Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” The only issue is, not everyone has access to education.

I was born in the 1980s in suburban Sydney, Australia. A few decades ago, my great grandparents moved from China to Malaysia during a time of famine, and my parents later immigrated to Australia before I was born. Growing up, I attended a public school in Sydney with a good reputation. On my first day of school, I remember sitting next to a boy named Roger who, according to our class teacher, Mrs Pickering, was unable to see colours. My job was thus to help Roger pick out the right coloured pencils during the colouring activities. For grass, I would hand him the green pencil; for the sky, the blue one.

That year, Roger and Mrs Pickering taught me a valuable lesson about inclusion. I learned that not everyone is like me, and that some people have to do things differently—and yet, with a little bit of help from others, those people can join in with everyone else. That experience also made me realise how privileged I was and am. I knew that if my family had not emigrated twice, and made personal sacrifices along the way, I would not be in Sydney, at school, and helping a classmate with his coloured pencils.

However, not every child is as fortunate as I was to receive a good education, and, in Roger’s case, blessed with an inclusive teacher like Mrs Pickering. Ouk Ling was one such example (see boxed story: “Ouk Ling’s Story”). Through his plight, I became emphatic about the need to make speech therapy more widely available in Cambodia and elsewhere, and to create greater awareness about this pressing social need.

Talking Points

Communication goes beyond just talking—some people do not speak clearly, or at all, or have problems processing incoming communication. Sufferers of communication disorders are typically children with conditions such as cerebral palsy, Down Syndrome, autism or intellectual disabilities, and they are just as likely to have problems swallowing. Without adequate therapy, they cannot communicate well enough to participate at school, or with their families and communities. Those afflicted by swallowing disorders face an equally uncertain future: instead of travelling to the stomach, swallowed food and liquid can enter their lungs, and they are 13 times more likely than the average person to die from pneumonia at a young age.

OUK LING’S STORY

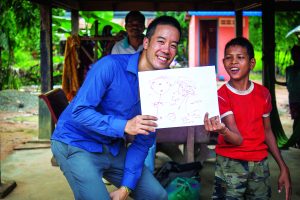

OIC founder Weh Yeoh showing the drawing of 13-year old Ouk Ling In 2012, I met Ouk Ling. A bright boy with an infectious smile, Ling lives with his family in Siem Reap, home to the great temples of Angkor Wat, but also one of the poorest provinces in Cambodia. Ling’s speech is heavily slurred due to cerebral palsy, and as a result, most people in his community assume he is stupid. He therefore has never been given the chance of an education. Ling is one of many such children who, without the support needed, would never attend school and be given a chance to contribute meaningfully to society. I came to know of Ling’s plight through my work with CABDICO1, a small Cambodian NGO that provides services including physiotherapy, social work, home-based education and basic medical care, to help children with disabilities lead more independent lives. During a discussion, my CABDICO colleagues shared that they did not have the requisite knowledge and training in speech therapy to help local children such as Ling. They further identified that as many as 70 per cent of Cambodian youth require speech therapy, but no services were available to address this need. Upon further research, I found that one in 25 Cambodian children do not have access to education2, and as of 2017, the entire country did not have a single Cambodian speech therapist. This meant that there was no university course, no government policy, and virtually no awareness at both community and national level about communication disorders. Needless to say, nothing was being done about this issue. Though Ling’s future looked bleak, I wondered if he might have a shot at a productive life if he received the help needed to speak more clearly. I decided, then, to put my theory to the test, by enlisting the help of several Australian speech therapists to train my CABDICO colleagues in this area. One of those who underwent this training was a lady named Phearom, who went on to administer speech therapy to Ling. Gradually, word by word, sentence by sentence, Ling’s speech improved with Phearom's help. His family began to understand him, and his cheeky personality, previously hidden beneath his communication difficulties, started to emerge. Finally, just months after commencing speech therapy, Ling was able to go to school. Today, at 13, he is not just participating, but excelling. On my most recent visit to Siem Reap, I learned that Ling had come in second in his class. |

Moral Support

Ling’s story demonstrated the power of speech therapy, and its potential to dramatically change a child’s life. However, without a single speech therapist in Cambodia, many children are missing out on a precious education. To this end, I established OIC Cambodia3 in July 2013, as a project under the umbrella of CABDICO, to address the yawning gap in speech therapy in Cambodia. “OIC” stands for that Eureka moment when you suddenly understand something you previously did not, and exclaim, Oh, I see! In a sense, that is very much what speech therapy is about—providing connections and mutual understanding. One of the initial challenges we faced was building a network of support.

In the beginning, I spoke to hundreds of people, from embassies, international NGOs and foundations, to small Cambodian NGOs and individuals. However, more often than not, the meetings would not result in anything tangible. As I considered Ling, and all the other children in need of speech therapy, I wondered how it was possible that so many people had been ignored for so long. Perhaps while the system of international development, charity work, and grant applications assists many people, others still get left behind.

Disability worker Phearom with six-year old Vai Vin

Eventually, I realised that in order to reach these people, we need have creative solutions and/or to create our own system, rather than rely on international development. We thus had to find a way to take OIC forward by ourselves. For a start, we estimated the number of speech therapists Cambodia needed: if we compare the number of speech therapists to the general population, you’d need one speech therapist for every 2,342 people.4 When applied to the Cambodian context, we found that the nation is in need of 6,000 therapists when it effectively had zero.

