By Martina Mettgenberg Lemière and Kevin Teo

Grantmakers and social investors (funders) are successful only to the extent whereby their grantee or investee organisations—collectively known as social purpose organisations (SPOs)—achieve sustainable social impact. More often than not, we hear of SPOs caught in the daily grind of responding to urgent beneficiary needs, and not having the opportunity to introduce more effective practices.

The foundation for sustainable social impact arises through engagement from grantmakers and social investors in capacity-building and impact assessment of the SPOs. Capacity-building and impact assessment are two key venture philanthropy (VP) practices.

In the last year, the Asian Venture Philanthropy Network (AVPN) documented trends in these two areas, with the objectives of helping novices acquire best practices in a shorter time, and enabling seasoned practitioners to share their knowledge and develop new insights.

Building Capacity of SPOs to Increase Effectiveness

Making capacity-building effective involves a few steps. First, it is critical to understand what is truly required for the SPO to build its sustainable social impact. After funders understand the needs of the SPO, the second step is to delineate how support can be organised. For some funders, such as Social Ventures Hong Kong, they do this with in-house teams. Others bring in external service providers—paid, pro-bono, or skillsbased volunteers. When funders work with skills-based volunteers, they also often bring in an external provider to help them manage these, e.g. the Singaporean intermediary Empact or the Indian organisation Toolbox Foundation.

As can be seen from most case studies in AVPN’s collection, the main trend is to manage service provision in-house with skills-based volunteers, rather than developing in-house teams or working with service providers. A final core step to capacity-building is assessing whether it has made a difference to the investee. This remains in the early stages with some efforts having been made by private entities offering their system for a fee.

The impact assessment is similar to organisational impact assessment insofar as the funder has to develop a theory of change, and collect and analyse the data they think they need. From our case studies, funders tend to employ three methods to this end: i) measuring the organisation’s progress in total and seeing the entire impact as an outcome of the capacity-building; ii) measuring what is supposed be changed before and after; and iii) measuring the extent to which the organisation has built critical capabilities.

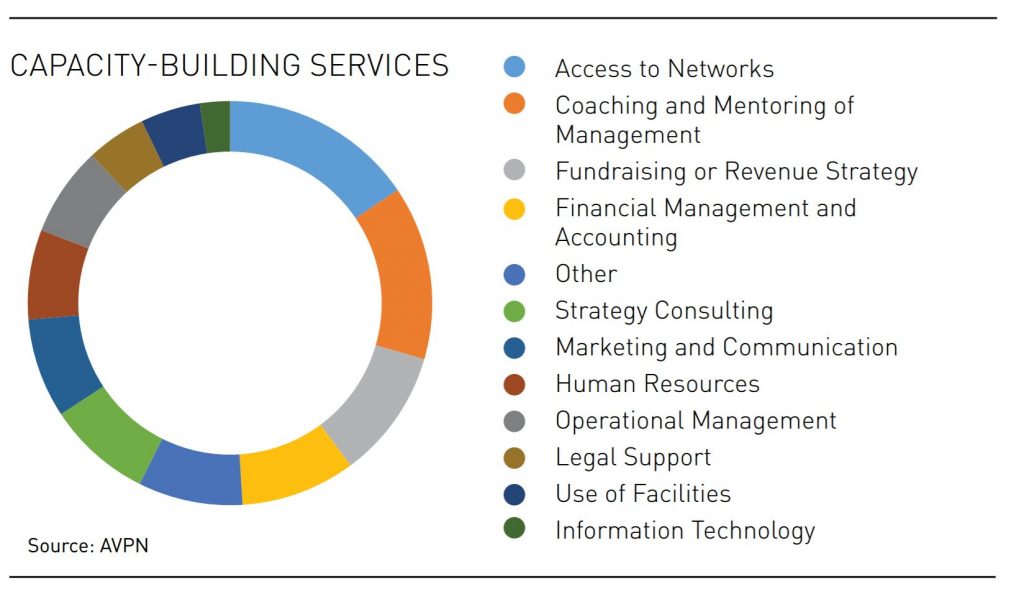

With assessing impact of the capacity-building, most funders close the loop to understand what works and adjust their offerings. In a recent AVPN membership survey of 111 members on venture philanthropy practices, the capacitybuilding services offered most often included access to networks, coaching and mentoring, fundraising and revenue strategy, and financial management and accounting.

Assessing Impact: Another Core Venture Philanthropy Practice

In that same survey, 72 per cent of the 111 AVPN members measured impact at various intervals through the engagement. There are now many methodologies in impact assessment ranging in complexity and robustness. Next to offering an analysis of the major approaches in which framework to choose, how to get started, how to implement and finally how to present the findings, we recently interviewed 13 leading practitioners in Asia about their approach for our Effective Guide to Impact Assessment. Two major trends from the literature review and practitioner portraits are: standardisation, customisation and comparability; and usage for performance management and external presentation.

Comparability of solutions can be the stated aim of impact assessment. However, most of the organisations in our sample felt they were unable to compare organisations’ results as each had a different business model to address social issues and therefore had different indicators and outcomes. Even within the portfolio of one social investor, standardising measurement and indicators was often impossible, and every social organisation was measured in a highly customised way and on its own merit. Some social investors, such as Nexus for Development, Microsoft Japan and Epic Foundation, were able to standardise and compare for a few reasons. Nexus for Development requires the measurement of carbon efficiency and applies international standards. Microsoft Japan fine-tuned its Social Return on Investment (SROI) approach over a number of years and is now able to compare different interventions in the same field. Epic Foundation already selects organisations in the due diligence phase according to 15 parameters and continues monitoring these as impact. These three approaches allow comparability.

