By Harah Chon and Christy Davis

The 21st century is defined by rapid change. From technology and changing power dynamics to social issues, today’s complexities call for a renewed focus and attention towards our environments, economies and culture. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted our daily routines and impacted each of us in a myriad of ways. As we shift from our present situation to a post-COVID world, we can begin imagining a new, contemporary form of community that is not inherited but collectively designed, built and nurtured.

![]()

Responding to the pandemic has, in so many ways, brought out the best of us. Singaporeans gave in record sums to charity through online donation platforms in 2020. In spite of this, there is still an emphasis on individual wants, needs and comforts. Our ability to tackle today’s social challenges requires that we consider the values defining our individual and collective responsibilities. Making the mindset shift from “me” to “we” allows for the design of new behavioural patterns to produce more meaningful perspectives, courses of action, and impactful change.

21st-Century Complexity

The world is facing new challenges that are marked by the changing demands of the 21st century, presenting new degrees of complexity that lead to an increasingly intangible world. Advances in technologies impact many aspects of human life, calling for a more humane and collaborative shift that considers the needs of people and society. This calls for the development of future actions, addressing the tensions produced across the dimensions of capital, technology, change and disruption.

Social, human and economic capital: The ever-changing social, human and economic needs create new contexts and measures for human activity. What is the value of this capital and how can it evolve to produce resilience and robustness?

People + Technology: Advancements in technology require human understanding and new capabilities in the adoption of processes and systems. What is the future role of technology and how can it be more appropriately designed within the constraints of human needs?

Speed of Change: As a temporal concept, change is an inevitable condition responding to a series of moments that contemplate the present. Against the rapid nature of change, what are ways to develop more versatility in response to growing uncertainty and complexity?

Disruption: The concept of disruption has been widely adopted as a strategy to combat and tackle complex issues and problems. While disruptions are designed and executed to positively respond to challenges, they often produce unfavourable outcomes and implications. How can disruptions be more positive, constructive and transformative?

![]()

The changing values and measures of capital, the symbiotic relationship between people and technology, the temporality of change, and the role of disruption pose challenges and dilemmas requiring new ways to respond, adapt and enact. A significant shift in perspective is necessary to inculcate and support the new requirements and capabilities brought on by 21st-century complexity..

Today’s social issues require a greater degree of collaboration and participation to better analyse and facilitate change. Different levels of expertise are needed to demarcate the boundaries of issues, allowing for a more comprehensive examination of symptoms to produce more effective and sustainable solutions. By developing more sensitivity to local culture and needs, more focused approaches can be scaled and optimised for larger impact.

Lessons from the Art and Science of Design

Design is both a practice of making and a way of thinking. It responds to continual change, ambiguity and complexity through forming unique perspectives, developing iterative processes, and producing replicable tools and methods. The ability to address today’s social challenges requires a new set of skills to creatively and effectively introduce valuable impact. This marks a significant shift for the 21st-century designer from a focus on activities and outcomes, to designing for people and societal issues.

![]()

Against the pace of change and accompanying ambiguity facing the world, design presents a way of rethinking and reimagining individual action to create more flexibility for connecting with our communities and societies. We have the ability to create a space where creativity can result in new social innovations for good; Ezio Manzini shares stories of social innovation that illustrate how, even in these challenging times, a better society is possible.

