By Jayal Shroff

I first decided to embark on a sustainable lifestyle while researching for a project on sustainability for my MA Design course. Its findings prompted me to reflect more deeply on the issue and reexamine the role of the individual in effecting systems change.

Image via Unsplash.

In Copenhagen, citizens generally prefer to cycle to their destinations. This preference has spurred the Danish government to invest around US$300 million dollars in their bicycling system to make it the easiest way to get around in the city. Over in Sweden, the “recycling revolution” started by the Swedish people has encouraged its government to develop a state-of-the-art waste collection system. Similarly in Seoul, traditional sharing markets—which see up to five million citizens participating and trading in a diverse variety of recycled or upcycled goods—have received huge support from the South Korean government. Let's not forget Italy’s Slow Food movement, which was born out of its people’s commitment to buy only local food; the movement has not only safeguarded the livelihoods of local farmers and small businesses, but also benefitted the health of the populace.

![]()

Image via rawpixel.

Studying such examples, we can see that such social innovations in sustainability are typically initiated by the citizenry instead of governments. These improvements—not necessarily technological ones—become possible when we can tweak traditional sustainable practices to be relevant in today's context, and in the process encourage more people to embrace behaviours and habits from 20 to 30 years ago.

Looking back, I realise that my education in sustainability started way before I began to think about it consciously.

Growing up in Mumbai during the 1980s, my family members and I would never discard items on a whim: I remember us gathering our old clothes and swapping them for steel vessels—or collecting newspapers, books, leaky metal taps, broken wooden stools and glass bottles, and exchanging them for cash at the paper mart or the scrap thrift store. Neither did we generate much waste. Whether it was a special occasion or a regular day, that tiny rubbish bin in the kitchen—the only one in the whole house—never overflowed. It typically contained only a few small bits of foil or paper, apart from kitchen waste.

