By Gabrielle Cheong

Tangled within the warehouses of Eunos Industrial Park stands a shuttered doorway. Abandoned and unassuming, it looks like a de facto parking lot or a holding space for bricks and metal sheets. This morning, as I stood before Block 1010, Unit 01-24, I was excited to have arrived at the workplace of Singapore’s last Malay carpenters. In the little research I’d done beforehand, I learned of their immense pride in handmaking furniture in an era dominated by giants like IKEA and COURTS. For generations, the carpenters were carving intricate designs onto frames and cupboards for a small but loyal customer base. In the end, eager as I was to find out more about their work, I did not get the opportunity to meet them. My hopes for a face-to-face interview were dashed when a lady from the neighbouring unit informed me that their workshop had closed for good since two years ago. “They couldn’t pay the rent,” she said with a nonchalant shrug, even before I could ask why.

The Malay carpenters’ workshop never had a signboard to mark their presence. In the wake of their departure, their names have barely left a trace on the record.

Former workspace of Singapore's last Malay carpenters; photo by Gabrielle Cheong.

Traditional Craftspeople: Singapore’s Invisible Lifeblood

UNESCO defines “crafts” and “artisanal products” as any handmade item, where “the direct manual contribution of the artisan remains the most substantial component of the finished product.” They can be utilitarian (fulfilling a functional purpose, like custom-made furniture) or aesthetic (like pottery). More significantly, crafts and artisanal products are an important source of income and livelihood for their makers. According to author Tina Sim, early Singaporean society was gradually and painstakingly shaped by the hands of these artisans. In her children’s book, Once Upon A Singapore…Traders , she explains how traditional trades—including crafts—started as simple businesses set up by poor immigrants from China, India, Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula. Rattan weavers, clog-makers, smiths, and other craftspeople supplied their communities with various necessities, forming over time the core of everyday life in the new city-state. Yet the role that these humble, everyday craftspeople played in nation-building does not feature prominently, if at all, in Singapore’s history books.

Photo by Jansel Ferma via Pexels.

Here’s another fun fact supplied by Mayur Singh, co-founder of Coopita and The Green Collective: back in the day, Singapore was a rubber plantation hub of sorts. “When rubber’s taken out of the plant, you need pots to contain the rubber sap, and we were once considered a good hub for pottery-making,” he said. “If you meet old potters here, only they will tell you about it. It’s not documented anywhere.” But here we are, in 2019. Decades of modernisation have changed Singapore’s priorities, driving our focus from labour-intensive manufacturing to the more lucrative “skills-based” or “high-tech” industries. In an age where mass production gets us almost everything we need at a low cost, there is far less reliance on the slower, more intimate processes of artisanal labour. As such, craftspeople and their ateliers have retreated from the main streets into the depths of industrial parks and remote shophouses. This leads me to wonder: with our artisans shunted to the periphery of societal consciousness, and their crafts and handiwork relegated to the status of “vanishing trades” and “the informal sector”, how soon will both the people and products become relics of a distant past?

Hanging by a (Paper) Thin Thread

Mr Toh, co-owner of Associated Handicrafts Co., a paper-effigy-making business, is fully aware of the way modern society views the “old vanguard”. He’s been in the trade for 69 years since inheriting the business from his father. During my visit, he gave me free rein of his workshop, occasionally taking a break from cutting and gluing to explain some of his older projects. These ranged from towering mansions precariously supported by sticks, to brightly coloured horse heads dangling from the ceiling, to accessories like printouts of modern toilets. We also pored over newspaper clippings of his past interviews, and old features about him and other traditional craftspeople.

Paper effigy dolls in Mr Toh's workshop; photo by Gabrielle Cheong.

“All of us left are the old guys, there are no successors,” Mr Toh said, staring wistfully out the door at the surrounding warehouses. “Nowadays young people want to brew coffee—no one wants to do hard labour.” I then asked where he saw himself and this trade in the near future, and he spoke of plans to sell the business within the next two years. His replies continued to be pessimistic when I broached the possibility of hiring new blood: “What can educated people do to help? These days nobody is trustworthy—after they finish studying they go abroad or want to start their own businesses. Even if you hired them, they won’t stay with you long.” He also seemed to interpret the dip in demand for his products as a sign that the modern world is moving on without niche craftsmen like himself: “Now everyone’s religion is different. Not everyone worships [the same] gods or becomes a Taoist. When people come to my workshop, they’re here to have to look…none of this really means anything to them.”

Paper effigy house in Mr Toh's workshop; photo by Gabrielle Cheong.

