council, participatory budgeting for youth in Boston has presently expanded to US$27 million. Under this programme, high school juniors and seniors serve as volunteer representatives of every neighbourhood in the city. Forums are held regularly for young people to contribute ideas and solutions directly to the Mayor and other city officials, after which these are narrowed down to four initiatives that focus on improving Boston’s safety, environment and health, community and culture, and education. Following that, city residents vote for the top proposals, which go on to receive funding. Some of 2016’s winning project ideas by Bostonian youth include: playground renovations, art walls, park security cameras and new sidewalks. Throughout this year-long experience, not only do Boston’s youth become more informed about the inner workings of government, they gain the soft skills required to make thoughtful decisions within a limited time and budget. With them feeling like they have a stake in the planning of their living space, young Bostonians are all the more empowered to create positive impacts on their city’s design and liveability. |

Brand New Youth

While an image overhaul of youth is long overdue in traditional media, one need not hold his breath. With the emerging generation of millennials eschewing printed newspapers and magazines and turning instead to online news sites, blogs and social media for information and entertainment, the Internet and new media are giving traditional media a run for its money—as well as providing youth an alternative platform to be seen and heard. And with that, a different picture of youth is emerging.

Founder of Microsoft, Bill Gates, was a teenager when he discovered his forte in programming and wrote his first tic-tac-toe computer programme. That was several decades ago, when such remarkable cases were few and far between. However, today’s youth-led entrepreneurship scene is thriving by leaps and bounds: unlike before, when founding a start-up straight after graduation seemed like a foolishly risky endeavour, it is today viewed as something commendable—even viable. To meet young people’s growing interest in entrepreneurship as a career, more specialised courses are being taught by business schools and educational institutions.24

Today, armed with suitable knowledge and by being at the right place (read: online platform) at the right time, youth can meaningfully showcase their talents to an intended audience. As a case in point, after the Fiverr page (an online marketplace for digital services) of 15-year-old Singaporean student Hrithie Menon caught the attention of a Donald Trump staffer, Menon scored a gig to make a Prezi slideshow video for Trump’s campaign effort at college campuses.25 This Prezi went on to reach millions of students across US universities and high schools, and Menon’s public profile has since enjoyed a considerable boost: she is presently listed as a “Top Choice Level 1 Seller” on Fiverr.

Alongside IT-savviness and a keen entrepreneurial spirit, there is yet another positive trait often attributed to today’s youth: their social consciousness and desire to contribute towards positive social change.26 A 2016 survey showed that young people are increasingly eschewing luxury holidays for immersion-type trips in emerging countries like Myanmar to experience the cultures and living conditions of local communities; and many develop empathy in the process.27 In David Pong’s travels to Phnom Penh and Bintan, the 26-year-old Singaporean was shocked to witness the stunted growth of the local children as a result of improper nutrition and lack of clean drinking water. Recognising that “water affects everything in life”, he and his university mates set out to address water insecurity in such places by developing affordable and portable water filtration devices to improve the people's accessibility to clean water.28

Back home, it appears that the younger generation is just as acutely aware of prevailing social issues. Desiree Yang, a 23-year-old Singapore Management University undergraduate, became aware of low-income families’ inaccessibility to fresh food and dry rations during her internship at Beyond Social Services. Feeling for their plight, she and her father Mr Roland Yeo, 55, set up Singapore’s first social supermarket. Named Saltsteps,29 it sells goods and groceries rejected by regular supermarkets (for reasons such as mislabelling and torn labels) at significantly more affordable prices to low-income families, while reducing food wastage at the same time. Examples like these, set against the rapid rise of youth-led social enterprises around the world,30 suggest that youth may indeed have found a way to satisfy their dual passions for entrepreneurship and social change.

