By Sujith Kumar Prankumar

Much has been written on social media and how it has positively revolutionised communication and information transmission. The influence of social media is indubitable—it reaches anyone with an Internet connection, no matter their geographic location or socioeconomic status. This means information that was previously out of reach for isolated and less well-off communities is now accessible by more people than ever before. For example, University College London’s “Why We Post” social media anthropology project—conducted by nine researchers in nine different communities over 15 months—found that communities that have traditionally received comparatively lower levels of schooling now have access to unprecedented amounts of information that allow them to improve their literacy and to receive informal education.1

The democratisation of media has given rise to new occupations, such as YouTubers, digital marketers and bloggers, who—with some basic social media literacy—can enjoy viable and lucrative careers. For example, Felix Avrid Ulf Kjellberg, a 27-year-old Swedish video gamer with nearly 53 million subscribers on his YouTube channel “PewDiePie”, made more than US$15 million in 2016.2

However, social media does have its dark side in an increasingly volatile and uncertain world. With the power of publication shifting dramatically from professionals to consumers, there is an inevitable uptick in the production and dissemination of information of dubious origin and whose authors harbour questionable intentions. Increasingly, social media channels are under attack for contributing significantly to the “post-truth” era, a term that has been so widely discussed and debated that Oxford Dictionaries made it 2016’s “Word of the Year”, and defined it as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion or personal belief”. 3

Consumers can now select from innumerable media courses, and tend to engage with news and content that connect with their own convictions. Additionally, social media platforms such as Google and Facebook feed users personalised information based on data mined from each user, thereby creating “filter bubbles” that shield users from having to interact with contesting ideas. 4 Besides the filters and “customised” content, news feeds from some social media outlets—including Buzzfeed, Distractify and Upworthy—have also been criticised for relying on “clickbait” or sensational headlines to promote social media sharing, rather than direct page visits, in order to reach a wider audience. All these have made assessing the veracity of what is published online more difficult, and contributed to information pollution, or what child empowerment advocate and Ashoka Fellow Dr. Yuhyun Park calls “infollution”5 —which encompasses “addiction to violent computer games, cyber-bullying, sexual predators, obscenity and racism”.6

As all media is arguably becoming social, producers and consumers need to be literate in social media tools in order to make sense of what they are engaging in, and to exploit the full potential of social media networks. Social media engagement can assist social enterprises, social sector organisations and non-profits in developing partnerships and in spreading their respective messages. It humanises organisations and their causes by making them more “accessible” and meaningful. Youth, and millennials in particular, are highly connected, technologically empowered and social justice oriented, and it is critical that organisations hoping to engage these demographics create strategic social media plans that are engaging (if not entertaining), have a clear message and express a clear call to action.

Fortunately, there are many examples of organisations and campaigns that have successfully employed social media to engage and empower youth, as discussed in the next section.

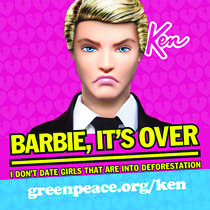

Three campaigns were particularly successful in engaging youth on social media: Greenpeace’s “Barbie, It’s Over”; the ALS Association’s “Ice Bucket Challenge”; and the Children's Cancer Foundation’s “Hair for Hope”.

These movements had the following in common: a strong social media strategy, a clear purpose linked to social responsibility and clear calls to action. In addition, they made it easy for anyone to take part (e.g. conveniently via mobile), the participation process was fun, and participants were able to share the campaign with others in a way that made them look and feel good about themselves. The first two campaigns, which featured extensive use of videos on social media, also managed to capture a larger audience, thereby suggesting that videos are one of the more effective means of capturing millennials’ attention.7

Greenpeace’s “Barbie, It’s Over” campaign is an exemplar of a story-based initiative involving a highly recognised and well-loved character. Greenpeace, a global non-governmental charity that champions environmental issues, wanted to pressure toymaker Mattel into dropping Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) from its list of packaging suppliers due to deforestation concerns. Launched globally in June 2011 worldwide and in nearly 20 different languages, the campaign featured a short film of a visibly distressed Ken dumping Barbie after watching a video of her secretly killing Sumatran tigers in Indonesian rainforests. The campaign also included a microsite, as well as Facebook and Twitter pages made to look as if authored by Ken, containing gossip on the break-up drama. The video clip’s tagline, I don’t date girls who are into deforestation, has nearly two million views on YouTube. 8

Instead of urging a boycott, the campaign focused on getting the audience to “unlike” Barbie’s Facebook page and to contact Mattel to ask them to cut ties with APP. By October that year, after temporarily shutting down comments on its Barbie Facebook page, Mattel released a statement on its commitment to not use products from controversial sources throughout its supply chain. Greenpeace further used the opportunity to highlight other major corporations committed to using sustainable sources of paper, in order to incentivise other organisations to do the same.9

The ALS Association’s “Ice Bucket Challenge” took a different approach. Instead of telling a story, it focused on inviting participants to challenge their friends. In 2014, the Association wanted to fundraise and raise awareness around Lou Gehrig’s disease, and got behind the idea of getting people to film themselves dunking a bucketful of iced water over their heads. After this, participants could nominate their friends and family to participate or donate to the Association, and these videos were shared on social media.