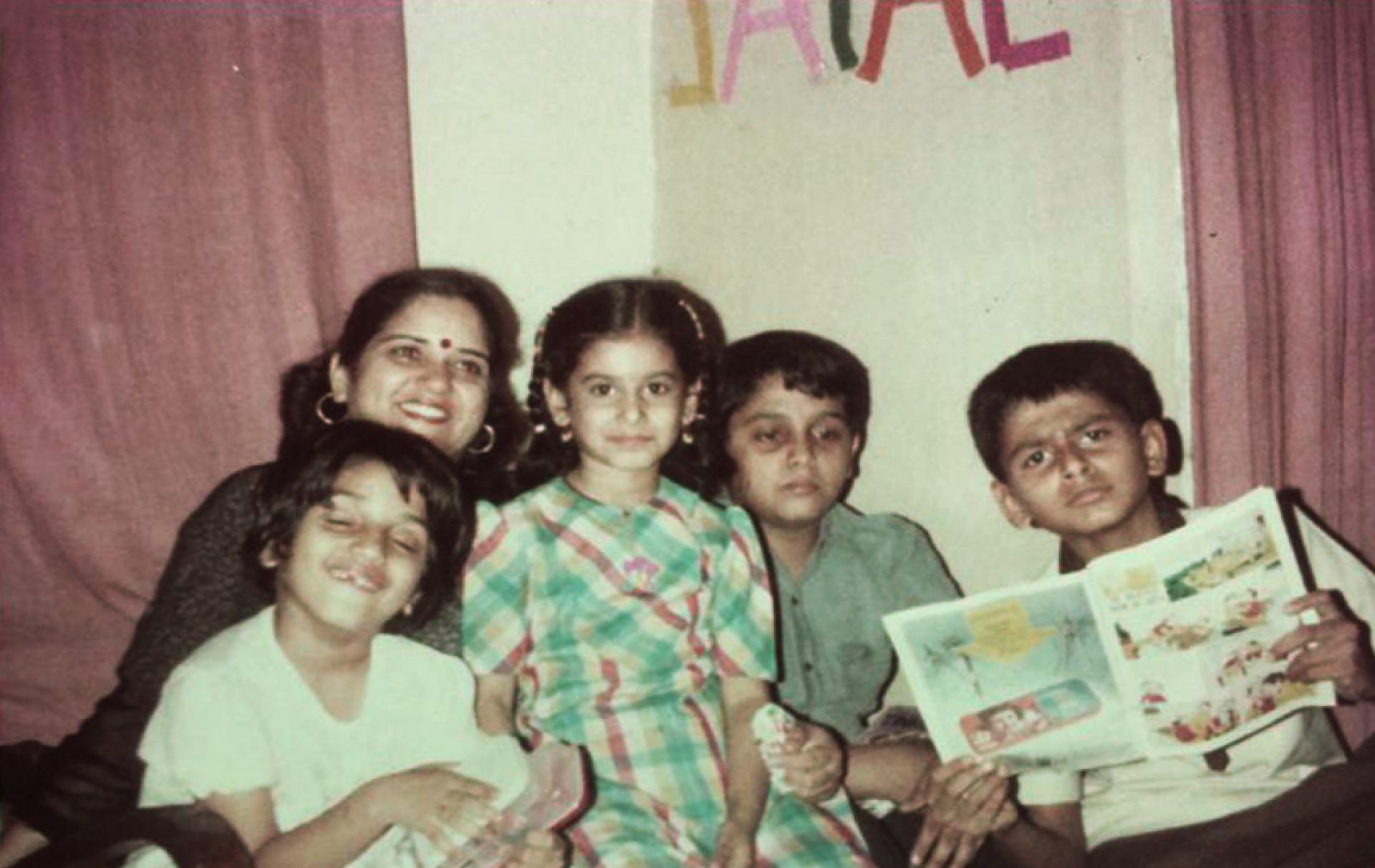

Jayal and her family celebrating her fifth birthday. "My mum made the food for everyone and the decorations were pretty simple." Image courtesy of the author.

Moreover, purchases were not made lightly. I owned precisely four pairs of footwear: two pairs of school shoes, a pair of slippers and another pair of "party" sandals. My toys were kept in a small 1.5 ft x 3 ft cupboard containing a few board games, a pack of cards, a doll, a couple of rubber balls and some Lego bricks, while my clothes occupied one shelf of a cupboard. We bought new appliances only when the present ones were utterly unfixable, or on special occasions like birthdays or Diwali. My family's practices were commonplace in many Gujarati households in India, even in the more affluent homes.

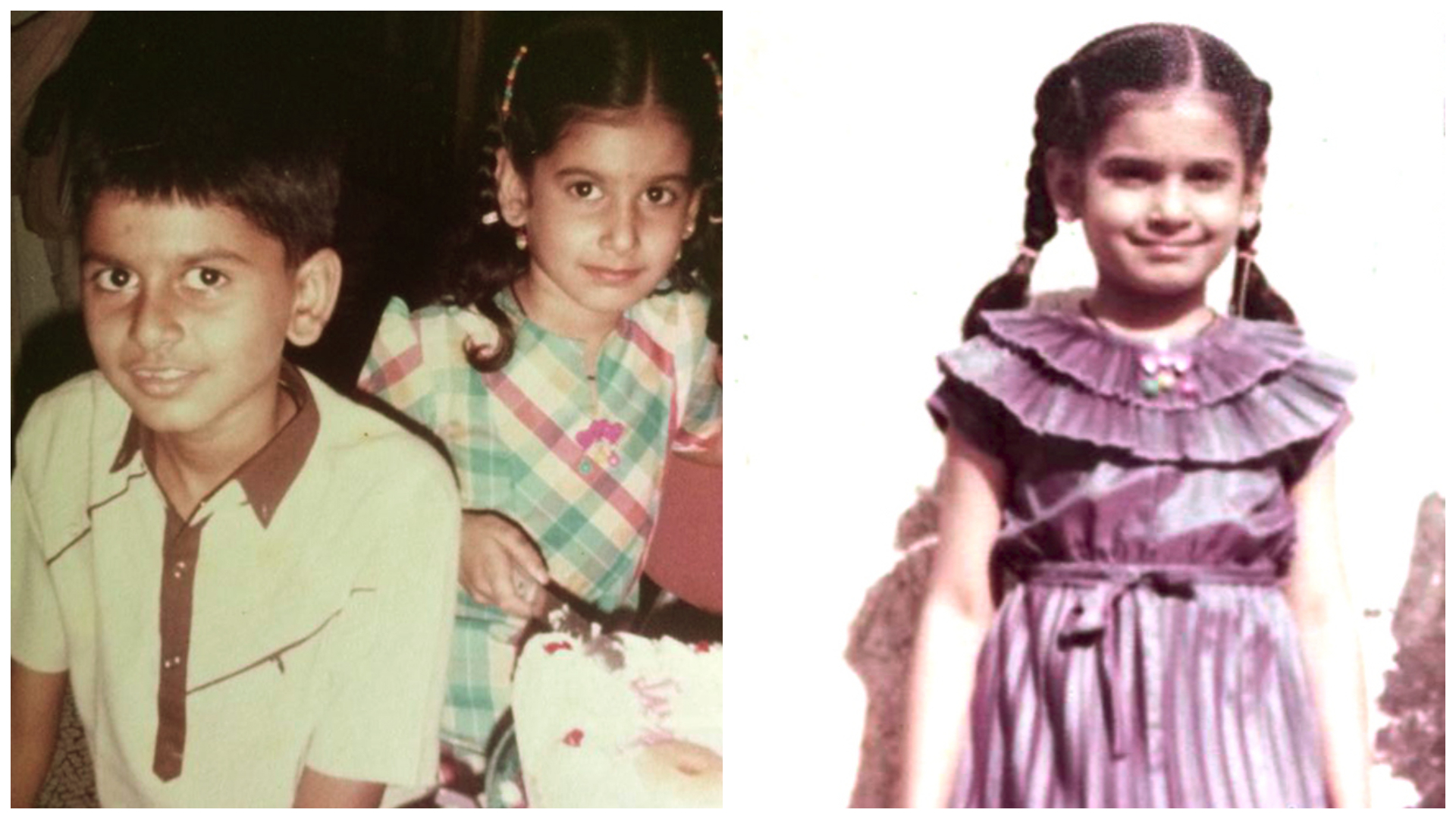

(Left) Jayal and her older brother at her fifth birthday party. Image courtesy of the author. (Right) A childhood picture of Jayal wearing her favourite dress. "I loved it so much I wore it till it was too short for me. Eventually, the dress was passed on to my younger cousin." Image courtesy of the author.