Interestingly, we also found that many social investors use impact assessment mostly for performance management and only some data for external presentation and reporting to funders, such as public donors or investors into their funds. This is perhaps unsurprising, but worth highlighting as impact assessment data can be seen as a marketing tool or “vanity metrics” and, like financial data, can therefore be a victim of manipulation. Using it as performance metrics indicates that organisations rely on it behind closed doors, which suggests that they are interested to learn about what works and what does not.

While we may be impatient to see results and compare, this curiosity is one of the strongest findings in our research on impact assessment and certainly one of the core areas of venture philanthropy.

Capacity-Building and Impact Assessment: Two Out of Five Core Practices in Venture Philanthropy

Venture philanthropy’s main focus is that of an engaged relationship. On the spectrum between investing and donating, VP occupies both, as well as the entire middle ground of convertible finance options, grants with capacity-building support, and wealth allocations in terms of investment.

Venture Philanthropy Organisations (VPOs) range from foundations, overfunds, family offices and angel investors, to corporations and governmental sovereign wealth funds. Similarly in terms of target of investment, there is great flexibility. VPOs can invest in any business model from non-profit and donations-based over revenue-based to supply chain corporates. For instance, a quick look at AVPN’s membership reveals the diversity of resource providers and their funding targets. At the same time, not all funders are VPOs, nor would they consider their activities to be venture philanthropy. AVPN considers a VPO as one that practises capacity-building and impact assessment, as well as pre-engagement, portfolio management and multi-sector collaboration.

VPOs are different from other funders in that they are engaged for the long term and emphasise the partnership with SPOs in creating impact. This is different from writing a cheque or investing, agreeing on the term sheet, and then sitting in quarterly board meetings. Both of these modes are fine, but we found that it is more effective, when creating sustainable social impact, to co-create social impact closely with the SPO.

In the pre-engagement phase, funders develop their mission, strategy and a potential deal pipeline. They then use this to raise funds from other funders as well as to shortlist organisations according to this. After investing, they work closely with the organisation to help them make the most of the finances disbursed, as well as increase the organisation’s skill level in meeting its social mission. The impact assessment practice already starts in the pre-engagement phase, where the social investor and the investee negotiate their vision for impact and what can be achieved. Fundamentally this carries through during the engagement, and also allows the investee organisation to benefit and learn from it in the long run, even after this investment period has ended.

Portfolio management is predominantly done on the side of the funder, but builds on the areas of impact assessment and influences pre-engagement, capacity-building and multi-sector collaboration. Beyond risk and return equations in the financial realm of portfolio management, VP portfolio management needs to account for social mission achievement, and different funders have different strategies.

Finally, multi-sector collaboration acknowledges that most funders have to work across sectors and with many different stakeholders to see their solutions come to fruition and carried by more people than themselves.

Together, these five practices span the entire arc of social investing—the most central of which are capacity-building and impact assessment.

Pulling Together Various Silos to Build Up Expertise around the Capability Development Model (CDM)

To increase the efficiency of AVPN members' efforts to build social impact, AVPN is holding a number of events, workshops and learning labs, the largest of which being the AVPN Conference.

Attended in 2016 by 650 participants in Hong Kong, it brought together government officials, funders from impact investing funds, foundations, VP funds and others, corporates and multilaterals and non-VP funders to discuss the trends in social investing. Spread over 24 sessions, the talks covered all five areas of VP, as well as sector and country focus or hot topics including faith-based philanthropy, philanthropy and sustainable development goals (SDGs), and human capital in social investing.

Other initiatives, e.g. the Asia Policy Dialogue and workshops in capacity-building, are more focused on sharing specific knowledge in such areas as how to foster the social economy through policy or to discuss with experts and peers selected best practices of capacity-building. These are offered throughout the year and provide a platform for engaging all stakeholders within the ecosystem of social investing. As social issues across the globe become increasingly complex and multifaceted, and faced with limited resources, funders have little choice but to increase the effectiveness of SPOs to address these issues. Focusing on capacity-building and impact assessment are two key areas that can provide significant gains on effectiveness.

Across Asia, AVPN is witnessing a burgeoning community of practitioners who are embracing this mindset and working collaboratively to deliver sustainable social impact.

Martina MettgenbergLemière is Head of Insights and Capacity-Building at the Asian Venture Philanthropy Network (AVPN). She builds on a decade of experience in leading applied research for businesses and non-profits with a focus on human capital, education and impact. Most recently in Singapore, she led projects at INSEAD and the Human Capital Leadership Institute, and mentored students at the micro-business school Aidha. Previously, she worked in business research and consulting in India, and taught at the Universities of Manchester and Sussex. She can be reached at martina@avpn.asia

Kevin Teo is Managing Director of AVPN’s Knowledge Centre. His previous appointments include: Co-Founder of Volans, a Social Innovation company with offices in London and Singapore; Head of East and Southeast Asia at the Schwab Foundation of Social Entrepreneurship; and Global Leadership Fellow at the World Economic Forum. Kevin is a Trustee of the Southeast Asian Service Leadership Network (SEALNet), a non-profit he co-founded in 2004, and sits on the evaluation panel of the Ministry of Social and Family Development’s ComCare Social Enterprise fund. He can be reached at kevin@avpn.asia

Comments