The campaign went viral worldwide with high participation among millennials and made more than US$100 million in donations over eight weeks. The reason for its success was not only the “fun” factor or that many celebrities took part, but mostly because people could easily make donations, such as via cell phones.10

In 2016, thanks to the donations from the “Ice Bucket Challenge”, a project team funded by the ALS Association made a “significant gene discovery”. 11

The Singapore-based Children’s Cancer Foundation’s “Hair for Hope” campaign takes a more straightforward and traditional approach. In this annual initiative, individuals, groups and organisations volunteer to get their heads shaved and then collect donations in solidarity for childhood cancer. The campaign is typically held in the middle of the year, and participants, called “Shavees”, upload pictures of themselves on social media to both show off their new “hairdo”, as well as to spread awareness of childhood cancer and seek donations. In 2016, donations totalled nearly S$3.35 million, up from about S$1.5 million in 2010.12

The campaign’s successful ability to unite donors and participants for a common cause can be attributed to the personal nature of cancer (no one is immune, and most people know of someone with cancer), as well as the high visibility of participants made possible via social media sharing—while “Hair for Hope” is not strictly a social media campaign, it is mobilised by youth who share pictures of their shaved heads on Instagram and Facebook and encourage others to participate or donate.

SOCIAL MEDIA CAMPAIGN TIPS

|

Campaigns and organisations need to go beyond creating interesting and sharable content; they should also empower consumers by providing ways to share, participate and invite others. The more consumers have to talk about—and interact—with an organisation, the wider the reach and the deeper the impact. 13

Social media, with all its challenges, presents tremendous opportunities to engage with people and issues from all over the world, not just for entertainment or employment, but also to learn about, organise, and take action on social issues.

Notes

1 Juliano Spyer, Shriram Venkatraman and Xunyuan Wang, How the World Changed Social Media (London: UCL Press, 2016), at http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1474805/1/How-the-World-ChangedSocial-Media.pdf

2 Madeline Berg, “The Highest-Paid YouTube Stars 2016: PewDiePie Remains No. 1 With $15 Million”, Forbes, 5 December 2016, at http://www.forbes.com/sites/maddieberg/2016/12/05/the-highestpaid-youtube-stars-2016-pewdiepie-remains-no-1-with-15-million/#3be341a56b0f

3 Oxford Dictionaries, “Word of the Year 2016 is …”, at https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-theyear-2016

4 Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web is Changing What We Read and How We Think (London: Penguin Press, 2011).

5 Dr Yuhyun Park’s profile at https://www.ashoka.org/en/fellow/yuhyun-park

6 Colin Power, The Power of Education: Education for All, Development, Globalisation and UNESCO (London: Springer, 2015).

7 Rachel Wolfson, “4 Ways Organizations Use Social Media to Engage With Millennial Donors”, Huffington Post, 16 June 2016, at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rachel-wolfson/4-waysYOUTH AND SOCIAL MEDIA organizations-use-social-media-to-engage-with-millennialdonors_b_10447884.html; Kathleen Kelly Janus, “Three More Ways to Engage Millennial Donors”, Stanford Social Innovation Review, 14 August 2014, at https://ssir.org/articles/entry/three_more_ways_to_engage_millennial_donors

8 Greenpeace, “Barbie's Rainforest Destruction Habit REVEALED!”, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Txa-XcrVpvQ&t=4s

9 Laura Kenyon, “Success: Barbie and Mattel Drop Deforestation!”, Greenpeace, 5 October 2011, at http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/news/Blogs/makingwaves/success-barbie-andmattel-drop-deforestation/blog/37176/

10 James Surowieki, “What Happened to the Ice Bucket Challenge?”, New Yorker, 25 July 2016, at http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/07/25/als-and-the-ice-bucket-challenge

11 The ALS Association, “ALS Ice Bucket Challenge Donations Lead to Significant Gene Discovery”, 25 July 2016, at http://www.alsa.org/news/media/press-releases/significant-gene-discovery-072516.html

12 Hair for Hope, “Hair for Hope, Make a Bald Statement”, at https://www.hairforhope.org.sg/page/Hair%2Bfor%2BHope

13 Kari Dunn Saratovsky and Derrick Feldman, Cause for Change: The Why and How of Nonprofit Millennial Engagement (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, a Wiley imprint, 2013).

|

Sujith Kumar Prankumar was Assistant Manager at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation. He studied communications at the University of South Australia, human rights at Columbia University, gender and religion at Harvard University, Modern Chinese at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and was a Kathryn Davis Fellow for Peace at Middlebury College. Sujith has worked in the media, higher education and inclusion sectors. A keen writer and top performer in Columbia Journalism School’s News Editing course, Sujith has contributed to various print and online publications. He can be reached at sujith.kumar@student.unsw.edu.au |

Comments