Back then, the cultural and societal systems supported a lifestyle that not only helped people to save money, but was also sustainable. For instance, it was acceptable to celebrate birthdays at home. It was customary to get a refund for returning glass bottles that our soft drinks came in. It was also the norm to get things fixed by cobblers and tailors, who were present almost on every other street. Carrying a reusable bag was another no-brainer when one went shopping. Even though the underlying motivation of these habits and behaviours was to save money, it inadvertently led to systems that were largely sustainable.

Sustainability Myths...Busted!

MYTH #1: Sustainability is the sole responsibility of the government. FACT: Governments cannot form societal and cultural systems. They may try to provide tools to push environmentally friendly systems, but these will not work unless the citizens come together and utilise them effectively.

MYTH #2: Establishing systems requires massive funding. FACT: Systems emerge from what is socially acceptable, and does not require any funding. Once the systems become the norm, the economy itself turns around to support them naturally.

MYTH #3: Individuals cannot make a difference to the environment. FACT: Movements emerge slowly, and the initial phases of change may not be immediately evident, but individual preferences and demands become cultural norms. These ultimately result in accepted systems within which a society starts to function.

Image via Unsplash.

Fast forward to today, my upbringing and education in sustainability shines through in some aspects of my life, but falls short in others. The following examples show how I swing between some long-established habits of the past and today's socially accepted way of life.

While I have a house full of electrical appliances and utensils that are 35 to 40 years old, I recently discarded a fully working refrigerator, just because we "really" needed a bigger one. When I host birthday parties for my daughter, I am also guilty of using reusable cutlery and decorating with many balloons. On the other hand, I am more conscientious when it comes to food wastage: I cook just enough for family meals to prevent having leftovers, and during grocery shopping I don't overbuy fresh produce in case they go bad in my (now bigger) fridge. My other efforts at being sustainable include opting for public transportation over driving to reduce my carbon footprint.

(Left) Jayal's 35-year-old waffle-maker: "This waffle-maker makes better waffles than any newer model we've had in our extended family. My husband has repaired it several times. The handle has also broken off and has been replaced by a wooden knob." (Middle) Jayal's 40-year-old blender: "This blender is old, but has not needed any repairs; just replacement of the plug and the rubber rings." (Right, top) Jayal's stock of paper bags: "We use them often to carry door gifts. Sturdier ones (from Decathlon or IKEA) are good for grocery shopping." (Right, middle) Jayal's repurposed cushion cover: "My mother-in-law repurposed these old and faded cushion covers into a covering for the printer at home." (Right, bottom) Jayal's used wrapping paper: "I usually ask my daughter to carefully open her presents so we can reuse some of the nicer wrapping paper."

Simple habits of the past to incorporate with the present

- Save and reuse miscellaneous items like party decorations, wrapping paper, shoeboxes, mailing envelopes and plastic/paper bags.

- Increase the longevity of clothes, phones, furniture and appliances by choosing to repair them before discarding them.

- Reserve shopping for special occasions.

- Swap, share or give away decluttered clothes, accessories, gadgets, books and toys.

- Carry one bag and one drink bottle everywhere you go.

- Use cloth napkins instead of paper napkins.

As systems have evolved over time, so have our behaviours and perceptions concerning sustainability. Today, due to ambiguity surrounding how individual actions impact the environment, many people operate under "acceptable" norms and seldom take their sustainability efforts beyond "what's usually done", "convenient" or "affordable". Some others chose to blame the "system" or wait for "things to change".

Image via Unsplash.

However, I strongly believe ordinary people are the ones who hold the power to effect change from the ground up. Knowing there are many others like me who are committed to more sustainable ways of living, I press on in my efforts.

I also hope this article encourages readers to learn and apply from the past, so we can collectively nudge societies towards a greater culture for sustainability.

Banner image via rawpixel.

|

Jayal Shroff is a design professional with a background in behavioural science. In a career spanning two decades, she has worked for several large brand-name corporations in India and around the world. With a keen interest in social impact work, Jayal has been involved in projects relating to safety, health and finance in the social space. For one such project, she received accolades for designing interventions that protect hundreds of people who trespass the railway tracks of Mumbai. With her present focus on sustainability, Jayal hopes to integrate her design knowledge with pre-existing and widespread theories as she pursues her MA course in Design at LASALLE College of Arts. She can be reached at jayalshroffsg@gmail.com |

Comments