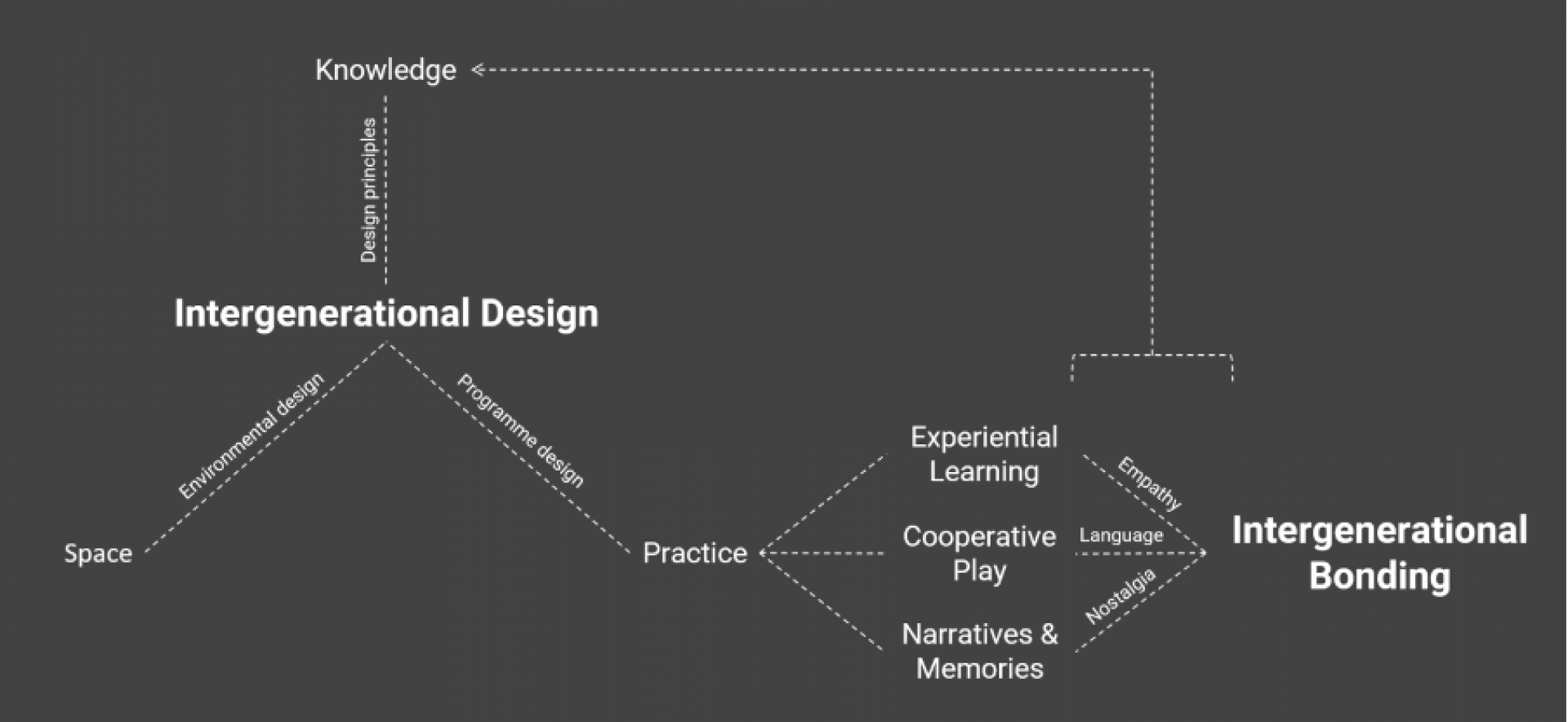

He presents three conditions for producing a contemporary form of community that is not inherited, but collectively designed and built. Fluidity allows for more flexibility in discovering problems and adapting to solutions against a world of rapid transformation, openness leads to new possibilities through encountering and confronting different ideas and purposes, and lightness produces new community value through promoting inclusivity and informal interactions. This notion of the contemporary community presents the possibility of everyday social innovations, such as Sin Shiu Heng’s framework for intergenerational design, creates a participatory ecosystem in which projects can be developed and transformed to generate new conversations for future actions. Manzini calls this “project-centred democracy".

Fig. 1 “Intergenerational Design Framework” by Sin Shiu Heng, MA Design '20

Design, by nature, is human-centred with a focus on developing interventions and solutions to improve the quality of everyday human experiences. In recent decades, design has provided numerous tools and methodologies to facilitate more meaningful interactions and produce lasting impact—in effect, encouraging the mindset shift needed to move from “me” to “we".

Under the research theme of Citizen Designer, recent LASALLE College of the Arts MA Design graduates have developed research projects that fit into Manzini’s concept of project-centred democracy.