While it is not the intention of this article to downplay the severity of youth-related crime, I hope to have encouraged readers to put aside preconceived notions about young people (vis-à-vis traditional media) and to make up their own minds about them based on youth’s continuous strides towards meaningful change in an increasingly globalised and interconnected world.

|

Youth: Doing the Math The United Nations Organization for Education, Science and Culture refers to youth as young people of both sexes between the ages of 15 and 24, although UNESCO accepts the 15–35 age bracket as defined by the African Youth Charter.32 This category of young people also dovetails with the group known as “millennials” or “Generation Y” (those born between 1980 and 2000). In Singapore, the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth defines youth as persons aged between 15 and 35 years,33 while the Singapore Police Force places them between the ages of 7 and 19. Its definition is also culturally specific: certain individuals considered to be “youth” in one country or agency may be legally recognised as adults or children in another. Gen X,Y,Z Other than age brackets, the letters X, Y and Z are also used to differentiate youth according to different time periods (or “generations”). Demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe believe that each generation—owing to their shared experiences of major events—as common characteristics that give it a specific character. Gen X (b. 1960s-early 1980s) The culture and upbringing of Gen X’ers were shaped by global political events such as the Vietnam War, global sexual revolution of the 1960s–80s, fall of the Berlin Wall, end of the Cold War, and the Thatcher-era government. Compared to the previous baby-boomer generation, Gen X is more open to diversity and embracing of differences in religion, sexual orientation, class, race and ethnicity. Gen X’ers are also known as the “latchkey generation” (growing up with a lack of adult supervision due to having two working parents). Some famous Gen X’ers include Barack Obama, Victoria Beckham, Ben Stiller, Robert Downey Jr., Robbie Williams and Gordon Ramsay. Gen Y a.k.a. Millennials (b. 1980s–2000) Gen Y’ers are largely impacted by the technological revolution occurring since their childhood and teenage years. Numbering around 80 million,34 they are the largest age-specific demographic in American history. Due to the rapid globalisation of this period, Gen Y’ers are more exposed to Western culture than their predecessors. They are unfortunately associated with traits such as self-centredness, a sense of entitlement and narcissism.35 Some famous Gen Y’ers include Britney Spears, Mark Zuckerberg, Taylor Swift, Emma Watson, Justin Timberlake and Beyoncé. Gen Z (b. mid-1990s–present) There is the least information available about this group because Gen Z’ers are still in their teenage years at this present time. Also known as the iGeneration (in reference to their IT savviness and ownership of iPhones), they have been exposed to an unprecedented amount of technology since birth—and are understandably adept in the latest digital trends and use of social media. Gen Z’ers are further known for their resourcefulness on the Internet: they self-educate with YouTube tutorials and seek inspiration from sites like Pinterest. Some famous Gen Z’ers include Malia Obama, Willow Smith, Maisie Williams, Zendaya and Maddox Jolie-Pitt. |

Going forward, I hope both traditional and new media will cultivate a more inclusive environment for youth to express their ideas and opinions, especially in such areas as public policy. In Singapore, it is heartening to see the government placing a new emphasis on listening to young people’s feedback—as evidenced by the rising number of youth-centred dialogues and conversations in recent years31—and to witness the growth of youth-led start-ups that have been incubated through initiatives such as the National University of Singapore’s Overseas Colleges and SMU's Ashoka Changemaker Campus. No longer passive subjects of the traditional press, but active authors of the new media, today’s youth will soon be known for much more than what their historically negative stereotypes stood for.

Notes

1 Kenneth Thompson, Moral Panics (London: Routledge, 1998).

2 Lianne Chia, “Flirting with Danger: Singapore Teenagers on Tinder”, Channel News Asia, 7 June 2016 at http:// www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/flirting-withdanger/2849260.html

3 Deborah Dunham, “Here’s What the Media Is Doing to Teenagers Today”, Huffington Post, 30 August 2014, at http://www. huffingtonpost.com/deborah-s-dunham/heres-what-the-media-isd_b_5541462.html

4 Richard Garner, “‘Hoodies, Louts, Scum’: How Media Demonises Teenagers”, Independent, 13 March 2009, at http://www. independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/hoodies-louts-scum-howmedia-demonises-teenagers-1643964.html