Next, we considered Cambodia’s high dependency on international aid: an estimated half a billion dollars of aid money enters the country every year, and there are over 3,500 NGOs.5 Many volunteers visit Cambodia regularly to train local communities, but they come and go. When it came to addressing the dearth in speech therapy, we decided that we needed a solution that was infrastructure-focused. Rather than giving a man a fish, or even teaching him to fish, OIC would help Cambodians build their own fishing industry—i.e. grow the profession of speech therapists in the country—with the support of the Cambodian government. To this end, OIC’s work entails designing university courses in speech therapy, running training programmes, creating related jobs, influencing government policy, and ultimately letting speech therapy become a self-sustaining industry.

Means to an End

I believe it is just as important to know why you are doing something before you start doing it, as it is to recognise when you are going to stop doing it. As such, an exit strategy is vital: OIC plans to leave Cambodia in 2030, by which time there will be about 100 local speech therapists employed by the Cambodian government. Although 100 is a far cry from the 6,000 needed to cover the whole nation, the requisite infrastructure will be in place to ensure a continual flow of qualified speech therapists entering the market. And over time, these numbers will keep increasing.

Most non-profit initiatives run on the hamster wheel of getting funding to address a problem, spending the money doing good work, then justifying their work to get more funding. OIC’s funding model, however, is somewhat different since we do not plan to be in Cambodia indefinitely. At present, it is financed by wo key initiatives: Day Without Speech6 and Happy Kids Clinic.7

Weh Yeoh with disability workers in Siem Reap

|

Day Without Speech is an awareness and fundraising campaign taking place in schools, universities and workplaces. It challenges people to give up speaking for a part of their day, to learn what it is like to have a communication difficulty. By accepting this challenge, people learn empathy, mindfulness and creativity. At the end of the day, OIC’s speech therapy volunteers conduct debrief sessions with participants to help them reflect on their experience of not talking during the day. The sponsorship and donations from these participants, and those of their friends and family, help to fund OIC operations in Cambodia. |

Happy Kids Clinic is a private practice in Phnom Penh, Cambodia that provides speech and occupational therapy. This practice allows OIC to generate profit by providing services to the locals that previously did not exist, and raises awareness of the need for speech therapy. With important assessment tools, Happy Kids Clinic shows Cambodians what speech therapy looks like in practice, and helps them to appreciate the value in it. OIC hopes that they would in turn be empowered to champion the cause of speech therapy in future. |

Come April 2017, I will step back from the leadership of OIC. Thereafter, my Cambodian colleague, Pisey Soeun, will assume the position of Executive Director and lead the OIC team forward in its mission, though I will continue to support OIC from afar. For the hundreds and thousands of lives OIC hopes to change for the better, the battle has barely begun. The organisation is almost four years old now, and while my team members and I have made some progress, there is still a long way ahead in terms of making speech therapy more widely available throughout Cambodia. OIC’s immediate tasks at hand are to get more schools, universities and workplaces to sign up for Day Without Speech, and to recruit more volunteers8 in Cambodia, or remotely. We also cannot do without the regular support of donors. 9

When I was majoring in international development at university, I assumed that change was created through large organisations, such as via decisions made in Washington or Geneva. However, my experiences have showed me that change will only, and has only ever happened, through individuals—ordinary people willing to make a stand to help others. Whether it is for Roger, in suburban Sydney, or Ling in rural Cambodia, it is up to us to make sure every child is given the start they need to flourish. If my time at OIC Cambodia has taught me anything, it is that real change begins with you.

Notes

1 CABDICO website, at http://cabdico.org

2 Weh Yeoh, Speech Therapy: Situational Analysis: Cambodia 2013 (Phnom Penh: Australian Red Cross and CABDICO, 2013), at http://cabdico.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Situational-Analysis-English-1.pdf

3 OIC website, at http://www.oiccambodia.org

4 Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2016–17 Edition, Speech-Language Pathologists, at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/ speech-language-pathologists.htm

5 Sebastian Strangio, Hun Sen’s Cambodia (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), at https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/21945075-hun-sen-s-cambodia

6 Day Without Speech website, at http://www.daywithoutspeech.org

7 Happy Kids Clinic website, at http://happykidsclinicpp.com

8 OIC Careers page at http://www.oiccambodia.org/careers

9 Find out how you can support OIC at http://www.oiccambodia.org/donate

|

Weh Yeoh is the founder and Managing Director of OIC Cambodia, a project that aims to establish speech therapy as a profession in Cambodia. He holds both a BA in Physiotherapy from the University of Sydney and an MA in Development Studies from the University of NSW. He has volunteered with people with disabilities in Vietnam, interned in India, studied Mandarin in Beijing, and milked yaks in Mongolia. Weh started OIC in 2013, and is now pleased to have four staff and over 30 volunteers on his team, all working towards making speech therapy accessible to the one in 25 Cambodians who need it. Weh can be reached at weh@oiccambodia.org |

Comments