A Walk in Their Shoes

Capal-maker Haji Ahmad has been feeling the disjunct between his own trade and that of rapidly modernising Singapore. In his interview with academic Margaret Sullivan, he shared that he’d been making these unique leather sandals—worn as part of the Malay traditional dress—ever since he was 18, in a long career marked by much hardship, including the Japanese occupation of Singapore. Over decades, he kept his business going in his own slow and steady way, saving little by little, and keeping busy. Yet today, none of Haji’s nine children or numerous grandchildren is willing to continue his capal-making legacy. “[My children and grandchildren] hear about jobs at [supermarket] Cold Storage and run there…or they want to be drivers,” he said of their employment preferences. What, then, of his customer base? Is there still demand for this “older” style of footwear? Yes, he claimed, though his clients are predominantly elderly Malays. “It’s mainly the older people who wear capal now” since, according to him, younger people prefer wearing shoes or Japanese-style slippers.

Capal, leather footwear that is part of the traditional Malay dress; photo by Ridzuan via Flickr.

Traditional Crafts: Whither the Relevance?

If we knew where to look—and if we managed to find them—there remain a number of veteran craftspeople like Mr Toh and Haji Ahmad in Singapore. They range from Chinese seal carvers and Indian goldsmiths, to makers of the ubiquitous red banners we see during the Lunar New Year. Yet what Mr Toh and Haji Ahmad’s stories reveal is the undeniable reality of dwindling market demand. They tell a similar tale involving declining interest in the trade, a lack of succession, and the looming threat of their life’s work going entirely extinct.

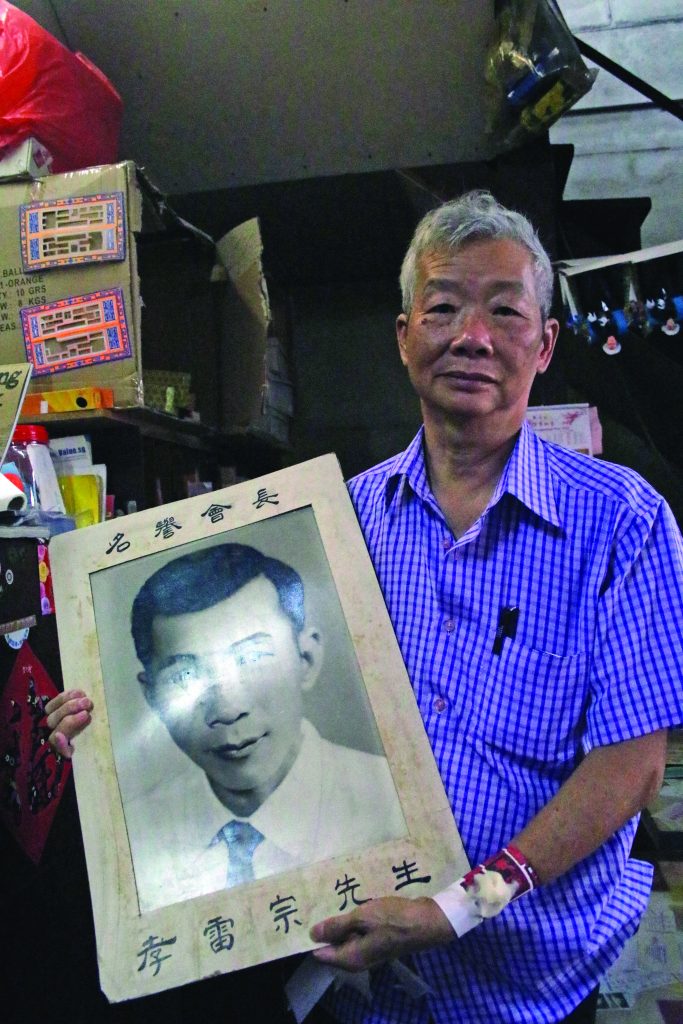

Mr Toh holding up an old photograph; image by Gabrielle Cheong.

Moreover, the practitioners themselves seem to have adopted the pragmatic view that younger generations are better off taking higher-paying jobs. Mr Toh admitted that he encouraged any young people visiting his workshop to “study hard so they don’t end up doing hard labour”, while Haji recognised the diminishing need for his products in the fact that few people under the age of 40 still wear capal, and none in the family are interested in continuing his legacy.

Old Practices, New Attitudes

In my view, if a revival is what this industry needs, the discussion on artisanship needs to evolve beyond the realm of heritage and cultural preservation. To survive modernisation, should we not first challenge antiquated mindsets about its place and relevance in 21st-century Singapore? When I raised these points with Associate Professor Jesvin Yeo of NTU’s School of Art, Design and Media, she concurred. She went on to recount an incident she personally witnessed, which, she believed, exposed Singaporeans’ biased and compartmentalised view of artisanship. Prof Yeo was at the National Museum admiring a display by a craftsman who specialises in making giant joss sticks. “He was teaching visitors how to use the wood clay from his joss sticks to make figurines, sparking the interest of a young boy. However, when the boy had tried to touch the display, his mother pulled him away, saying, ‘Don’t touch it! It’s a religious item!’" The mother’s extreme reaction towards this so-called “religious item”—in fact, just cinnamon wood bark—was coming from a traditional mindset that crafts are tied to cultural practices of a bygone era. But, Prof Yeo claims, if we’re able to shift our view of artisanship from that of products to artistry—and the value that brings—there can be room for innovation.