“Enabling Collaborative Turns for Design Workgroups” by Sze Yunn Seah, MA Design '20

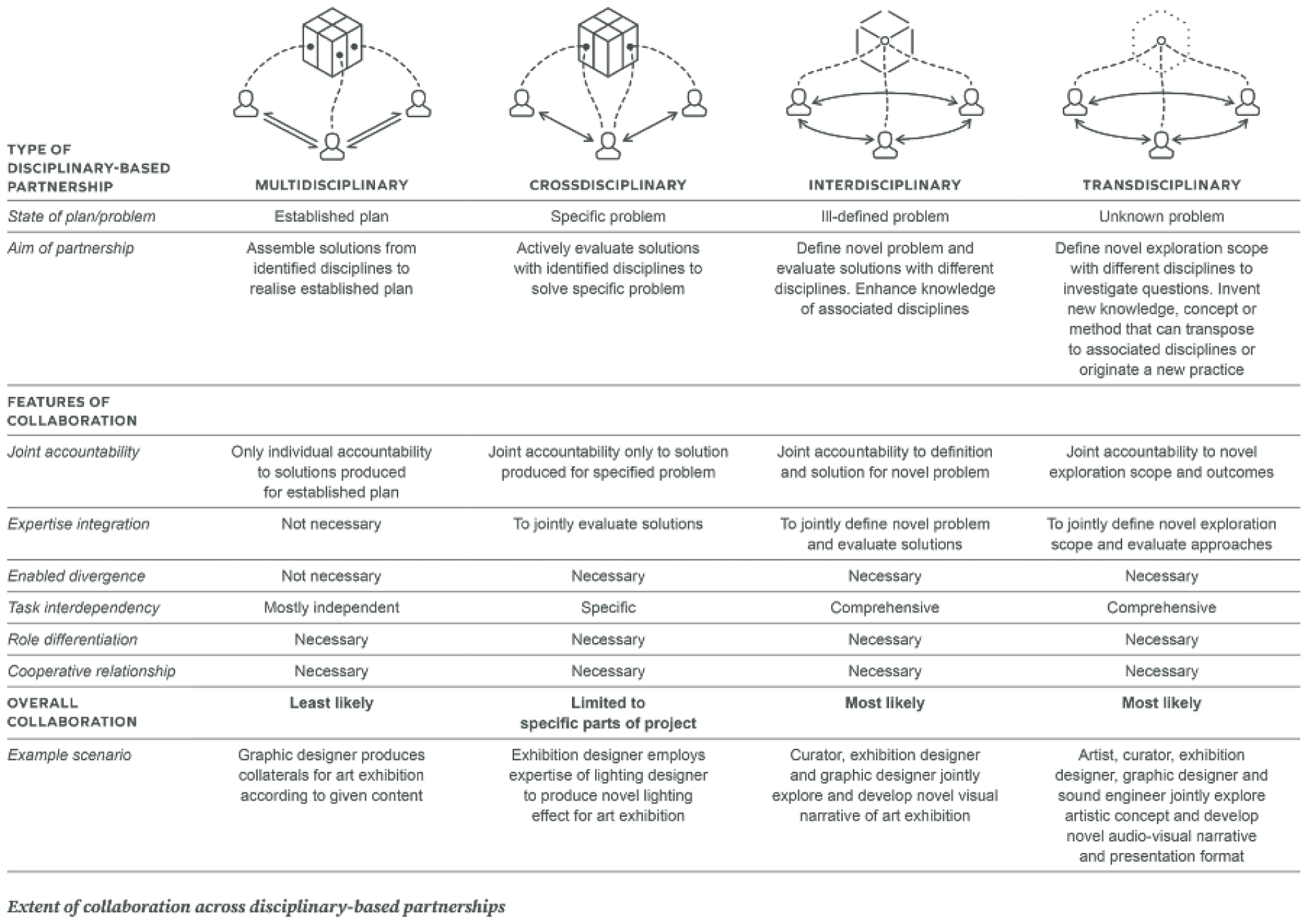

Today’s working groups are no longer defined by a single discipline or institution of practice. As our societal problems increase in uncertainty and complexity, they require a convergence of different skills, multiple perspectives, and generative forms of knowledge. Collaborative Turns emphasise the role of conversation within working groups to reach shared understandings, arrive at agreed actions, and produce more innovative and purposeful solutions. A framework of practice provides a guideline to organise partnerships, outlining the disciplinary implications of collaborative working groups.