5 Stanley Cohen, Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1972).

6 Janice Tai, “More Teens Falling Prey To Cyber-Scams”, The Straits Times, 12 June 2013, at http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/moreteens-falling-prey-to-cyber-scams; The New Paper, “Sexual Abuse Victims in Singapore: Young, Vulnerable, and Online”, AsiaOne.com, 2 May 2016, at http://news.asiaone.com/news/crime/sexual-abusevictims-singapore-young-vulnerable-and-online; Krystal Chia, “Teen Falls Prey to Online Scam; Ends Up with $1,363 Bill”, The New Paper, 19 May 2016, at http://news.asiaone.com/news/singapore/teen-fallsprey-online-scam-ends-1363-bill

7 Tai, “More Teens Falling Prey To Cyber-Scams”.

8 Hariz Baharudin, “More Young People in Singapore Turning to Violence”, The New Paper, 6 March 2016. There was an increase of 39 youth arrests for rioting in 2014, up from 283 in 2013. Home Team, “Home Team Annual Statistics: Overall Crime in Singapore Up by 7.4% in 2014”, Home Team News, 29 January 2015, at https://www.hometeam.sg/article.aspx?news_sid=20150129y0PtETqhf1G0

9 The number of individuals aged between 5 to 19 years stands at 648,780. Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, Population Trends 2016 (Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, 2016), at http://www.singstat.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/publications/publications_and_papers/population_and_population_structure/population2016.pdf

10 National Youth Council, National Youth Survey 2013 (Singapore: National Youth Council, 2013), at https://www.nyc.gov.sg/initiatives/resources/nys

11 Statistics is generated from data.gov.sg by classifying the total number of persons arrested in Singapore by age groups. See https://data.gov.sg/dataset/total-persons-locals-and-foreignersarrested?resource_id=77e140cc-406f-4a93-b05d-7e2fd7dd712e

12 Masami Ito, “Shifting the Scales of Juvenile Justice”, The Japan Times, 23 May 2015, at http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/05/23/national/social-issues/shifting-scales-juvenile-justice/#.WH8OL2R94zU

13 Hong Kong Police Force, “Crime Statistics in Detail”, last revised January 2017, Police.Gov.Hk, at http://www.police.gov.hk/ppp_en/09_statistics/csd.html. The total number of people aged 10 to 19 stands at 659,900 in 2014; see Census and Statistics Department, “Table 002: Population by Age Group and Sex”, last revised December 2016, Censtatd.Gov.Hk, at http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp150. jsp?tableID=002&ID=0&productType=8 14

14 Inter-Ministry Committee on Youth Crime, The Right Side InterMinistry Committee on Youth Crime Commemorating: A Decade of Partnership to Rebuild Young Lives (Singapore: National Youth Council, 2006)

15 Sundaresh Menon, “Keynote Address: Harnessing the Law to Benefit Our Youth”, at the Conference on At-Risk Youth 2015.

16 Terry-Ann L. Craigie, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn and Jane Waldfogel, “Family Structure, Family Stability and Outcomes of Five-Year-Old Children”, Families, Relationships and Societies 1, 1 (2012): 43–61; Kelly Musick and Ann Meier, “Are Both Parents Always Better than One? Parental Conflict and Young Adult Well-Being”, Social Science Research 39, 5 (2010): 814–30; P. Fomby and A.J. Cherlin, “Family Instability and Child Well-Being”, American Sociological Review 72, 2 (2007): 181–204.

17 Sundaresh Menon, Speech at Conference on At-Risk Youth 2015, at http://www.supremecourt.gov.sg/Data/Editor/Documents/Achieving_Connecting_and_Thriving_031115.pdf

18 Gus Martin, Juvenile Justice Processes and Systems, 1st edn (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005).

19 National Youth Council, National Youth Survey 2013.

20 Ministry of Social and Family Development, State of the Family Report 2004 (Singapore: Ministry of Social and Family Development), at https://www.msf.gov.sg/research-and-data/Research-and-Statistics/Pages/State-of-the-Family-Reports.aspx

21 Philip Graham, emeritus professor of Child Psychiatry at the Institute of Child Health, London, classifies society’s individuals into three main categories: (i) non-problematic conformists (the majority); (ii) non-problematic non-conformists (a conspicuous minority); and (iii) the problematic minority. Philip Graham, The End of Adolescence, 1st edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

22 R.N. Butler, “Age-Ism: Another Form of Bigotry”, The Gerontologist 9,4 (Part 1) (1969): 243–6.

23 J. Wyn and R White, Rethinking Youth, 1st edn (London: Sage, 1997); Susie Weller, “‘Teach Us Something Useful’: Contested Spaces of Teenagers’ Citizenship”, Space and Polity 7, 2 (2003): 153–71.