Joss stick art installation; photo by WKiang Liew via Flickr.

She described several of her projects, in which she took a deep dive into the trade and worked closely with traditional artisans. These experiences in turn inspired her to create more contemporary products, such as a sun chair she built in the style of traditional Chinese lanterns: “When the artisan told me his lanterns could last in the sun for 10 years, I wondered if we could use the same process to come up with something more useful to society. Eventually, after one and a half years of training, learning traditional methods of cooking the glue to hold the lantern and paper together, and experimenting ways to keep the chair from turning yellow, Prof Yeo showcased her work at the DMY International Design Festival. On an even larger scale, traditional craftspeople can be an unexpected source of help in bringing about technological breakthroughs. Mayur Singh cited the case where Bolivian children suffering from congenital heart problems were indirectly saved by Aymara tribe’s knitting techniques. Kids’ hearts are small and challenging to operate on, but weavers worked with cardiologist Franz Freudenthal to create a small occlude made of a super-elastic metal, which makes its way into the heart, spreads, and stops the hole. “Just imagine if these weavers weren’t there, this problem might never have been solved,” Singh said.

Start with Education

In the past five to ten years, there’s been a people-led “heritage movement” to preserve facets of Singapore’s cultural legacy, mainly through documenting and raising awareness about traditional crafts and artisanship. But in my view, the more crucial step to elevating traditional crafts’ position in society is education. Growing up, the average Singaporean has little to no direct exposure to traditional craftsmanship or contact with artisans over the course of their education, work or leisure. Fewer still enter this trade unless it’s a family business.

Photo via Pexels.

Living in a modern world where many things come easily, artisanship additionally offers key values such as “patience, self-expression, an eye for detail, and taking pride in one’s work”, as outlined in Yeo's book, Vanishing Crafts. But at present, school curricula is still mostly dominated by STEM subjects, and children's lives are considerably removed from traditional crafts. As Singapore looks to enhance its education model in favour of something more holistic, perhaps we should consider offering artisanal crafts-making as a credit-bearing subject to both incentivise learning and impress upon the youth its potential social and economic value. Prof Yeo is in support of nurturing this appreciation from the get-go. “Kids generally love fieldtrips to ateliers and workshops, and we should talk about and expose them to artisanship from pre-school or primary school age.” Ultimately, she posited, raising a generation of children who are interested in traditional crafts will build demand for the goods and artistry. “Once we know how to appreciate the craft—and the crafts—we’ll be more willing to pay money for it.”

Improve Platforms, Build Capacity

In the meantime, with more coordinated initiatives to help them adapt and innovate designs and methods, we can support traditional craftspeople in their struggle to stay relevant. Platforms like The General Company—though catering more to younger artisans than the older players—are models of how we can support local craftspeople by offering spaces to co-create, collaborate, market their wares, and connect them with bigger, more established brands. However, Singh warns, it is critical to first understand how the business works, and bridge the gaps in the supply chain. “The process of getting crafts to marketplace involves the person who makes the product, the person who conceptualises it, and the person who sells it,” he explained. “All three parties have to come together for craftsmanship to be successful. At the moment, most work in silos.” In other words, as we seek to revitalise the sector, we also need to examine the current structure of Singapore’s crafts production. Only then can we work towards developing an ecosystem embodying greater synergies between the maker, the designer and the salesperson.

Photo by Erwin Soo via Wikimedia Commons.

The fading sounds of clanging, hammering, lorry engines and scratchy radio transmissions accompanied me as I exited the space that was once the Malay carpenters’ workshop. Someday, I thought, such sounds might be replaced by silence as more ateliers retreat into oblivion.

Photo by Fancycrave.com via Pexels.

Photo by Fancycrave.com via Pexels.

While one can hope and believe that will not be the case, convictions will only get us so far. Craftspeople are part of a vanguard that has silently but richly contributed to Singapore. Only if we take active steps to honour and sustain their legacy, will we secure their place in our past, present and future too.

|

Gabrielle Cheong was a 2019 Summer Associate (Editorial) at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation. She is a rising junior at Yale-NUS College, majoring in History. Gabrielle likes to deconstruct the narratives behind the culture and policies that shape our daily lives, and hopes to pursue a career in policy research. Previously, she volunteered with the Meet-the-People Sessions, the National Parks Board at Pulau Ubin, and was a member of the Community for Advocacy and Political Education (CAPE). She can be reached at gabrielle.cheong@u.yale-nus.edu.sg |

Comments