Fig. 2 “Extent of Collaboration Framework” by Sze Yunn Seah, MA Design '20

The future will require more interdisciplinary knowledge as we shift from individual to collective modes of thinking and acting. This calls for the development of new terminology that is more relevant and clearly explicated within the contexts of use. The implementation of a shared language in future working groups will foster more meaningful dialogue to achieve a better alignment of objectives and values to support the tenets of project-centred democracy.

Moving Forward Together

The 21st century has introduced massive change across all levels of human life, technologies and systems. This has resulted in a reactive culture of adjusting and adapting, rather than redefining and disrupting. As we reimagine the future of social innovation, there is a pressing need to create new forms of participation across different contexts and practices; working together and community-based activities help set the tone for bottom-up social change.

Generative Systems to Generative Societies

The increasingly complex, vague and ambiguous world demands an examination of generativity as a fundamental concept for future-proofing. Redefining systems from the individual to community-levels of interaction allows for project-centric democracy to emerge, as smaller and locally-situated projects begin to contribute to larger societal shifts. This leads future change from generative systems to the creation of generative societies.

![]()

As Aaron Maniam wrote in his 2017 essay "Beyond a scarcity mindset: A letter from my future self":

"...resources like data, networks and relationships, are ‘generative’ rather than scarce. The more they are used, the more of each resource we have; the better it becomes. Data begets more data, knowledge catalyses new knowledge, and the strong social capital underpinning relationships benefits from being carefully tended, much like gardens generate new life from periodic pruning."

Leading Social Change

So where do we begin? For several undergraduate students who joined the Lien Centre for Social Innovation's #CurbYourConsumption movement, change begins from a single step and shared purpose. The students, who made a conscious effort to decrease their reliance on social media, electricity, water, meat, shopping and single-use plastics, found that making sustainable lifestyle tweaks was both easy and meaningful.

![]()

The global pandemic has indeed presented new challenges while uncovering the systemic issues that are deeply rooted in our culture and society. As we begin to transition into the post-pandemic era, there is an opportunity to regroup as a society and re-evaluate the significance of building socially responsible and mindful practices. This critical period will require a new outlook on how we define our problem spaces, facilitate community-level involvement and multi-stakeholder interactions, produce appropriate terminology for building future dialogues, and develop generative actions to strengthen our commitment to society.

Images via rawpixel.

|

Harah Chon is a Korean-American design practitioner, researcher and educator. She began her professional career in New York as a fashion designer at Ralph Lauren before pursuing postgraduate studies in Hong Kong. Dr Chon holds a PhD in Design Epistemology, through which she examined the ontological structures of knowledge representation to produce a culture-based taxonomy of design knowledge. Her current research activities focus on design theory and philosophy across the themes of collaborative design frameworks, disruptive approaches to interdisciplinary design, intangible culture and heritage, and knowledge transference. She advocates the furthering of discourses on design and cultural sustainability, social design and design knowledge. She can be reached at harah.chon@lasalle.edu.sg |

|

Christy Davis is Executive Director of the Lien Centre for Social Innovation at the Singapore Management University. She brings more than 25 years of experience across the private, public and social sectors. Prior to joining the Centre, Christy founded Asia P3 Hub, a multi-sector partnership hub hosted by World Vision International, whose aim is to tackle effects of poverty and collectively create solutions to benefit families and communities. She was part of the first cohort to graduate from the Singapore Management University’s Master of Tri-Sector Collaboration in 2015, and also holds an Executive MBA from Sasin Graduate School of Business Administration, Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. Originally from the US, Christy has made her home across four countries in the Asia Pacific for 30 years. She can be reached at christydavis@smu.edu.sg |

Comments