24 Arnoud de Meyer, “From Start-Ups to Scale-Ups”, The Straits Times, 13 August 2016, at http://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/fromstart-ups-to-scale-ups; Angela Teng, “Starting Up: The Rise of the Singaporean Entrepreneur”, TODAY, 16 January 2016, at http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/starting-up-therise-of/2431670.html

25 Sasha Lekach, “A Singapore Teenager Created a Prezi for Trump, Because Slideshows Are the Worst”, Mashable.com, 19 November 2016, at http://mashable.com/2016/11/18/singapore-teen-trumpcampaign-presentation/#6A8g2Jl9_Sqw

26 National Youth Council, The State of Youth in Singapore 2014 (Singapore: National Youth Council, 2014); Kenneth Cheng, "More Young People Take to Volunteerism", Todayonline, 14 December 2013, at http://www.todayonline.com/singapore/more-young-peopletake-volunteerism.

27 Lea Lane, “Are Millennial Travel Trends Shifting in 2016?”, Forbes, 15 January 2016, at http://www.forbes.com/sites/lealane/2016/01/15/are-millennial-travel-trends-shifting-in-2016-youll-besurprised/#5a34671d5c98

28 Olivia Ho, “This Clean Water Device Creates a Tap from a Backpack, and It’s Saving Lives”, Huffington Post, 20 June 2015, at http://www. huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/20/fieldtrate-lite-water-filtration-_n_7624560.html

29 Desiree Yang, “Stepping Up to Help the Needy”, SMU blog, 3 August 2016, at http://blog.smu.edu.sg/2016/08/03/stepping-up-to-help-theneedy

30 RBS Group, “Growing Appetite among Young People for Social Enterprise”, UnLtd, at https://unltd.org.uk/2013/06/10/growingappetite-among-young-people-for-social-enterprise; Alexandra Wilson, “Meet The 30 Under 30 Social Entrepreneurs Changing Europe in 2017”, Forbes, 15 January 2017, at http://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandrawilson1/2017/01/15/30-under-30-socialentrepreneurs-europe-2017/#79a796942458

31 The Aspirations of Young Singaporean Adults dialogue, held on 14 February 2015, is an example of public dialogues that make a conscious effort to seek to hear and understand the opinions and policy needs of young people. See Sonny Wee, “Top Concerns of Young Adult Singaporeans”, PAP News, at http://news.pap.org.sg/news-and-commentaries/commentaries/top-concerns-young-adultsingaporeans

32 UNESCO, “What Do We Mean By Youth?”, UNESCO website, at http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/youth/youth-definition

33 Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth, “Overview”, MCCY website, at https://www.mccy.gov.sg/en/Topics/Youth/Articles/Overview.aspx

34 Richard Fry, “Millennials Overtake Baby Boomers as America’s Largest Generation”, Pew Research Center, 25 April 2016, at http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/25/millennialsovertake-baby-boomers

35 Joel Stein, “Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation”, TIME, 20 May 2013, at http://time.com/247/millennials-the-me-me-me-generation;Jean M. Twenge, Generation Me— Revised and Updated: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled—and More Miserable Than Ever Before (New York: Atria Books, 2014).

|

Shee Siewying was a Research Assistant at SMU’s School of Social Sciences and the Lien Centre for Social Innovation. During this time, she conducted research on food poverty in Singapore and was an Editorial Assistant for Social Space. An Honours graduate in Social Sciences from the National University of Singapore, Siewying is passionate about cultural geography and food studies, as well as identity politics and geopolitics. In her spare time, she seeks pleasure in books, music, writing, volunteering for local food distribution programmes and discovering new cultures around the world. She can be reached at siewying1005@gmail.com |

Comments